Two North Korean families prayed silently on the prison floor—making certain to keep their eyes open. Another detainee, a veteran of Kim Jong-il’s gulag system, asked them if they were afraid.

“No,” one of the mothers replied. “Jesus looks over us.”

The detainee began to cry, knowing the fate that awaited them. The next day, they were sent to Chongjin Susong political prison camp, and have not been heard from since.

But elsewhere in Onsong County’s pre-trial detention center, however, a different Christian prisoner closed his eyes. After confessing he was at prayer, his fellow detainees collectively assaulted him—afraid he would bring trouble on them all.

These are just some of the harrowing stories told in a 2020 report on religious persecution in North Korea. Groundbreaking in its scope, it is drawn from the testimony of 117 defectors, cross-referenced with known data.

Produced by the Korea Future Initiative (KFI), Persecuting Faith reveals 273 documented victims—76 of whom are still in the North Korean penal system. It names 54 individual perpetrators, including 34 with identifying information.

KFI hopes the information will inform future Global Magnitsky sanctions, applied against individual human rights violators by the United States and other Western nations.

Drawn from experiences stretching from 1990 to 2019, KFI’s report lists scores of violations. These include 36 instances of punishment meted out to family members, 36 instances of torture, and 20 executions. Women and girls represent 60 percent of the victims.

And Christians are disproportionately imprisoned—by far.

Open Doors, which has ranked North Korea No. 1 in its World Watch List for 19 straight years, estimates there are 300,000 Christians in the population of 25 million. Tens of thousands of these occupy the gulag.

Of KFI’s 273 victims, Christians total nearly 80 percent: 215 cases.

Shamanism, the folk religion of North Korea that is also persecuted by the regime, represents all but two of the rest.

KFI identifies itself as “non-religious, but not secular.”

“The report confirms what Christians already thought about persecution in North Korea,” said James Burt, KFI chief strategy officer and a co-author of the report.

“But it also breaks it down further, to give a granular understanding of how the government deals with religion.”

In the past, some victim testimony has proven false or embellished. Given the lack of access, much is difficult to verify. But often, similar stories are heard over and over again.

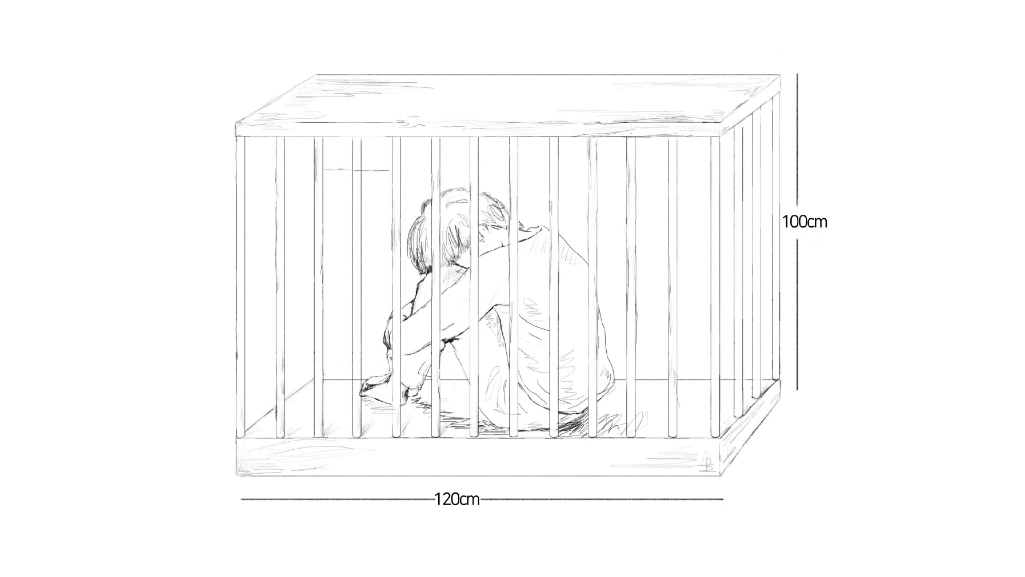

The majority of violations are arbitrary arrest, detention, imprisonment, and interrogation—with several suffered by the same individuals. These are linked to 85 physical locations—10 of which are penal facilities within China—mapping the geography of a country to which few are permitted access. And the report details the North Korean government bodies that oversee its network of secret police and citizen informant programs.

KFI has also obtained access to internal documents that provide the philosophy behind the repression.

“The American imperialists have used religion as a tool to invade our country in the past,” states the Korean Workers’ Party Transcendental Guidance System. “And today, they are viciously plotting to spread religion to … crush our republic.”

Jan Vermeer, the pseudonym used by the communications director for Open Doors Asia, appreciated the documentation work of KFI.

But he wished to take the “why” of persecution a step further.

North Korea officially traces its clash with Christianity to 1866, when it beheaded a missionary who arrived with an American naval vessel seeking to open trade relations.

But by 1907, there was a Christian revival in the now-capital of Pyongyang. And Christians became very popular for their resistance to Japanese occupation, refusing to worship the emperor. By 1945, when the Korean peninsula was divided by Soviet and American occupation, there were 500,000 Christians in North Korea—including both parents of Kim Il-sung, the communist founder.

Born in 1912, Kim would go on to mark his birth as the dividing point of history, imitating Jesus’ role in the Western calendar. Engaging in near-deification, his word became law.

The cult of personality continued with his son, Kim Jong-il, and grandson, current leader Kim Jong-un—instilled at the earliest levels of education.

KFI’s foreword is written by Ju Il-lyong, an exiled human rights activist who testified before President Donald Trump at the 2019 Ministerial to Advance Religious Freedom. In the report, he described two stories learned while growing up in North Korea.

In one, an American missionary etched with acid the word “thief” into the forehead of a child who picked an apple from his orchard. In the other, a father was honored for running into his burning home to rescue the portraits of Kim Il-sung and son, sacrificing his daughter for the sake of the Supreme Leaders.

“Often we think of North Korea as a weird country ruled by a line of nutty dictators,” said Vermeer. “But these are very smart people who have left no room for any type of religion, because that would set the people free in their mind.”

Some are trying.

One example (not provided by Vermeer) involves a former North Korean agricultural researcher who fell afoul of the government when he advocated for private ownership of land. After relocating to South Korea, he became a Christian, and now engineers balloons to cross the border and release their content at just the right location and altitude.

“It was the Christian missionaries who extended helping hands to me when I was in crisis and had serious problems,” reads his pamphlet. “Through them, I found out that their belief is totally contrary to what I was told in North Korea.

“They preach ‘love,’ and tell us to love each other to the extent of loving your enemy … We must love each other, North and South Korea.”

But across the border, possession of such materials in the north can be damning. Many anecdotes in the KFI report describe the Bible or Christian literature as the evidence that led to imprisonment. One North Korean was tied to a stake and executed in front of 1,000 people at an outdoor market.

Some Christians have fled in search of religious freedom, Burt said. But it is far from the only cause. Poverty, starvation, and a culture of misogyny and sexual harassment have led thousands of North Koreans to sneak or bribe their way through border patrols into China.

And once they have crossed the border—seeking a circuitous route to South Korea, many end up as sex slaves to poor farmers in an illegal underworld that generates $105 million per year.

“There are two types of people who pick them up,” said Ed Brown, the American general secretary for Stefanus, a Norwegian Christian organization advocating for freedom of religion or belief.

“Abusive human traffickers, and Christians—who risk their lives to move them from safe house to safe house, and then out of China.”

Stefanus produced Saved: Escape from Kim’s Regime, to tell their story. An official selection of the 2019 International Christian Film and Music Festival, it features the work of Helping Hands Korea (HHK), which has assisted vulnerable North Koreans since 1996.

Beside participating in the modern-day underground railroad, HHK also send seeds into North Korea, so that people in the lowest class of the songbun social class system—labeled “hostile” by the regime and denied access to centralized goods—can grow their own crops.

Stefanus supports such work—and other programs that cannot be named—to build a fledgling civil society in North Korea.

They want the nation to be ready, when freedom comes.

A different approach is taken by Reah International, which seeks to connect Christians with opportunities to serve the people of North Korea. Its method of engagement facilitates humanitarian aid, education, and economic development—working in cooperation with the government.

“Those who can bring lasting change to North Korea are North Koreans,” said Janice Yoon, Reah’s communication coordinator.

“Our approach allows us to alleviate suffering, decrease their isolation, and provide different narratives to their prejudices—as we build relationships over time.”

There can be a tension between the justice work of human rights advocacy, Yoon said, and mercy-oriented humanitarian and spiritual ministry. But it need not be so. Even if there is passionate disagreement over the best approaches, each can be an arm of the body of Christ.

The “not secular” KFI agrees.

“Human rights is not only about investigation and documentation, it is social integration and support,” said Burt. “Groups that help these victims are incredibly important, and an essential part of the work.”

But per KFI’s report, documentation is essential.

“We have not just documented the violations, but also the perpetrators,” he said. “We collect data and constantly update it, so that no one can claim they didn’t know what was happening.”

The anecdotes in the report—only Volume 1, according to KFI—speak volumes.

In 2018, a 38-year-old male was detained in North Pyongan Provincial Ministry of State Security holding center. Peering into the prisoner’s cell, a correctional officer asked, “Why did you do what the state forbids?”

The prisoner, whose crime was to possess a Bible, responded, “I just wanted to know for myself.”