Christians around the globe share concerns about the application of fast-advancing gene-editing technology, making them more cautious about the research and its potential application to alter a baby’s genetic makeup, according to a new survey.

Trevor Stammers, bioethicist and former chair of the UK-based Christian Medical Fellowship, called gene editing “arguably the most significant medical advance of the millennium to date” and said, “it is certainly here to stay.”

As the gene editing has moved from possibility to reality, this year the Pew Research Center found that across 20 countries, most people are open to using the technology to treat disease in babies.

The team of researchers that developed CRISPR “scissors”—a tool to insert, replace, and remove particular segments of cell DNA—won the 2020 Nobel Prize in chemistry, and scientists are already discussing possible uses of gene editing in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The bioethical concerns around editing human DNA aren’t as familiar to everyday Christians as abortion and assisted suicide, medical ethicist Daniel J. Hurst told CT, but they are growing more urgent.

In 2018, a Chinese scientist performed experimental gene editing on a set of twins, altering their DNA to increase their resistance to HIV. Members of the scientific community condemned his methodology and urged researchers not to put “the technical cart before the ethical horse,” recounted Hurst, a Christian and the director of medical professionalism, ethics, and humanities at Rowan University.

Those with a special concern for upholding life and honoring God’s creation tend to approach this field of research with additional unease.

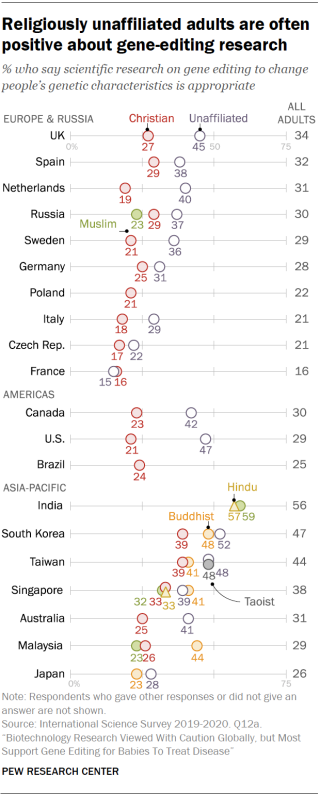

Christians in the US are half as likely as the religiously unaffiliated to believe scientific research on gene editing is an appropriate use of technology (21% vs. 47%), the widest gap among the countries surveyed.

Believers in Canada, the UK, the Netherlands, Sweden, Italy, and Spain also lagged behind the unaffiliated, though both demographics disapproved of gene-editing research.

In France, where approval levels were lowest, Christians and the unaffiliated felt about the same (16% vs. 15% said it was appropriate).

Few people, regardless of faith, considered it appropriate to alter genetic makeup to make a baby more intelligent; overall, 82 percent disapproved.

But many believe scientists should work on gene editing to prevent or cure diseases, even if that means using “germline editing” techniques that alter the DNA in a human germ cell (an egg or sperm) or an embryo.

“Most gene editing researchers see the creation and destruction of embryos as an intrinsic necessity … and many Christians will find this unethical—the end point here being neither healing nor enhancement of the embryo involved,” wrote Stammers.

In the UK, the Christian Medical Fellowship spoke out against a decision by the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority decision to allow genome modification of human embryos fertilized through in vitro fertilization.

But some Christians also see a case for CRISPR technology as a tool for healing.

In a US survey CT covered in 2018, Pew found that 61 percent of both white evangelicals and black Protestants said gene editing to help cure a disease at birth was an appropriate use of medical technology, while fewer were comfortable with the idea of using gene editing to reduce disease over a lifetime. Around half of black Protestants and 45 percent of white evangelicals approved of using it for future conditions.

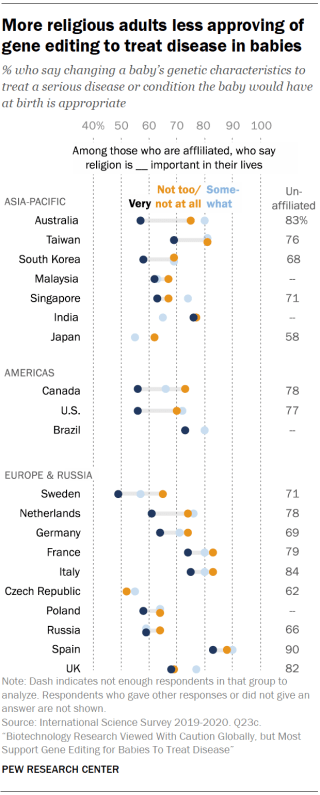

In the 2020 report, a median of 70 percent of people across the 20 countries said they approved of gene editing to treat congenital conditions that babies would be born with, and 60 percent approved of using it to reduce the risk of a disease that could develop later.

Majorities of believers who considered religion very important to them approved of gene editing to treat disease at birth, though people who said religion was less important were even more in favor of the treatments.

“What I think is still missing is solid theological reasoning, within the Christian community, about CRISPR. Why exactly does the doctrine of the imago Dei mean that we should be wary about germline editing?” said Nathan Barczi, executive director of The Octect Collaborative and associate pastor of Christ the King Church in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

“If CRISPR could be practiced and developed without the destruction of human embryos, would that make it okay? Does our concern for the sanctity of human life apply to the unborn (as it should!) only, or does it extend more broadly to that, to how we think about what it means for ourselves and our fellow humans—with all of our limitations, constraints, and differences—to be fully human, bearing God’s image?” said Barczi, who previously wrote about gene editing for CT. “I think there’s lots of work left to be done there.”

Jason Thacker, chair of research in technology ethics at the Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention, agrees. He sees Christian formation around the sanctity of life and the call to love God and neighbor as the basis of the church’s response to potential issues in biotechnology.

“The church needs more people steeped in these truths and speaking clearly to the pressing ethical issues surrounding all forms of technology,” he said. “It will take a concerted effort from all of us to raise awareness about the life-altering issues at stake in these debates.”

Age is consistently a factor in how people approach gene editing. Younger people across the countries surveyed were more open to the technology than older populations.

Pew also found that, in most countries, between a third and half of Christians say their religious beliefs conflict with science.

The perceived disparity between faith and science was highest in parts of Asia, with 64 percent of Christians in South Korea and 58 percent of Christians in Singapore reporting some conflict. It was lowest in Sweden, where just 15 percent of Christians saw conflict.