Some of the rioters who stormed the US Capitol in early January chanted their demand to “hang Mike Pence.” But some likely thought the former vice president was already dead.

In fringier corners of former President Donald Trump’s base, particularly those influenced by the QAnon conspiracy theory, there’s a rumor that Pence was executed by a Trump-run military tribunal last year. So were the Obamas, the Clintons, President Joe Biden, and Chief Justice John Roberts. News reports showing them apparently reacting to current events, the story goes, are simply computer-generated. Or maybe holograms. Or actors? Or clones!

This is, of course, absurd. It’s also utterly unassailable: We can’t take Biden around for a doubting Thomas routine with every conspiracy theorist. Even if we could, there’s no external proof this sort of theory cannot account for and dismiss.

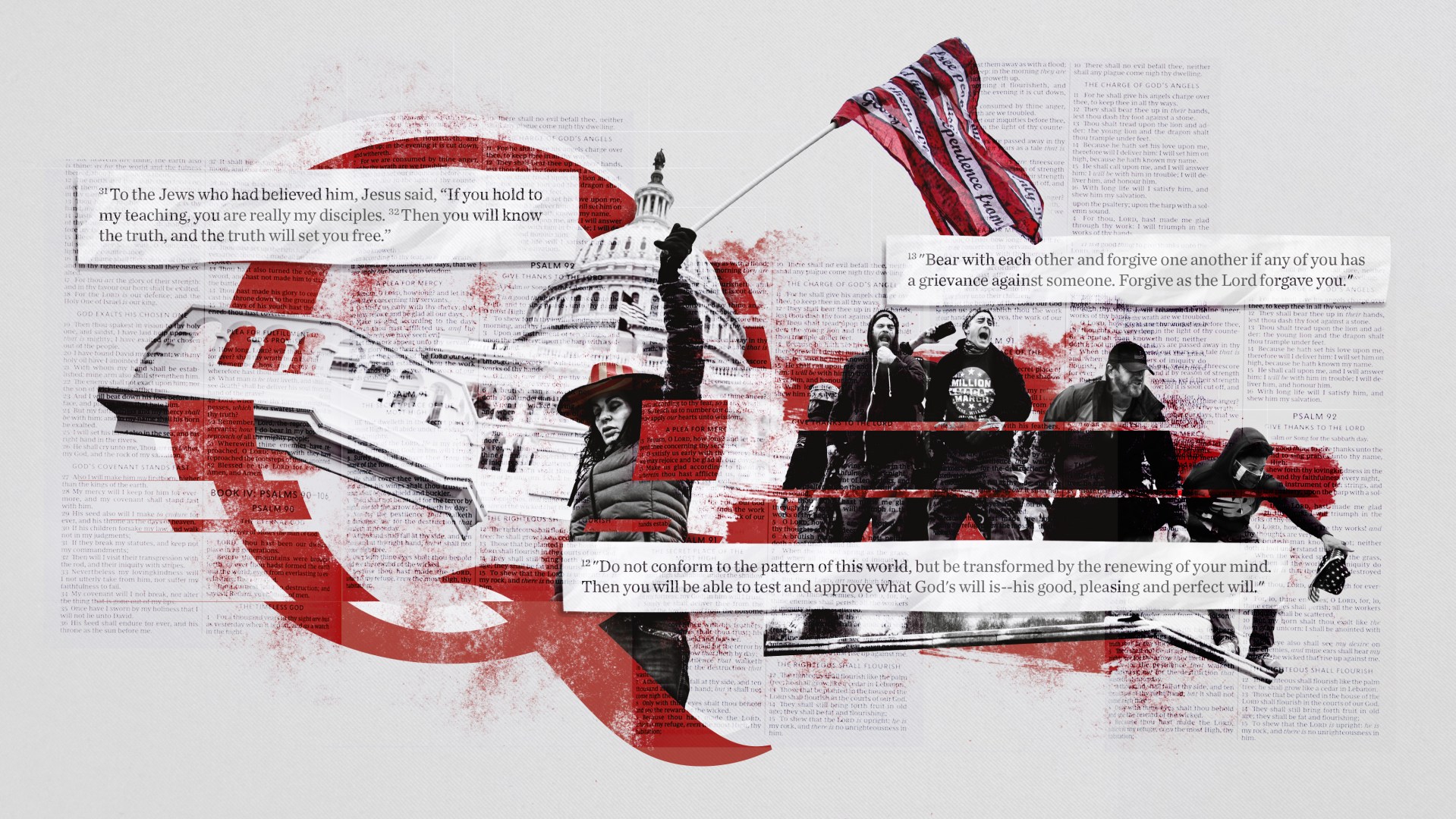

But most remarkable about this belief is that some significant portion of the people who hold it would describe themselves as evangelicals. Their social media bios are festooned with phrases like “conservative Christian,” “Bible-believing Christian,” “fighting for faith,” “John 3:16,” “God-fearing,” “Christian, wife, and mother.” They share Bible verses, sometimes in the same post as their conspiracy theorizing. They express faith that God will accomplish the overhaul of American governance of which the imagined executions are just one part. They might go to church—maybe your church.

Most politically engaged Americans generally, and Christians specifically, don’t believe anything quite so wild. But this theory about high profile executions is not quite the aberration we might hope. “[I]n my experience and in my conversations among pastors, we are growing more and more alarmed by the prevalence of belief in conspiracy theories and far-fetched political ideas, especially since the election,” said Daniel Darling, who is a pastor, the senior vice president of National Religious Broadcasters, a CT contributor, and author of books including A Way with Words: Using Our Online Conversations for Good.

Darling’s perspective, which he shared with me in an email interview in January, is backed up by new survey data from Lifeway. Fully half of Protestant pastors in America say they “frequently hear members of [their] congregation[s] repeating conspiracy theories they have heard about why something is happening in our country,” that poll found. The trend seems to be strongest, said Scott McConnell, executive director of Lifeway Research, “in politically conservative circles, which corresponds to the higher percentages in the churches led by white Protestant pastors.”

“With most pastors I talk to, it’s a fraction of their congregations,” Darling told me, “perhaps among the most politically engaged or the most plugged in online. And yet it is enough of an element that it has many pastors worried,” he continued, especially about “how captive many [Christians] are to their preferred media outlets, which are growing more and more extreme, and how seemingly resistant many are to hearing reasonable rebuttals.”

The effect is an epistemic crisis, and it is not exclusively a fringe phenomenon. The subtler lie can be the strongest—“If you think you are standing firm, be careful that you don’t fall!” (1 Cor. 10:12). This crisis is more than a pressing political problem; it’s also an urgent matter of Christian discipleship, for Christians are supposed to be people of truth (John 8:31–32).

Epistemology is simply the study of knowledge: What do we know and how do we know it? What are trustworthy sources of knowledge? Is the world really as we perceive it? If truth exists (as Christians affirm), can we access it rightly? We are in an epistemic crisis because our answers to these questions in the public sphere are a disastrous mess.

An epistemic smog is pouring into our homes and our heads via autoplay and infinite scroll.

The last five years of American politics have been a time of “alternative facts” and “truth [that] isn't truth.” Accusations of “fake news,” some fair and some cynically slanderous, fly fast and thick. Mainstream media outlets are rejected for being flawed or biased (an oft-deserved critique!), but the pseudonymous digital rumor-mongers rising to replace them are worse. Too many on the Right embrace “dreampolitik”—if it feels right, believe it—while among too many on the Left, a totalized emphasis on personal experience as a mediator of knowledge renders communication impossible across the lines of identity. The upshot is we’re certain about things that don’t warrant certainty and doubtful of basic facts. An epistemic smog is pouring into our homes and our heads via autoplay and infinite scroll.

I wanted to talk to Darling because I think I can describe this problem well. I certainly know it when I see it, including—to my dismay—in my own family. But I commonly feel at a loss as to what to do about it. I know what it looks like in my life to practice what Graeme Wood at The Atlantic called “mental hygiene” (which I would say is a spiritual hygiene, too). “The struggle is internal, and familiar to all who consume media,” Wood wrote, and for me it has meant limits—too often broken—on the time and content of my media consumption, as well as a daily routine that includes reading Scripture before my phone.

But what about other people, people who may not even recognize the epistemic crisis exists? I can’t impose my limits and routine on them. G. K. Chesterton in Orthodoxy advised against arguing with the conspiracy theorist, recommending instead to give him “air,” to show there is “something cleaner and cooler outside the suffocation of a single argument.” But what does that look like in the age of smartphones, when an endless font of controversy and confusion is always in our pocket?

Public commentary—like this very article—can only do so much, Darling told me. It serves “a purpose,” he wrote, “but this has to be solved relationally” and in the local church. Too “many evangelicals are catechized more by their favorite niche political podcast and pundits and politicians” than by the Bible, he continued, a characterization which I suspect might be unwelcome, but which is indisputable if we consider the time allotted to each.

“So perhaps pastors need to return to this kind of old-fashioned preaching that warns against bad influences and urges us to ‘renew our minds’ (Rom. 12:2) with Scripture,” Darling said, while including in their discipleship practices “a sustained and nuanced emphasis on what it means to engage politics in a healthy way.” Churches can use small groups, recommending reading, research, and podcasts, as well as classes to train and encourage members. To fail to address political engagement and content consumption, Darling argued, means “ceding that ground to the fear merchants and media conglomerates who trade eyeballs for profit.”

And all this must happen in the context of Christian love: in friendship; in prayer and fasting and spiritual warfare (Eph. 6:10–18); in “bear[ing] with each other and forgiv[ing] one another” (Col. 3:13). We may not be able to argue people out of epistemic crisis—but we can appeal, Darling concluded, to Christian virtue and mission, asking questions like: Is this really worth our time and energy? Does it help us “to live a life worthy of the calling [we] have received” (Eph. 4:1)? Does it turn anyone’s mind toward Christ? We needn’t believe in Clone Biden for the answer to be “no.”

Bonnie Kristian is a columnist at Christianity Today.