“Consider it pure joy, my brothers and sisters, whenever you face trials of many kinds, because you know that the testing of your faith produces perseverance.”

James, the brother of Jesus, didn’t have a global pandemic in mind when he wrote these words in the opening chapter of his biblical epistle to “the 12 tribes scattered among the nations.” But as the coronavirus closed churches worldwide, a global survey of more than 14,000 people has found that few lost faith while many of the most faithful gained.

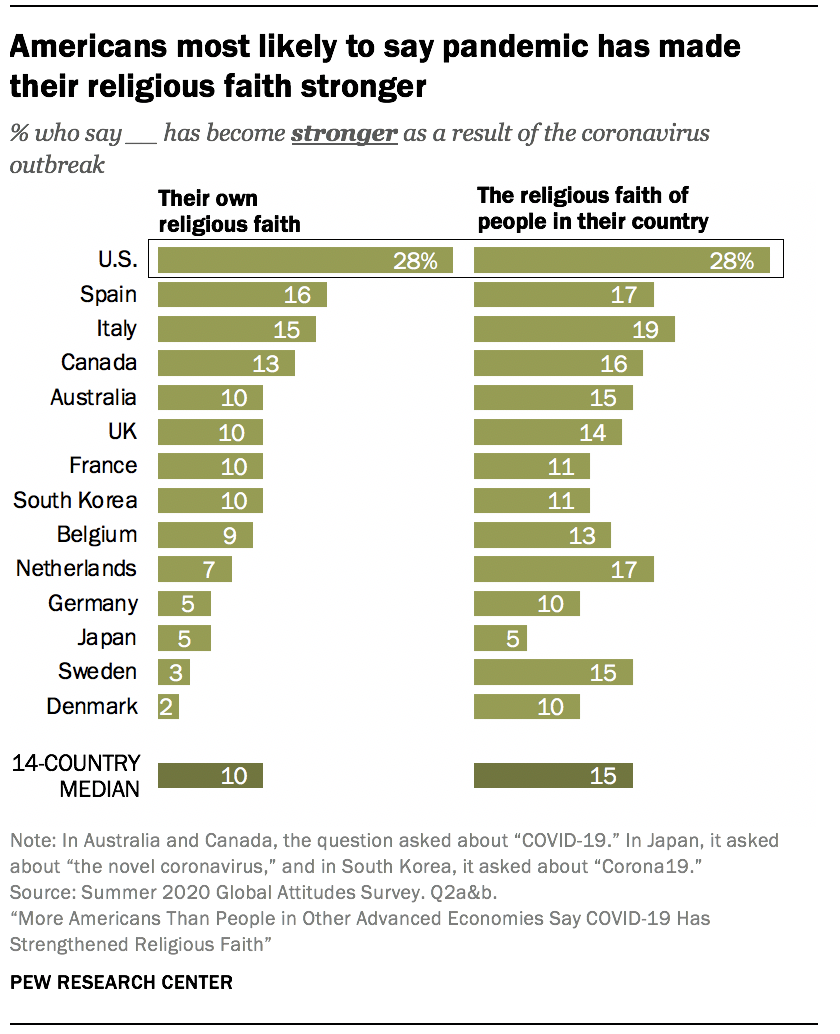

Today, the Pew Research Center released a study on how COVID-19 affected levels of religious faith this past summer in 14 countries with advanced economies: Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Spain, South Korea, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

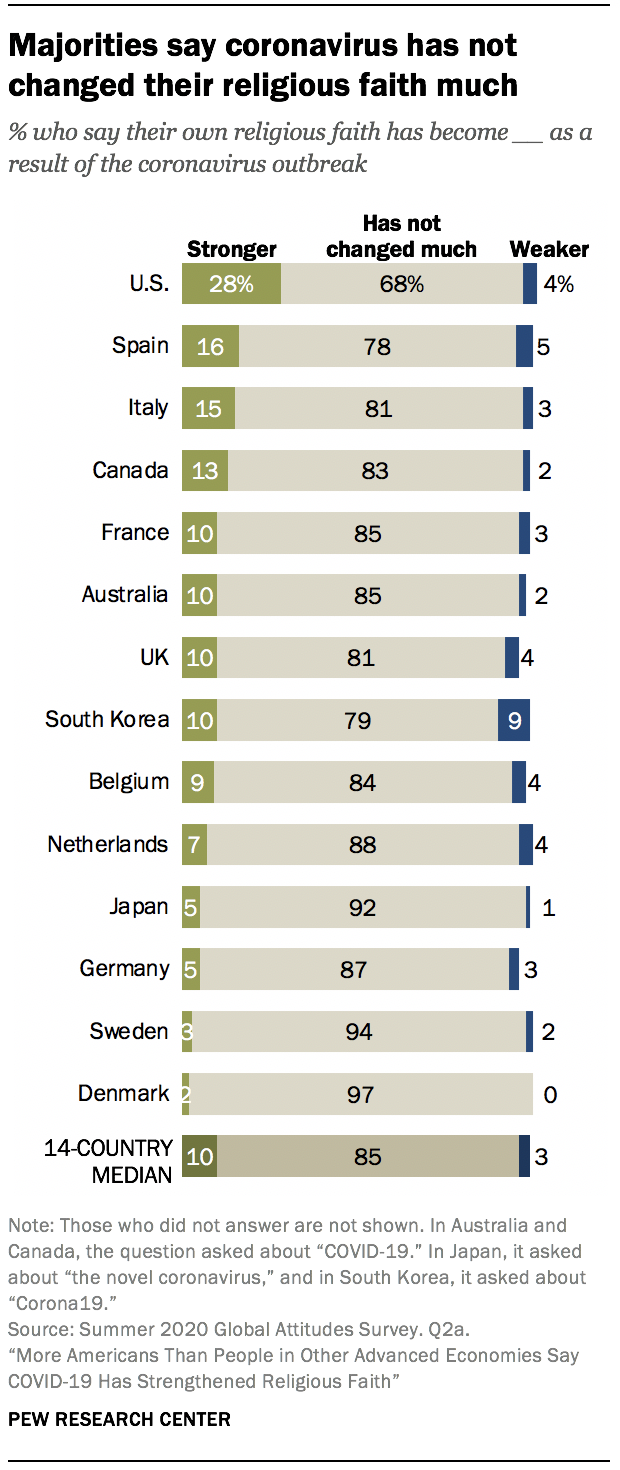

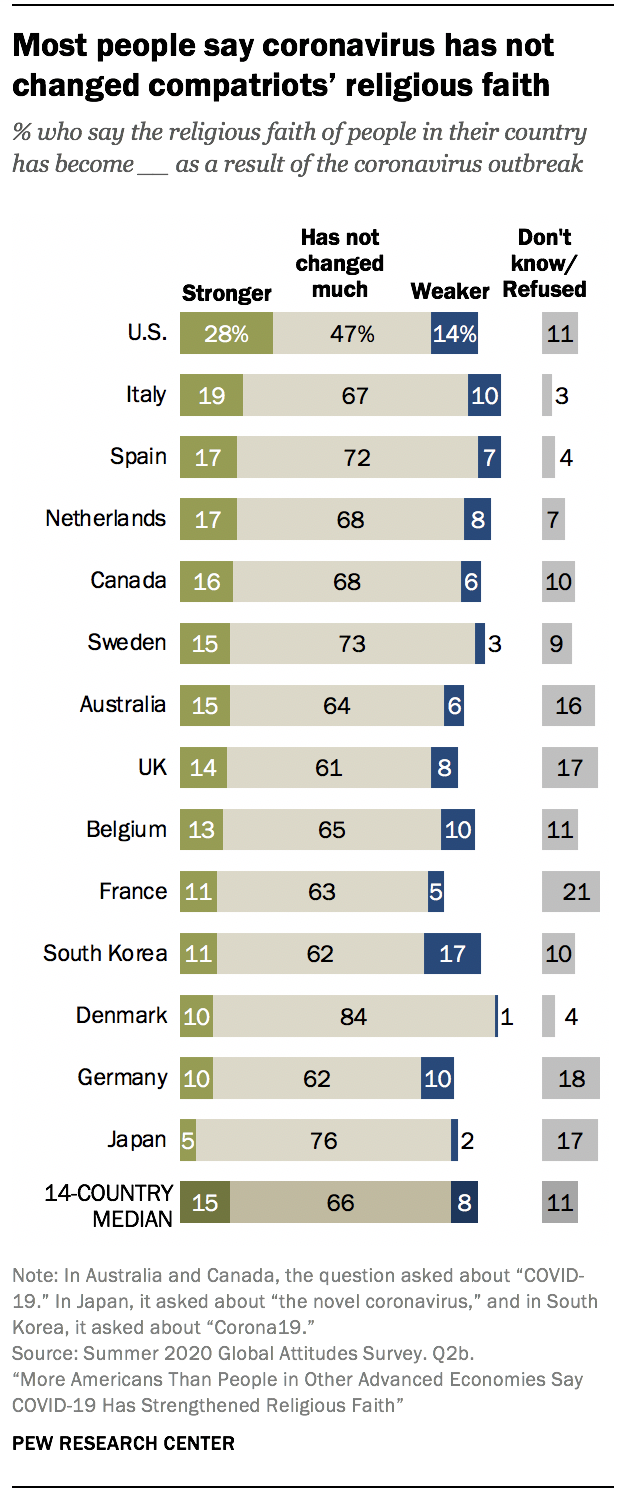

“In 11 of 14 countries surveyed, the share who say their religious faith has strengthened is higher than the share who say it has weakened,” noted Pew researchers. “But generally, people in developed countries don’t see much change in their own religious faith as a result of the pandemic.”

Overall, a median of 4 out of 5 of each country’s citizens said their faith was more or less unchanged.

But leading the pack in strengthened faith: the United States.

And leading the pack in weakened faith: South Korea.

Americans were three times more likely to report their religious faith had become stronger due to the pandemic: 28 percent, vs. a global median of 10 percent. Next came Spaniards (16%) and Italians (15%), whose nations were two of the worst hit during the coronavirus’s deadly outbreak in the spring. About 1 in 10 Canadians, French, Australians, Brits, Koreans, and Belgians said the same.

Meanwhile, Koreans were three times more likely to report their religious faith had become weaker due to the pandemic: 9 percent, vs. a global median of 3 percent. Next came Spaniards (5%), followed by a tie between Americans, Brits, Belgians, and the Dutch (4%).

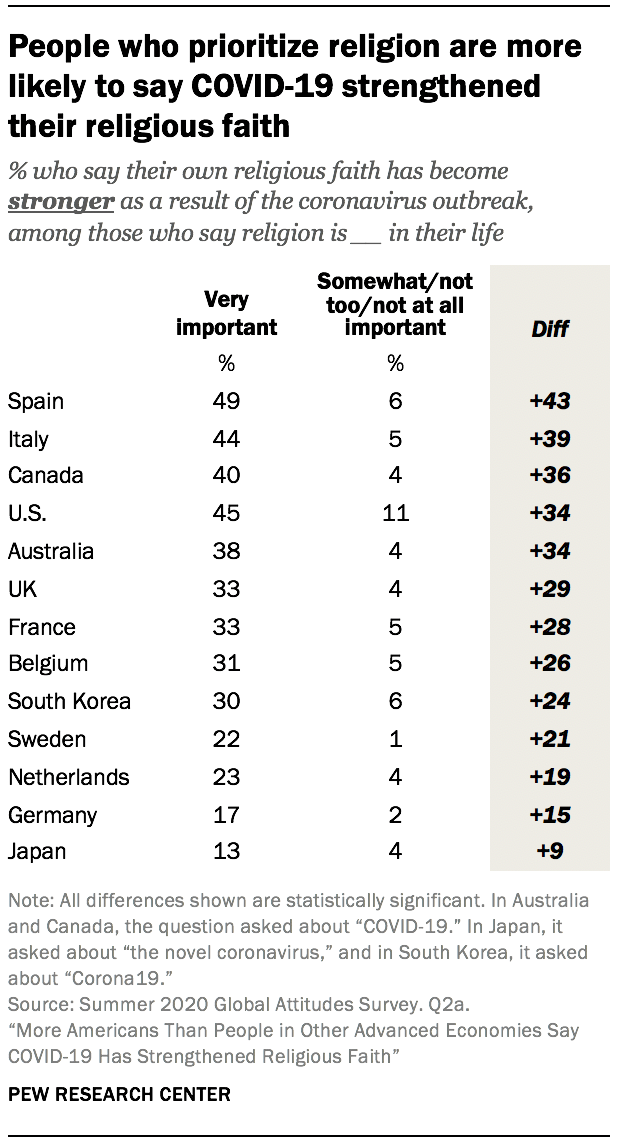

However, among only respondents who said religion was “very important” in their lives, a far larger share reported strengthened faith. This included 49 percent of faithful Spaniards, 45 percent of Americans, 44 percent of Italians, and 40 percent of Canadians. The global median was 33 percent.

Once again, South Korea reported the most lost faith. Among Koreans who said religion was “very important” in their lives, 14 percent said their faith had become weaker—about three times the global median of 5 percent. They were followed by the French (8%), Brits (7%), then a tie between Spaniards, Dutch, and Swedes (5%).

Among respondents who said religion was not important or only somewhat important in their lives, 1 in 10 Americans reported strengthened faith (11%), followed by Spaniards and Koreans (6%).

(The United States remains an outlier on religiosity: 49 percent of Americans told Pew that religion is very important in their lives, vs. 24 percent of Spaniards and 17 percent of Koreans.)

Pew found no significant differences between men and women overall, but “two exceptional cases” were Italy and South Korea. In Italy, 20 percent of women say their faith has strengthened vs. only 10 percent of men. In South Korea, 13 percent of women say their faith has strengthened vs. only 8 percent of men.

Pew also asked respondents to assess the pandemic’s impact on the faith of their nation as a whole. Once again, Americans led the way with 3 in 10 saying faith in the US had become stronger.

In most countries, people were more likely to say the religious faith of their fellow citizens had become stronger (global median: 15%) than to say the same about their own faith (global median: 10%). Significantly, in the Netherlands only 7 percent of the Dutch say their own faith is stronger, but 17 percent say the faith of other Dutch is stronger. The same significant spread was found among Swedes (3% vs. 15%) and Danes (2% vs. 10%).

Meanwhile, Koreans were most likely to say that religious faith in their nation has weakened (17%), followed by Americans (14%) then by Italians, Belgians, and Germans (10%). Others matched or fell below the global median (8%).

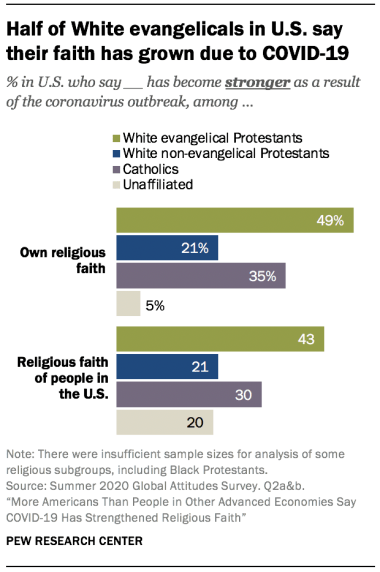

In the US, white evangelicals were the most likely to say their faith had become stronger (49%), followed by Catholics (35%), white non-evangelical Protestants (21%) and the unaffiliated (5%). This was a modest increase from April, when Pew found a strengthened faith reported by 41% of white evangelicals, 27% of Catholics, 19% of white non-evangelical Protestants, and 7% of the unaffiliated.

Pew’s summer survey did not have enough black Protestants to break out, but in the April survey they led all American faith groups, with 54 percent saying their faith had been strengthened.

After being cleared of mail fraud allegations, organizers of the “Religious Inaugural Celebration …” in Washington, D.C., proceeds on course with plans for this month’s interfaith prayer service that coincides with the change in administration.Charges of misleading the public were directed against James “Johnny” Johnson, who planned the gathering in his capacity as an independent, evangelical lay minister. (He serves as vice-president of the Full Gospel Business Men’s Fellowship, and was assistant secretary of the navy under Richard Nixon. Johnson also has close ties with the President-elect, who appointed him director of veteran’s affairs in California in 1967. He was the first black ever named to a state cabinet post.)In October, Johnson’s independent inaugural committee issued more than 40,000 formal invitations, which bore a gold, embossed eagle emblem. The official-looking invitations requested attendance at a “nonsectarian, nonpartisan, nonpolitical” prayer meeting on January 19 and 20 at Washington’s Starplex Armory. After the election, Ronald Reagan’s official inaugural committee complained that the invitations would confuse and mislead recipients by suggesting that purchasers of the tickets would be treated to an appearance by either Reagan or Vice-president-elect George Bush. In fact, neither one had agreed to attend the festivities, though both were invited.As a result, a grand jury investigation was threatened and then dropped when Johnson’s committee agreed to alter substantially their emblem and name (from “Presidential” to “Religious” Inaugural Celebration with Love), and to provide their guests with disclaimers edging away from the promise of a presidential appearance. Johnson expected several thousand participants.A donation of 5 each or 0 per couple was indicated on the invitation, but anyone could register to attend both days’ events for . Those paying full price would receive “VIP treatment,” a spokesman said, including two catered dinners and four souvenir books. Coinciding with official inauguration day events, this interfaith celebration was scheduled to include speakers ranging from the mayor of Washington, D.C., to Bill Bright of Campus Crusade, to Paul Yonggi Cho of the world’s largest local church in Seoul, Korea, and such musical entertainers as Dino and Debbie, Danny Gaither, and the Evangel Temple Choir.“What we are trying to establish is a public witness to the world that we who take our faith seriously and who love our country wish to be able to gather together in a spirit of prayer. We are vitally concerned about the health and welfare of our president and other leaders, and we are concerned for the peace of the world. We only want to unite in prayer in behalf of those ends,” Johnson said.Unlike the well-known inaugural balls, which have been part of the inauguration festivities since the days of James Madison, the religious ceremony was nonpartisan. While most of the event’s organizers are Christians, people of other faiths were invited to participate in the common interest of prayer.Science and ReligionNew-Found Allies In The Sociobiology Debate?All is not well on the sociobiology front (see “Sociobiology: Cloned from the Gene Cult,” p. 16). While evangelical scholars are debating how to meet the inroads of this new academic discipline, they may have found allies among some highly regarded anthropologists.According to a report in The Chronicle of Higher Education (Dec. 15, 1980), sociobiology has not “made it” as an organized body of knowledge. At least that’s the view of Jerome Barkow, a Dalhousie University anthropologist. He organized a symposium as part of the annual meeting of the American Anthropological Association to take a look at sociobiology “as the dust settles.”“Dust” in this case refers to the fierce arguments in academia over whether or not sociobiology is indeed a legitimate field of scholarship. Although it had made its way into some introductory textbooks, sociobiology has been criticized as “an attempt to justify genetically the sexist, racist, and elitist status quo in human society.” Those words were put forward at the anthropologists’ 1976 meeting, but they failed to carry in a resolution of condemnation.Since then the debate has simmered. Barkow admits sociobiology has not led to a resurgence of racism, but neither has it solved some of its fundamental theoretical problems. Among them, according to Barkow, are: the relationship between cultural and biological evolution; how to study such concepts as “inclusive fitness”; and the relationship between sociobiology and ecological and biosocial research.Worldwide Church of GodArmstrong Is Unscathed By Legal Attacks, ExposésLegal battles and controversy don’t seem to cramp the style of Herbert W. Armstrong and his Worldwide Church of God (WCG).California Attorney General George Deukmejian in October dropped the state’s two-year-old investigation of the Worldwide Church—initiated after some former members complained that Armstrong and WCG general counsel Stanley Rader siphoned off up to million in church funds for their personal use. Deukmejian complained that the recently adopted “Petris Bill” too severely stripped him of power to prosecute cases involving alleged financial abuses by religious groups. (He dropped investigations of 11 other religious groups as well.)Through it all, the group retained roughly the same membership of about 68,000 worldwide (50,000 in the U.S.). The court battles apparently did not hurt income, which stayed close to the 1979 figure of million. (The WCG has lost 35,000 nonmember contributors since 1976.)Later in the same month Armstrong and Rader flew to Egypt for a meeting with President Anwar Sadat. There, they presented the first 0,000 of million pledged for Sadat’s planned million trifaith worship center at the base of Mount Sinai. Afterward, they flew to Jerusalem to meet with Israeli Prime Minister Menacham Begin.Armstrong’s estranged son, Garner Ted, asserted in a telephone interview that his father’s global tours are represented to WCG members as evangelistic missions. But to foreign officials, Garner Ted charges, Herbert Armstrong is portrayed by advance man Rader as a wealthy philanthropist who is willing to give away large sums of money in exchange for invitations to address distinguished gatherings on such innocuous topics as “The Seven Laws of Success.” A year ago Armstrong got red-carpet treatment in China after donating 0,000 in books to Chinese libraries. (Garner Ted’s own Church of God International, formed after he was expelled from his father’s church in 1978, now claims 70 congregations and about 3,000 members.)Both Garner Ted and his father owe most of their visibility today to the air waves. Herbert Armstrong’s “World Tomorrow” program is now aired on 58 radio and 52 television stations in the U.S. He has a sur-Garner Ted Armstrong prisingly wide electronic media influence in Canada, where his programs air on 53 radio and 81 television stations. Gamer Ted is carried on 50 U.S. radio stations: his fledgling church has experienced defections by several key leaders, who complain he is too autocratic.Herbert Armstrong’s doctrines are rejected by evangelicals: he denies the existence of the Trinity, the soul, hell, and of the Holy Spirit as a person. A distinctive teaching is British Israelism—that Anglo-Saxons are the true Israel, with Britain being the tribe of Ephraim, and the U.S. the tribe Manasseh.More recently, his lifestyle and reputation have been questioned in two controversial books written by former WCG members. WCG officials Sherwin McMichael and Henry Cornwall secured a court order to halt distribution of one of these: David Robinson’s Herbert Armstrong’s Tangled Web (John Hadden Publishers). It contains damaging charges, such as Armstrong’s alleged shocking sexual behavior.Robinson, however, appealed and the ruling was overturned. A million suit against Robinson by the two men was pending, but the recent firing of McMichael from his Washington, D.C., pastorate may have cooled his zeal to pursue the matter further.JOSEPH M. HOPKINSPersonaliaClyde Kilby will retire in July from his job as curator of the Marion Wade Collection at Wheaton College. During his 15 years as curator, Kilby has built up the most comprehensive collections anywhere of C. S. Lewis, Owen Barfield. Dorothy Sayers, and Charles Williams. Other works in the collection include those of G. K. Chesterton, George MacDonald, and J.R.R. Tolkien. All are British authors. Kilby has lectured at more than 50 colleges, edited or authored 10 books, originated Wheaton College’s annual Writers’ Conference 24 years ago, and has been a book reviewer for the (now defunct) New York Herald Tribune.Kenneth L. Barker, professor of semitics and Old Testament at Dallas Theological Seminary, has been named executive secretary of the committee on Bible translations for the New York International Bible Society, as well as its vice-president of Bible translations. Barker will be directing the preparation of a New International Version study Bible. He replaces Edwin Palmer, who died last September.Although federal money may no longer be used to pay for abortions, state money may, and New York is one of the few states still financing abortions—about 50,000 of them a year. Governor Hugh Carey, a Roman Catholic, announced recently that he will reexamine this position. Carey strongly opposes capital punishment, which is illegal in the state.Unitarians and UniversalistsEvangelicals Are Bruised Bucking Maine’S MainlinersSome pastors lose members because of their preaching. Daryl Witmer in tiny Sangerville, Maine, lost his church building, too.Members of the United Church of Sangerville recently vacated the church building where they have met for 30 years, by order of the Northeast District Unitarian Universalist Association, which owns the building. The district office in Portland had notified the church in 1978 that it allegedly violated a trust deed requiring that Unitarian Universalist preaching be maintained there. Pastor Witmer’s self-described “sound Bible preaching ministry” apparently was in violation. As a solution, the church discussed with the district the option of buying the building at a mutually agreed upon price, a course that appeared likely.In the meantime, however, a small group of United Church members became unhappy with Witmer’s conservative theology. They subsequently broke away to form the incorporated First Universalist Church of Sangerville. The Northeast District UUA accepted the Universalist church into full membership last October, and granted the church’s request for the building. The district notified the United Church that it must vacate within 30 days. Since then, the United Church has met in the town hall.The building shuffle caused some hard feelings in this know-everybody town of about 900 (although the United Church chose not to contest the district’s action). Alice Moulton, newly elected president of the Universalist congregation and one who earlier left Witmer’s church, complained that Witmer overemphasized baptism and public profession of faith. (Witmer affirms believer’s baptism, but denies accusations that he ever made rebaptism a prerequisite for membership.) Moulton said she didn’t so much object to Witmer’s “born-again theology,” but that it was preached so narrowly that members not believing exactly like Witmer felt unwelcome.Moulton noted that the new Universalist church has Baptists, Methodists, Universalists (she wasn’t sure if there are any Unitarians), and even some with views similar to Witmer’s. “This small town has only one Protestant church; we believe it’s essential that everyone be able to go to church,” she said. (There is a Roman Catholic church.)Many evangelicals regard New England as a mission field. With that in mind, Witmer sought the Sangerville pastorate six years ago. To him, the recent building hassle showed again that “it’s a rugged thing to move into an area where theological liberalism is entrenched.” While he lacks formal seminary or Bible college training (he left Eastern Mennonite College after two years in favor of study on his own and at Francis Schaeffer’s L’Abri Fellowship), Witmer, 29, established a growing evangelical ministry.Like a circuit rider, Witmer preaches three Sunday services—at Sangerville, and in the nearby communities of Monson (pop. 700) and Abbot (pop. 400). With Sangerville, these form the so-called Sangerville, Abbot, Monson Larger Parish (called “Sam”). Since Witmer’s arrival, all have grown in membership, although they are small by superchurch standards. The Sangerville church has grown from 35 to 100 and the other two churches are up to about 60 members each.Members attribute the growth to an effective small groups and discipleship ministry. A local high school administrator, Charles House, provides leadership in this area, drawing from his experiences at Park Street Church in Boston while a Gordon College student.The churches have a united youth program, and send a newsletter, “Sam-ogram,” to their communities. The Sangerville church has ideas about evangelistic outreach, but local funeral home owner and United Church member Peter Neal said the feeling has been that it is more important in the early going “to build a core group of solid Christians.”Witmer said the recent events have been “a growing experience” for his congregation, which realizes the church is more than a building. However, he admits it’s tough having to leave a building, especially when it is recognized as the church in town.JOHN MAUSTPublishing‘Crying Wind’ Is Back, But Not As A Biography This TimeThe book Crying Wind is back—this time as a “biographical novel.” Harvest House Publishers is distributing the book with the above cover flap description, which is intended to correct discrepancies that caused Moody Press in 1979 to declare the book out of print, along with its sequel. My Searching Heart (CT, Oct. 19, 1979, p. 40).The books describe the Christian conversion and subsequent experiences of a young Indian girl, Crying Wind, which the author, Linda Davison Stafford, ascribed as happening to her. Problems resulted, however, when Moody Press editors learned that Stafford apparently didn’t do all those things. For instance, they were told she did not grow up on a Kickapoo Indian reservation with her grandmother and has little, if any, Indian blood or background.The editors agreed the books carried a strong Christian message, and would have been fine if only they had been presented as fiction. But they weren’t. And the editors felt constrained to remove the books as outside “the editorial standards of Moody Press.” (Later editions had carried a disclaimer that some names, dates, and places had been changed to “protect the privacy of those involved.”)In an interview, Stafford said the problems resulted from “an unfortunate misunderstanding” between herself and Moody Press and from the publisher’s “changes in staff and policies.” Saying she had changed certain names and events to prevent embarrassment to certain family members and friends, she added that Crying Wind “is still based on my life.”Stafford maintained she does have an Indian heritage—that her mother was raised on a Kickapoo reservation, for instance. She remembers dressing U.S.-style during high school, but only as an attempt “to fit in with the crowd.” Married and the mother of four children, Stafford said today she wears Indian garb even at her Divide, Colorado, home. She believes Harvest House’s decision to publish the book is answered prayer, and that it again will be a boost to the cause of Indian missions.Harvest House believes honesty is maintained by calling Crying Wind a biographical novel. Harvest House publisher Bob Hawkins said in a telephone interview, “Because of the moving story, because of what it [Crying Wind] has done for so many people, we felt we should bring it back.”The Irvine, California, publishing company probably had some business motives, too. In a mailing to booksellers, Hawkins wrote, “When Crying Wind was previously published it was a very, very best seller and sold over 80,000 copies [italics his]. Now you can take advantage of the opportunity to help many hundreds, yes thousands, of people across the nation who have been asking for Crying Wind in bookstores.”Moody Press had returned the book copyrights to Stafford, and Harvest House dealt directly with her. Showing her wide-ranging writing interests, she has finished a forthcoming Indian recipe book, Crying Wind’s Kitchen (Intercom), and mentions plans for a romantic novel. She also wants to write a book shedding light on her earlier credibility problems.The PhilippinesAmbitious Growth Goals Pledged By EvangelicalsThe term “historic” in evangelical circles usually describes such major international gatherings as Berlin, Lausanne, or Pattaya. But 488 evangelical leaders representing 81 denominations and parachurch organizations who recently gathered in a two-city “Congress on Discipling a Nation” in the Philippines felt a sense of history in the making that in some respects transcends the significance of those more widely publicized gatherings.These men and women gathered not just to talk about discipling their nation but to commit themselves to “proclaim the evangel of salvation and to persuade men and women so that there will be at least one church in every barangay [ward] or no less than 50,000 congregations in the Philippines by the year 2000 should the Lord tarry.”As the 284 delegates from Cebu City in the Visayan Islands and the 204 from Baguio City in northern Luzon stood to read in unison the “Church-in-Every-Barangay Covenant,” which includes the above quote, they seemed to sense the immensity of the moment. Never before had the body of Christ of one nation committed itself to the systematic planting of a church within easy access of every citizen of the entire country. For the Philippine church, this means adding about 40,000 congregations to their present 10,000 in just 20 years, providing one church for about every 1,500 residents of the island nation.Such a far-reaching commitment by this major slice of the nation’s evangelical leadership follows a decade of solid achievement. Stirrings of this unified assault began with a handful of delegates to Berlin in 1966 and a group of about 60 to the Asia/South Pacific Congress on Evangelism in 1968. These paved the way for the All Philippines Congress on Evangelism in 1970, at which 350 delegates committed themselves to a goal of 10,000 evangelistic Bible study groups throughout the nation. While still rejoicing at having exceeded this goal in March 1973, leaders began praying and talking about a new target. “In order for every citizen in the nation to have a genuine opportunity to make an intelligent decision about Christ,” they reasoned, “we need to have at least one vibrant evangelical congregation in every barrio.”To accomplish such a monumental task would mean growing from about 5,000 congregations to 42,000 just to have a church in every existing barrio. It was assumed that the number of barrios would increase even while they were multiplying their churches.Undaunted, the 60 Filipino delegates to Lausanne in 1974 wrote into their platform for action their commitment to “Establish a local congregation in every barrio in the country.” Another 75 leading pastors, denominational leaders, and missionaries gathered near Manila later that year for an Evangelism/Church Growth Workshop with Vergil Gerber and Donald McGavran. After making faith projections for their denominations and churches, they affirmed the goal of Lausanne, set the actual number at 50,000, and agreed on the year 2000 as the deadline.Could the diverse members of the body of Christ of an entire nation forget their differences and work together toward such an almost unthinkable goal? Researchers Bob Waymire and James Montgomery of O.C. Ministries (OCM, formerly Overseas Crusades) determined to find out early in 1978. Spot checks with 12 denominations revealed an almost six-fold increase in annual rate of church formation in the four years since the workshop. These denominations had planted exactly 1,300 more new churches in that four-year period than they would have had they continued growing at the rate of the previous decade. Furthermore, they had added over 67,000 more converts to their rolls than they would have.Denominations that threw their weight behind specific programs of action seemed to fare best. The “Target 400” program of the Christian and Missionary Alliance (CMA) was ahead of schedule, increasing from 500 churches to 900. Conservative Baptists and Southern Baptists already had growth programs under way before the 1974 workshop; both were experiencing dramatic growth. Nazarenes and Free Methodists were spurting ahead after setting major growth goals at the workshop. New, indigeneous denominations were, if anything, growing fastest of all.Seeing that excellent—sometimes brilliant—progress was being made, Keith Davis, OCM field director for the Philippines, decided it was time to gather the church together again to share victories, plan new strategies, and get an even broader commitment to the task of saturating the nation with evangelical congregations. The two-part Congress on Discipling a Nation during November was the result.Doubling Every Four YearsIt was to be no haphazard event. With the research complete. Montgomery teamed with McGavran to write a 175-page book, The Discipling of a Nation, which all delegates read before the congress. Montgomery and McGavran also spoke at the congress and were joined by such experienced Philippine hands as Leonard Tuggy of the Conservative Baptists, Leslie Hill of the Southern Baptists, and Met Castillo of the CMA. They demonstrated together that discipling an entire nation by planting a congregation in every small community was not only God’s will, but reasonable and possible. That they were convincing was evidenced by some sentiments in the Baguio segment of the congress that perhaps the goal had been set too low!They had a point. The 12 denominations studied (out of more than 75) alone are already growing at a rate that would take them beyond the 50,000 goal by 2000. Furthermore, CMA leaders at the congress set their sights on 40 percent of the goal as they agreed on a “2, 2, 2” program: they want to grow from a current membership of 60,000 in about 900 churches to a membership of 2 million in 20,000 churches by the year 2000. (The program will not become official until all CMA districts in the Philippines agree to it.) The CMA growth is projected, like that of many of the others, on a continuing annual growth of 15 percent. At this rate, membership and churches double every four years. The rate is not difficult to achieve in the very responsive Philippines, but it gets increasingly difficult to maintain as a denomination gets bulkier each succeeding year.Nonetheless, the nearly 500 leaders at the congress seemed incredibly committed to the task. Hardly any grumbled that the goal was unreachable. Furthermore, the unity displayed by participants from an unprecedented 81 different denominations and organizations was something leaders of the previous generation only dreamed about. That three of the four main Filipino speakers were from Pentecostal backgrounds was barely noted, for example.Such unity is possible partly because no group was asked to drop its own program to cooperate in a joint effort. Unity has come by working toward a common goal rather than by linking organizationally.Possibility ThinkingEven if the goal is reached, of course, the whole nation will not have been discipled. Forty thousand new churches would probably add no more than four or five million to the existing one million evangelicals in the Philippines. This would total only 6 to 8 percent of the anticipated population of 80 million by the end of the century.But Philippine leaders argue that with a church in every barrio, the whole nation, with its many different ethnic groups and homogeneous units, could be discipled, for there would be an evangelical congregation for every 1,200 to 1,500 people. A congregation of 100 committed believers could systematically reach out to the remainder of its community, and this would be possible in every community—however the Matthew 28:19 challenge to make disciples “of all nations” might be defined.When Met Castillo of the CMA first read the full text of The Discipling of a Nation, the accuracy of its thesis suddenly burst upon him. “This is it,” he cried out. “All along we have been seeing the task as merely enlarging our borders. Now that we see the end result is discipling the whole nation, we can throw all our denominational energies into it.”Perhaps a whole new way of thinking and doing mission has begun. If so, the church of the Philippines really is making history.NENE RAMIENTOS

After being cleared of mail fraud allegations, organizers of the “Religious Inaugural Celebration …” in Washington, D.C., proceeds on course with plans for this month’s interfaith prayer service that coincides with the change in administration.Charges of misleading the public were directed against James “Johnny” Johnson, who planned the gathering in his capacity as an independent, evangelical lay minister. (He serves as vice-president of the Full Gospel Business Men’s Fellowship, and was assistant secretary of the navy under Richard Nixon. Johnson also has close ties with the President-elect, who appointed him director of veteran’s affairs in California in 1967. He was the first black ever named to a state cabinet post.)In October, Johnson’s independent inaugural committee issued more than 40,000 formal invitations, which bore a gold, embossed eagle emblem. The official-looking invitations requested attendance at a “nonsectarian, nonpartisan, nonpolitical” prayer meeting on January 19 and 20 at Washington’s Starplex Armory. After the election, Ronald Reagan’s official inaugural committee complained that the invitations would confuse and mislead recipients by suggesting that purchasers of the tickets would be treated to an appearance by either Reagan or Vice-president-elect George Bush. In fact, neither one had agreed to attend the festivities, though both were invited.As a result, a grand jury investigation was threatened and then dropped when Johnson’s committee agreed to alter substantially their emblem and name (from “Presidential” to “Religious” Inaugural Celebration with Love), and to provide their guests with disclaimers edging away from the promise of a presidential appearance. Johnson expected several thousand participants.A donation of 5 each or 0 per couple was indicated on the invitation, but anyone could register to attend both days’ events for . Those paying full price would receive “VIP treatment,” a spokesman said, including two catered dinners and four souvenir books. Coinciding with official inauguration day events, this interfaith celebration was scheduled to include speakers ranging from the mayor of Washington, D.C., to Bill Bright of Campus Crusade, to Paul Yonggi Cho of the world’s largest local church in Seoul, Korea, and such musical entertainers as Dino and Debbie, Danny Gaither, and the Evangel Temple Choir.“What we are trying to establish is a public witness to the world that we who take our faith seriously and who love our country wish to be able to gather together in a spirit of prayer. We are vitally concerned about the health and welfare of our president and other leaders, and we are concerned for the peace of the world. We only want to unite in prayer in behalf of those ends,” Johnson said.Unlike the well-known inaugural balls, which have been part of the inauguration festivities since the days of James Madison, the religious ceremony was nonpartisan. While most of the event’s organizers are Christians, people of other faiths were invited to participate in the common interest of prayer.Science and ReligionNew-Found Allies In The Sociobiology Debate?All is not well on the sociobiology front (see “Sociobiology: Cloned from the Gene Cult,” p. 16). While evangelical scholars are debating how to meet the inroads of this new academic discipline, they may have found allies among some highly regarded anthropologists.According to a report in The Chronicle of Higher Education (Dec. 15, 1980), sociobiology has not “made it” as an organized body of knowledge. At least that’s the view of Jerome Barkow, a Dalhousie University anthropologist. He organized a symposium as part of the annual meeting of the American Anthropological Association to take a look at sociobiology “as the dust settles.”“Dust” in this case refers to the fierce arguments in academia over whether or not sociobiology is indeed a legitimate field of scholarship. Although it had made its way into some introductory textbooks, sociobiology has been criticized as “an attempt to justify genetically the sexist, racist, and elitist status quo in human society.” Those words were put forward at the anthropologists’ 1976 meeting, but they failed to carry in a resolution of condemnation.Since then the debate has simmered. Barkow admits sociobiology has not led to a resurgence of racism, but neither has it solved some of its fundamental theoretical problems. Among them, according to Barkow, are: the relationship between cultural and biological evolution; how to study such concepts as “inclusive fitness”; and the relationship between sociobiology and ecological and biosocial research.Worldwide Church of GodArmstrong Is Unscathed By Legal Attacks, ExposésLegal battles and controversy don’t seem to cramp the style of Herbert W. Armstrong and his Worldwide Church of God (WCG).California Attorney General George Deukmejian in October dropped the state’s two-year-old investigation of the Worldwide Church—initiated after some former members complained that Armstrong and WCG general counsel Stanley Rader siphoned off up to million in church funds for their personal use. Deukmejian complained that the recently adopted “Petris Bill” too severely stripped him of power to prosecute cases involving alleged financial abuses by religious groups. (He dropped investigations of 11 other religious groups as well.)Through it all, the group retained roughly the same membership of about 68,000 worldwide (50,000 in the U.S.). The court battles apparently did not hurt income, which stayed close to the 1979 figure of million. (The WCG has lost 35,000 nonmember contributors since 1976.)Later in the same month Armstrong and Rader flew to Egypt for a meeting with President Anwar Sadat. There, they presented the first 0,000 of million pledged for Sadat’s planned million trifaith worship center at the base of Mount Sinai. Afterward, they flew to Jerusalem to meet with Israeli Prime Minister Menacham Begin.Armstrong’s estranged son, Garner Ted, asserted in a telephone interview that his father’s global tours are represented to WCG members as evangelistic missions. But to foreign officials, Garner Ted charges, Herbert Armstrong is portrayed by advance man Rader as a wealthy philanthropist who is willing to give away large sums of money in exchange for invitations to address distinguished gatherings on such innocuous topics as “The Seven Laws of Success.” A year ago Armstrong got red-carpet treatment in China after donating 0,000 in books to Chinese libraries. (Garner Ted’s own Church of God International, formed after he was expelled from his father’s church in 1978, now claims 70 congregations and about 3,000 members.)Both Garner Ted and his father owe most of their visibility today to the air waves. Herbert Armstrong’s “World Tomorrow” program is now aired on 58 radio and 52 television stations in the U.S. He has a sur-Garner Ted Armstrong prisingly wide electronic media influence in Canada, where his programs air on 53 radio and 81 television stations. Gamer Ted is carried on 50 U.S. radio stations: his fledgling church has experienced defections by several key leaders, who complain he is too autocratic.Herbert Armstrong’s doctrines are rejected by evangelicals: he denies the existence of the Trinity, the soul, hell, and of the Holy Spirit as a person. A distinctive teaching is British Israelism—that Anglo-Saxons are the true Israel, with Britain being the tribe of Ephraim, and the U.S. the tribe Manasseh.More recently, his lifestyle and reputation have been questioned in two controversial books written by former WCG members. WCG officials Sherwin McMichael and Henry Cornwall secured a court order to halt distribution of one of these: David Robinson’s Herbert Armstrong’s Tangled Web (John Hadden Publishers). It contains damaging charges, such as Armstrong’s alleged shocking sexual behavior.Robinson, however, appealed and the ruling was overturned. A million suit against Robinson by the two men was pending, but the recent firing of McMichael from his Washington, D.C., pastorate may have cooled his zeal to pursue the matter further.JOSEPH M. HOPKINSPersonaliaClyde Kilby will retire in July from his job as curator of the Marion Wade Collection at Wheaton College. During his 15 years as curator, Kilby has built up the most comprehensive collections anywhere of C. S. Lewis, Owen Barfield. Dorothy Sayers, and Charles Williams. Other works in the collection include those of G. K. Chesterton, George MacDonald, and J.R.R. Tolkien. All are British authors. Kilby has lectured at more than 50 colleges, edited or authored 10 books, originated Wheaton College’s annual Writers’ Conference 24 years ago, and has been a book reviewer for the (now defunct) New York Herald Tribune.Kenneth L. Barker, professor of semitics and Old Testament at Dallas Theological Seminary, has been named executive secretary of the committee on Bible translations for the New York International Bible Society, as well as its vice-president of Bible translations. Barker will be directing the preparation of a New International Version study Bible. He replaces Edwin Palmer, who died last September.Although federal money may no longer be used to pay for abortions, state money may, and New York is one of the few states still financing abortions—about 50,000 of them a year. Governor Hugh Carey, a Roman Catholic, announced recently that he will reexamine this position. Carey strongly opposes capital punishment, which is illegal in the state.Unitarians and UniversalistsEvangelicals Are Bruised Bucking Maine’S MainlinersSome pastors lose members because of their preaching. Daryl Witmer in tiny Sangerville, Maine, lost his church building, too.Members of the United Church of Sangerville recently vacated the church building where they have met for 30 years, by order of the Northeast District Unitarian Universalist Association, which owns the building. The district office in Portland had notified the church in 1978 that it allegedly violated a trust deed requiring that Unitarian Universalist preaching be maintained there. Pastor Witmer’s self-described “sound Bible preaching ministry” apparently was in violation. As a solution, the church discussed with the district the option of buying the building at a mutually agreed upon price, a course that appeared likely.In the meantime, however, a small group of United Church members became unhappy with Witmer’s conservative theology. They subsequently broke away to form the incorporated First Universalist Church of Sangerville. The Northeast District UUA accepted the Universalist church into full membership last October, and granted the church’s request for the building. The district notified the United Church that it must vacate within 30 days. Since then, the United Church has met in the town hall.The building shuffle caused some hard feelings in this know-everybody town of about 900 (although the United Church chose not to contest the district’s action). Alice Moulton, newly elected president of the Universalist congregation and one who earlier left Witmer’s church, complained that Witmer overemphasized baptism and public profession of faith. (Witmer affirms believer’s baptism, but denies accusations that he ever made rebaptism a prerequisite for membership.) Moulton said she didn’t so much object to Witmer’s “born-again theology,” but that it was preached so narrowly that members not believing exactly like Witmer felt unwelcome.Moulton noted that the new Universalist church has Baptists, Methodists, Universalists (she wasn’t sure if there are any Unitarians), and even some with views similar to Witmer’s. “This small town has only one Protestant church; we believe it’s essential that everyone be able to go to church,” she said. (There is a Roman Catholic church.)Many evangelicals regard New England as a mission field. With that in mind, Witmer sought the Sangerville pastorate six years ago. To him, the recent building hassle showed again that “it’s a rugged thing to move into an area where theological liberalism is entrenched.” While he lacks formal seminary or Bible college training (he left Eastern Mennonite College after two years in favor of study on his own and at Francis Schaeffer’s L’Abri Fellowship), Witmer, 29, established a growing evangelical ministry.Like a circuit rider, Witmer preaches three Sunday services—at Sangerville, and in the nearby communities of Monson (pop. 700) and Abbot (pop. 400). With Sangerville, these form the so-called Sangerville, Abbot, Monson Larger Parish (called “Sam”). Since Witmer’s arrival, all have grown in membership, although they are small by superchurch standards. The Sangerville church has grown from 35 to 100 and the other two churches are up to about 60 members each.Members attribute the growth to an effective small groups and discipleship ministry. A local high school administrator, Charles House, provides leadership in this area, drawing from his experiences at Park Street Church in Boston while a Gordon College student.The churches have a united youth program, and send a newsletter, “Sam-ogram,” to their communities. The Sangerville church has ideas about evangelistic outreach, but local funeral home owner and United Church member Peter Neal said the feeling has been that it is more important in the early going “to build a core group of solid Christians.”Witmer said the recent events have been “a growing experience” for his congregation, which realizes the church is more than a building. However, he admits it’s tough having to leave a building, especially when it is recognized as the church in town.JOHN MAUSTPublishing‘Crying Wind’ Is Back, But Not As A Biography This TimeThe book Crying Wind is back—this time as a “biographical novel.” Harvest House Publishers is distributing the book with the above cover flap description, which is intended to correct discrepancies that caused Moody Press in 1979 to declare the book out of print, along with its sequel. My Searching Heart (CT, Oct. 19, 1979, p. 40).The books describe the Christian conversion and subsequent experiences of a young Indian girl, Crying Wind, which the author, Linda Davison Stafford, ascribed as happening to her. Problems resulted, however, when Moody Press editors learned that Stafford apparently didn’t do all those things. For instance, they were told she did not grow up on a Kickapoo Indian reservation with her grandmother and has little, if any, Indian blood or background.The editors agreed the books carried a strong Christian message, and would have been fine if only they had been presented as fiction. But they weren’t. And the editors felt constrained to remove the books as outside “the editorial standards of Moody Press.” (Later editions had carried a disclaimer that some names, dates, and places had been changed to “protect the privacy of those involved.”)In an interview, Stafford said the problems resulted from “an unfortunate misunderstanding” between herself and Moody Press and from the publisher’s “changes in staff and policies.” Saying she had changed certain names and events to prevent embarrassment to certain family members and friends, she added that Crying Wind “is still based on my life.”Stafford maintained she does have an Indian heritage—that her mother was raised on a Kickapoo reservation, for instance. She remembers dressing U.S.-style during high school, but only as an attempt “to fit in with the crowd.” Married and the mother of four children, Stafford said today she wears Indian garb even at her Divide, Colorado, home. She believes Harvest House’s decision to publish the book is answered prayer, and that it again will be a boost to the cause of Indian missions.Harvest House believes honesty is maintained by calling Crying Wind a biographical novel. Harvest House publisher Bob Hawkins said in a telephone interview, “Because of the moving story, because of what it [Crying Wind] has done for so many people, we felt we should bring it back.”The Irvine, California, publishing company probably had some business motives, too. In a mailing to booksellers, Hawkins wrote, “When Crying Wind was previously published it was a very, very best seller and sold over 80,000 copies [italics his]. Now you can take advantage of the opportunity to help many hundreds, yes thousands, of people across the nation who have been asking for Crying Wind in bookstores.”Moody Press had returned the book copyrights to Stafford, and Harvest House dealt directly with her. Showing her wide-ranging writing interests, she has finished a forthcoming Indian recipe book, Crying Wind’s Kitchen (Intercom), and mentions plans for a romantic novel. She also wants to write a book shedding light on her earlier credibility problems.The PhilippinesAmbitious Growth Goals Pledged By EvangelicalsThe term “historic” in evangelical circles usually describes such major international gatherings as Berlin, Lausanne, or Pattaya. But 488 evangelical leaders representing 81 denominations and parachurch organizations who recently gathered in a two-city “Congress on Discipling a Nation” in the Philippines felt a sense of history in the making that in some respects transcends the significance of those more widely publicized gatherings.These men and women gathered not just to talk about discipling their nation but to commit themselves to “proclaim the evangel of salvation and to persuade men and women so that there will be at least one church in every barangay [ward] or no less than 50,000 congregations in the Philippines by the year 2000 should the Lord tarry.”As the 284 delegates from Cebu City in the Visayan Islands and the 204 from Baguio City in northern Luzon stood to read in unison the “Church-in-Every-Barangay Covenant,” which includes the above quote, they seemed to sense the immensity of the moment. Never before had the body of Christ of one nation committed itself to the systematic planting of a church within easy access of every citizen of the entire country. For the Philippine church, this means adding about 40,000 congregations to their present 10,000 in just 20 years, providing one church for about every 1,500 residents of the island nation.Such a far-reaching commitment by this major slice of the nation’s evangelical leadership follows a decade of solid achievement. Stirrings of this unified assault began with a handful of delegates to Berlin in 1966 and a group of about 60 to the Asia/South Pacific Congress on Evangelism in 1968. These paved the way for the All Philippines Congress on Evangelism in 1970, at which 350 delegates committed themselves to a goal of 10,000 evangelistic Bible study groups throughout the nation. While still rejoicing at having exceeded this goal in March 1973, leaders began praying and talking about a new target. “In order for every citizen in the nation to have a genuine opportunity to make an intelligent decision about Christ,” they reasoned, “we need to have at least one vibrant evangelical congregation in every barrio.”To accomplish such a monumental task would mean growing from about 5,000 congregations to 42,000 just to have a church in every existing barrio. It was assumed that the number of barrios would increase even while they were multiplying their churches.Undaunted, the 60 Filipino delegates to Lausanne in 1974 wrote into their platform for action their commitment to “Establish a local congregation in every barrio in the country.” Another 75 leading pastors, denominational leaders, and missionaries gathered near Manila later that year for an Evangelism/Church Growth Workshop with Vergil Gerber and Donald McGavran. After making faith projections for their denominations and churches, they affirmed the goal of Lausanne, set the actual number at 50,000, and agreed on the year 2000 as the deadline.Could the diverse members of the body of Christ of an entire nation forget their differences and work together toward such an almost unthinkable goal? Researchers Bob Waymire and James Montgomery of O.C. Ministries (OCM, formerly Overseas Crusades) determined to find out early in 1978. Spot checks with 12 denominations revealed an almost six-fold increase in annual rate of church formation in the four years since the workshop. These denominations had planted exactly 1,300 more new churches in that four-year period than they would have had they continued growing at the rate of the previous decade. Furthermore, they had added over 67,000 more converts to their rolls than they would have.Denominations that threw their weight behind specific programs of action seemed to fare best. The “Target 400” program of the Christian and Missionary Alliance (CMA) was ahead of schedule, increasing from 500 churches to 900. Conservative Baptists and Southern Baptists already had growth programs under way before the 1974 workshop; both were experiencing dramatic growth. Nazarenes and Free Methodists were spurting ahead after setting major growth goals at the workshop. New, indigeneous denominations were, if anything, growing fastest of all.Seeing that excellent—sometimes brilliant—progress was being made, Keith Davis, OCM field director for the Philippines, decided it was time to gather the church together again to share victories, plan new strategies, and get an even broader commitment to the task of saturating the nation with evangelical congregations. The two-part Congress on Discipling a Nation during November was the result.Doubling Every Four YearsIt was to be no haphazard event. With the research complete. Montgomery teamed with McGavran to write a 175-page book, The Discipling of a Nation, which all delegates read before the congress. Montgomery and McGavran also spoke at the congress and were joined by such experienced Philippine hands as Leonard Tuggy of the Conservative Baptists, Leslie Hill of the Southern Baptists, and Met Castillo of the CMA. They demonstrated together that discipling an entire nation by planting a congregation in every small community was not only God’s will, but reasonable and possible. That they were convincing was evidenced by some sentiments in the Baguio segment of the congress that perhaps the goal had been set too low!They had a point. The 12 denominations studied (out of more than 75) alone are already growing at a rate that would take them beyond the 50,000 goal by 2000. Furthermore, CMA leaders at the congress set their sights on 40 percent of the goal as they agreed on a “2, 2, 2” program: they want to grow from a current membership of 60,000 in about 900 churches to a membership of 2 million in 20,000 churches by the year 2000. (The program will not become official until all CMA districts in the Philippines agree to it.) The CMA growth is projected, like that of many of the others, on a continuing annual growth of 15 percent. At this rate, membership and churches double every four years. The rate is not difficult to achieve in the very responsive Philippines, but it gets increasingly difficult to maintain as a denomination gets bulkier each succeeding year.Nonetheless, the nearly 500 leaders at the congress seemed incredibly committed to the task. Hardly any grumbled that the goal was unreachable. Furthermore, the unity displayed by participants from an unprecedented 81 different denominations and organizations was something leaders of the previous generation only dreamed about. That three of the four main Filipino speakers were from Pentecostal backgrounds was barely noted, for example.Such unity is possible partly because no group was asked to drop its own program to cooperate in a joint effort. Unity has come by working toward a common goal rather than by linking organizationally.Possibility ThinkingEven if the goal is reached, of course, the whole nation will not have been discipled. Forty thousand new churches would probably add no more than four or five million to the existing one million evangelicals in the Philippines. This would total only 6 to 8 percent of the anticipated population of 80 million by the end of the century.But Philippine leaders argue that with a church in every barrio, the whole nation, with its many different ethnic groups and homogeneous units, could be discipled, for there would be an evangelical congregation for every 1,200 to 1,500 people. A congregation of 100 committed believers could systematically reach out to the remainder of its community, and this would be possible in every community—however the Matthew 28:19 challenge to make disciples “of all nations” might be defined.When Met Castillo of the CMA first read the full text of The Discipling of a Nation, the accuracy of its thesis suddenly burst upon him. “This is it,” he cried out. “All along we have been seeing the task as merely enlarging our borders. Now that we see the end result is discipling the whole nation, we can throw all our denominational energies into it.”Perhaps a whole new way of thinking and doing mission has begun. If so, the church of the Philippines really is making history.NENE RAMIENTOSAmong all Americans, 24 percent said their faith had been strengthened in April, compared to the 28 percent in the summer.

About a third of Americans believe the pandemic offers a lesson for humanity sent by God (35%), according to a prior Pew survey. A similar share (37%) believe there is a lesson to learn but it was not sent by God.

Pew surveyed 14,276 adults by telephone from June 10 to August 3 in the 14 countries, selected for being advanced economies.

Pew noted that “all of the countries surveyed were under social distancing and/or national lockdown orders due to COVID-19,” however “not all countries have experienced the disease in the same way” and the pandemic “situation has changed substantially since the survey was conducted.”

During the fielding period, Australia, Japan, and the United States had rising numbers of infections, while Italy and some other European countries had started to recover from the large number of cases reported in April and May. Nearly all countries surveyed experienced significant spikes in infections and deaths in the fall and winter.

Pew also found a third of respondents said their family’s relationship had strengthened as a result of the pandemic (global median: 32%). About 4 in 10 Spaniards, Italians, Americans, Brits, and Canadians reported this, as did 3 in 10 Belgians, French, Australians, and Swedes.

Germans led the way among those who said family relationships had weakened (13%), followed by Belgians (11%) and Koreans (10%).

Yong J. Cho, outgoing general secretary of the Korea World Missions Association, told CT he saw “two interpretations” of Pew’s findings among Koreans.

First, it reflects that South Korea is a “strong group-oriented society.” “The whole country has been affected as a group. General media were very critical of the Christian church and her responses to the pandemic,” Cho, a pastor and PhD who this week became the new president of Global Hope, told CT. “During the survey period, there was very strong anti-government demonstrations among the conservative churches. The current government is generally against evangelical or conservative Christianity in Korea. That is one reason why people think that religious faith in Korea has weakened.”

Second, Korean churches place a high value on in-person communal worship. “Christianity and other religions in Korea have emphasized the physical presence as an essential element of worship,” he said. “Because of COVID-19, the very restricted physical gathering of the churches has weakened the passion of faith.”

The findings in Italy were not surprising, said Leonardo de Chirico, vice chairman of the Italian Evangelical Alliance. Though churches were closed for about three months, the majority Roman Catholic Church encouraged both positive thinking and traditional practices such as indulgences and Marian rosaries, including one led by Pope Francis himself on national TV.

“What kind of faith is it? Is it wishful thinking? Is it a self-empowerment mantra? Is it a hope that all will go well and that we will soon go back to normal?” the pastor of Rome’s Breccia di Roma church told CT. “But where is God, where is the gospel?”

Chirico said evangelical churches in Italy also faced the “unprecedented challenge” of living in community, evangelizing, and caring for the elderly and the vulnerable—all at a public health-mandated distance.

“The presence [of churches] on the internet has exploded quantitatively, but it does not mean that we have succeeded to manage it well,” he said. “The long-term consequences are still to be envisaged, let alone tackled. Will real community relationships resume? Will participation and involvement be a feature of future church life? … We walk step by step, but it’s not clear where we are going in terms of the overall gospel dynamic. It is sobering, and it should lead us on our knees to pray.”

This post will be updated.