Pastors who qualify for a COVID-19 vaccine based on their involvement in medical settings or their role as essential workers hope that getting the shot will allow them to minister to the most vulnerable in person again.

But those who fall outside the typical qualifications for immunization—who are healthy, under 65, and not caretakers—also feel some apprehension over taking their place in line during a time when demand for vaccines still outpaces supply.

When Nathan Hart learned that, as a pastor who makes hospital visits, he was eligible to receive the coronavirus vaccine in Connecticut, he hesitated. It’s not that the senior pastor of Stanwich Congregational Church doubted the safety or efficacy of the vaccine, but as a healthy 42-year-old, he worried that he was taking the place of someone who might need the dose more than he does.

But then Hart remembered God’s words about Adam in Genesis 2:18: “It is not good for man to be alone.” He thought about the shut-ins from his church who had gone an entire year without a pastoral visit, or perhaps any visit at all.

“Members of my congregation have gone through hospital stays without a visit from their pastor,” he said. And though nurses and hospital chaplains have stepped up to offer emotional support for patients, he said, “their souls aren’t getting the medicine they need.”

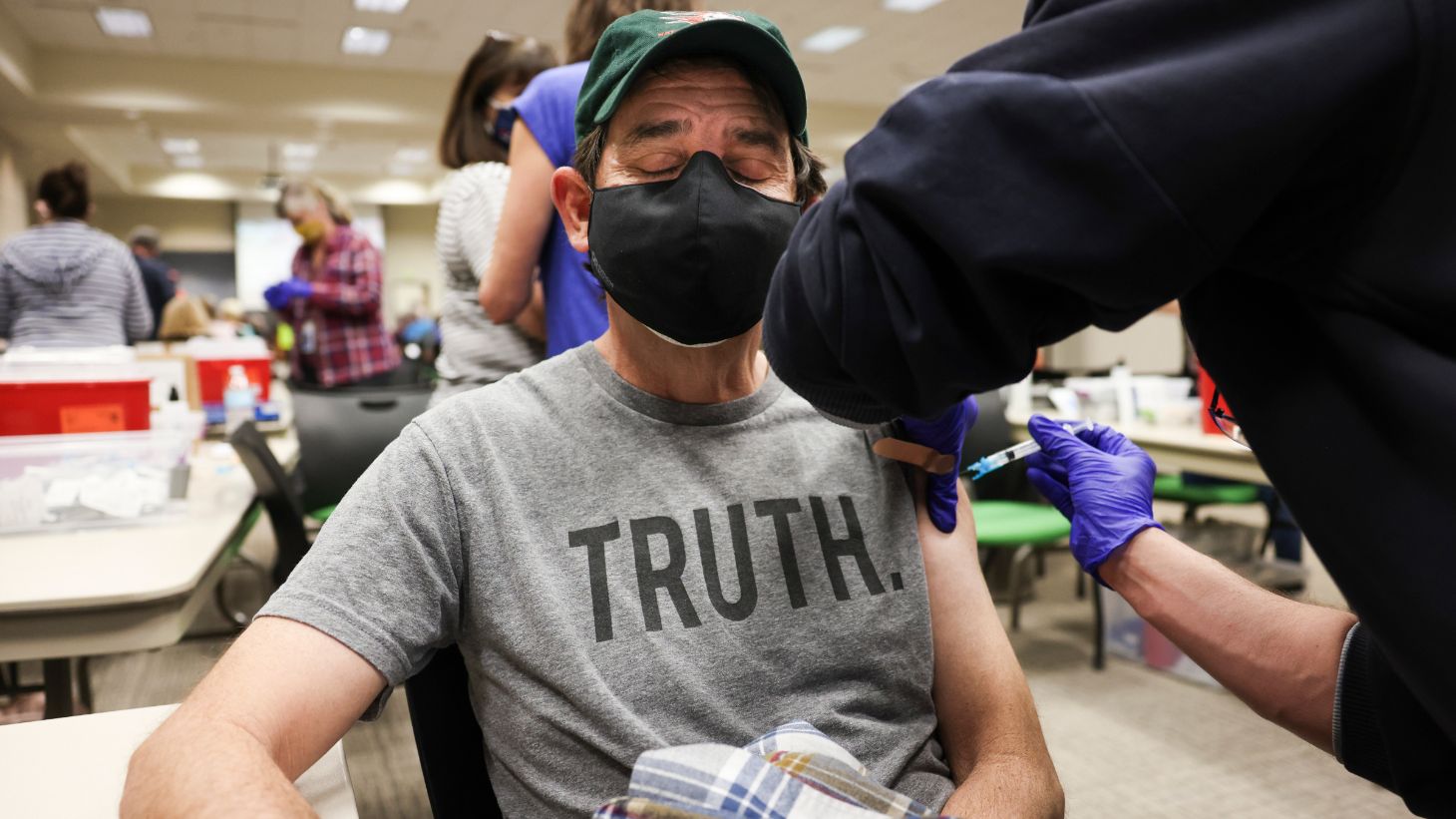

So Hart took his place in line to get vaccinated.

Many younger pastors who have gotten the shot already were eligible the same way Hart was: through provisions for those who work, even as visitors, in hospitals, hospices, nursing homes, or other medical facilities.

But some states—including Pennsylvania, Kentucky, North Carolina, New Jersey, and Virginia—explicitly designate clergy among their lists of essential workers, usually eligible in phase B. At least 18 states have named clergy or ministers in their vaccine plans.

Clergy and those who operate houses of worship are classified as essential personnel for vaccination by the US Department of Homeland Security Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, which suggests the guidelines for distribution plans used by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Because so many people could fit into the federal definitions of essential personnel, states inevitably have to narrow the lists and prioritize some occupations over others based on risk. Last week, New Jersey expanded its list to add clergy to the third round of phase 1B essential workers, alongside postal workers and judges. They’ll be able to get the get the COVID-19 vaccine beginning March 29.

There are some indicators that evangelical leaders as a whole may be more eager to get the vaccine than their congregants.

When the National Association of Evangelicals surveyed the 100 members of its board of directors, 95 percent said they would receive a COVID-19 vaccination when it becomes available to them. Respondents represent CEOs of denominations and representatives of a broad array of evangelical organizations including missions, universities, publishers, and churches.

White evangelicals and black Protestants are less likely than average Americans to say they plan to be vaccinated, according to Pew Research. As evangelicals question the science behind the vaccine, evangelical leaders, scientists, and ethicists have repeatedly tried to allay concerns in hopes those figures will change. (Overall, the share of Americans who say they would get the vaccine or have already is growing.)

When pastors roll up their sleeves for the vaccine, they also send the message to those in the pews (or over the screens) to trust the science above conspiracy theories. The CDC playbook encourages states to reach out to faith-based groups to “educate about vaccine recommendations and availability and to address hesitancy” as well as serving as vaccine clinic sites.

Though Arizona does not specify a place for clergy in its vaccine rollout plan, clergy in Pima County qualify for the vaccine under a provision for “traditional/faith healers.” Angel Haynes heard through a local ministry network that she was eligible for vaccination, and the women’s minister at Second Mile Church in Tucson signed up, along with her husband, the church’s senior pastor, and its two other ministers.

Practically speaking, having a vaccinated staff changes little for Second Mile Church. The pastors and staff still wear masks, and worship services are limited to 50 people. But Haynes feels that getting vaccinated shows solidarity with the health care workers and teachers in the congregation.

In a young congregation that doesn’t always take seriously the threat of COVID-19, Haynes believes getting vaccinated lets frontline workers know that the pastors see and value what they do. Plus, receiving the vaccine helps Haynes feel less exposed and better able to engage with the hurting without worrying about passing on the virus in the day-to-day work of ministry.

“If it gives pastors that relief, I think they should get it. If someone’s in need, we’re going to make sure we meet those needs,” she said.

Like Haynes, Jim Shellenberger discovered that he qualified to receive the COVID-19 vaccine when his county, Finney County, Kansas, issued differing guidelines from the state.

“While it helps to protect my own health as well, I feel like I have an obligation to also protect the well-being of my neighbor and the least of these,” said Shellenberger, an associate pastor at Garden Valley Church who researched the vaccine before signing up to get the shot last month.

He tweeted, “Vaccines are pro-life” after receiving his second dose last week.

That obligation to care well for others weighs heavy on pastors who minister among populations that are most at risk for serious cases of COVID-19 and most affected by the social restrictions.

Nearly half the members of Westfield Presbyterian Church in New Castle, Pennsylvania, are senior citizens, and over 40 live in long-term care facilities. Bobby Griffith moved from Oklahoma City to become its new senior pastor last August, just before a late-fall spike in cases in the rural Pennsylvania town.

Griffith noticed that residents in his new community treated him with a measure of respect because of his position as clergy, but they wanted a pastoral visit when they were in the hospital. When Pennsylvania began vaccinating essential personnel, Griffith discovered that because of his hospital visits, he did not need to wait until Phase 1B to get his vaccine.

Even being partially vaccinated has given Griffith access to the sick and lonely. After a recent visit to a hospitalized church member, he heard from hospital staff how lonely all of the patients were. When he told the staff that he was partially vaccinated, they said he was welcome to knock on any door in the hospital to visit patients.

Hart in Connecticut appreciated that the governor determined ministers play a vital role in caring for the sick and dying. And he can hardly wait to see again the members isolated by the pandemic.

“When I’m fully immune, I will be driving to the hospital and long-term care facilities to make those visits,” he said.

States That Name Clergy in Their Vaccine Rollout Plans

|

Alabama |

Phase 1B – “Ministers/clergy” fall under “frontline critical workers” |

| Colorado | Phase 1B.4 – “Faith leaders” listed among workers who work in close contact with many people |

|

Idaho |

Current eligible groups – “Clergy who enter healthcare facilities to provide religious support to patients” |

| Illinois |

Phase 1A – “Clergy/Pastoral/Chaplains” in hospital settings |

| Indiana |

Current eligible groups – “Clergy who see patients in a healthcare setting” |

| Kentucky | Phase 1C – Clergy listed among “other essential workers” beyond the frontline |

| Massachusetts |

Phase 1 – “Members of the clergy (if working in patient-facing roles)” listed among health care workers doing non-COVID care |

| Maryland | Phase 1C – “Clergy and other essential support for houses of worship” |

| Missouri |

Phase 1A – Clarification lists “clergy who minister to those in long-term care facilities or hospitals” as eligible |

| New Hampshire |

Phase 1A – Clergy working in health care fall under “non-clinical frontline workers” |

| New Jersey |

Phase 1B – Clergy listed among “frontline essential workers” |

| North Carolina |

Group 3 – Clergy fall under essential workers providing “government and community services” |

| North Dakota |

Phase 1A – “Chaplain staff” at hospitals Phase 1C – Doesn’t explicitly name clergy but says “all other essential workers per Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency,” which lists clergy and essential support for houses of worship, are eligible if they cannot work form home |

| Pennsylvania | Phase 1B – “Clergy and other essential support for houses of worship” |

| Puerto Rico |

Phase 1C– “Clergy/spiritual assistance personnel” |

| South Dakota |

Phase 1C – Clergy in medical settings |

| Virginia |

Phase 1B – “Clergy/faith workers” listed among frontline essential workers |

| Wisconsin | Current eligible groups – “Spiritual care providers” in health care settings |

Note: Some counties use different guidelines than states. Contact your local health department to see if you qualify for a vaccine in your community.