Ken Liu reads the Bible like an attorney. When Proverbs 31:9 says to “defend the rights of the poor and needy” and Psalm 82:3 says to “uphold the cause of the poor and oppressed,” he hears the Scriptures addressing lawyers like him.

“God really calls us attorneys specifically to serve the poor,” said Liu, director of Christian Legal Aid, a branch of the Christian Legal Society. “So many of the causes of poverty are legal issues…. In this country, lawyers have a monopoly on providing legal services. If we don’t help, no one else can.”

Liu is one of hundreds of lawyers in more than 60 clinics across the country who are motivated by their belief in Jesus and their understanding of the Bible to give their time and skill to minister in the justice system.

The clinics in the Christian Legal Aid network represent people who cannot afford market-rate legal representation, which averages $100–$400 per hour in the US. The Christian lawyers offer pro bono or “low bono” help, often with sliding-scale fees determined by what a client can afford.

Some of the clinics focus on helping immigrants and refugees. Vineyard Immigrant Counseling Service outside Columbus, Ohio, for example, focuses on defending people seeking asylum and immigrants who were brought to the US as children. Immigrant Hope, in Clifton, New Jersey, helps with naturalization, petitions, permanent resident card applications, and renewals, providing legal services in Spanish, Turkish, Arabic, Albanian, and Portuguese.

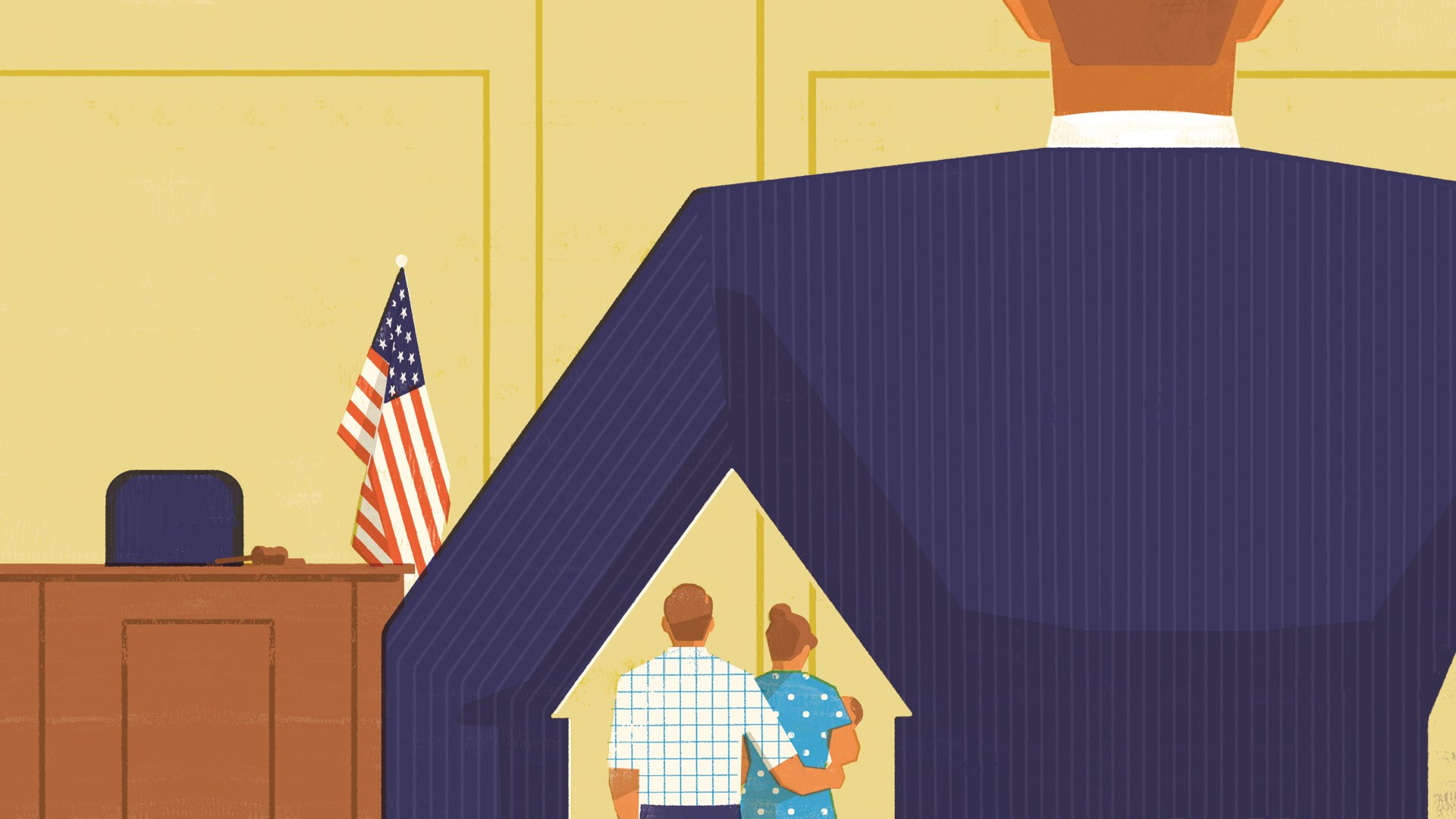

But the crisis that Christian legal aid clinics were bracing for at the start of 2021 was the eviction of poor people from their homes, as pandemic-related moratoriums protecting struggling renters started to disappear.

“COVID has taken an already-compromised situation for tenants and made it just untenable,” said Al Johnson, director of New Covenant Legal Services in St. Louis.

Since the start of the pandemic, a national eviction crisis has been held at bay by a patchwork of local, state, and federal measures protecting renters. Tenants who were behind on rent because of COVID-19 were allowed to stay in their homes—temporarily.

Experts predict as many as 12.4 million Americans could face eviction when the legal protections expire.

“It’s just a deteriorating situation,” Johnson said. “The minute those moratoriums are lifted, people are going to go out on the street.”

Even with the moratoriums in place, Johnson’s legal aid clinic has been busy throughout the pandemic, helping clients whose landlords misunderstood or ignored government orders. In St. Louis, they fought landlords who tried to start court-ordered evictions early, intimidated renters into leaving their homes, or simply locked out residents without warning. Some are already suing their tenants for back rent.

Most of the tenants cannot afford legal representation. St. Louis sees an average of about 50 people facing eviction every week, Johnson said, many unrepresented.

The legal help can make a huge difference. A 2001 study of New York City’s housing court found that 51 percent of unrepresented tenants lost their cases, while only 22 percent of represented tenants lost theirs.

In some civil cases, attorneys are not allowed to represent their clients; a pro bono lawyer can only make sure a client has properly filled out paperwork and knows as much as possible about the laws and technicalities that the judge will consider.

But all the coaching in the world can’t replace a law degree or courtroom experience, Johnson said. When attorneys are allowed to represent their clients in court, it’s only a fair fight if both sides have one.

Winning the court case is the goal, Liu said, but he hopes people find even more at Christian clinics. Many of the clients also need someone to talk to, maybe even pray with. Many are hurt and wounded in ways that a successful court case won’t fix.

“The legal problems are typically just the tip of the iceberg,” Liu said. “We see ourselves as the urgent care clinic down the street that sees people before they have to go to the hospital.”

When it’s time to go to court, the lawyers’ goal is to make sure that injustice is not heaped on top of clients’ mounting burdens.

Poor people face a lot of hurdles in the justice system, and the coronavirus has added more. Johnson said his clients, for example, now have to attend some court hearings over Zoom, and many don’t have the stable internet, quiet space, or technology to telecommute to court for a high-stakes hearing. One of his clients recently had to call into a Zoom meeting by phone from the car where she was living. Such circumstances are simply not conducive to fair outcomes, Johnson argued.

“This is where our mettle is being tested,” said Katina Werner, executive director of Christian Legal Collaborative Inc. in Sylvania, Ohio, near Toledo.

Werner recently found herself standing outside a hospital window to serve as a witness while her client signed documents inside. She had to get creative, she said, because the hospital was telling her that because of COVID-19 restrictions, the patient would have to sign without an attorney present to answer questions about the document.

While she understands the need to keep people safe from the virus, Werner said, those protocols cannot come at the expense of people’s legal rights. As a Christian and a lawyer, she has to find ways to protect people who are vulnerable to exploitation.

“Normal rules don’t apply [during COVID-19], but we have to do some problem solving,” she said.

As COVID-19 restrictions shift and change in response to the pandemic, vulnerable people are often forgotten or made more vulnerable. For Johnson, protecting clients like these is just what it means to follow Jesus. He says he knows many haven’t seen this kind of work as a priority for the church, but he hopes that will change.

He wants to see more Christians follow Jesus, who said in Luke 4:18, “The Spirit of the Lord is on me, because he has anointed me to proclaim good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim freedom for the prisoners and recovery of sight for the blind, to set the oppressed free.”

“If we’re looking for somewhere to serve,” Johnson said, justice for the poor “ought to be the first thing you do, not the last thing.”

For the hundreds of attorneys in Christian legal aid clinics, that means going to court.

Bekah McNeel is a Texas-based reporter.