While white evangelicals remain a core voting bloc for President Donald Trump, in the 2020 race against Joe Biden white Catholics are expected to be a crucial demographic.

Data indicates that Biden—a lifelong member of the Catholic church—may shift the white Catholic vote away from the Republican leanings it held for the past four presidential elections and make it a true swing vote going forward.

Even small changes among Catholics could affect the electoral outcome, particularly in swing states. In 2016, Donald Trump won Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Florida by narrow margins of 1 percent to 1.2 percent of the votes cast.

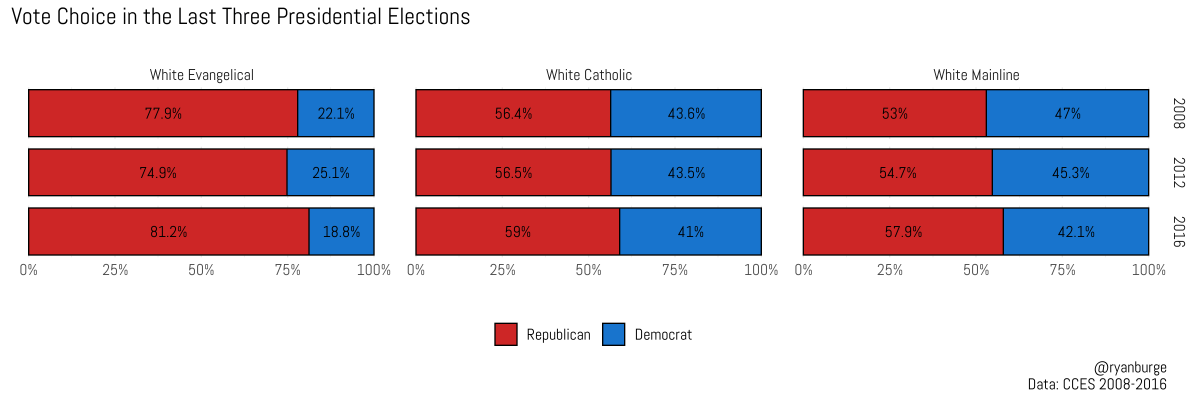

Despite all the chatter around the strong support that Trump received from white Christians and white evangelicals last election, their voting patterns in 2016 were relatively consistent with elections going back to 2008.

Across Christian traditions, white voters have been relatively stable but have slowly drifted toward the Republican Party by 3–4 percentage points in eight years. (Nonwhite Christians, particularly black Protestants, have historically favored the Democratic Party by strong margins and are expected to continue to do so this year.)

For instance, in the 2008 presidential matchup, 78 percent of white evangelicals cast their ballots for Barack Obama’s Republican challenger, John McCain. Trump did just a few points better in 2016, with 81 percent.

The partisan split among white Catholics and white mainline Protestants mostly held steady as well. In both 2008 and 2012, 56 percent of white Catholics voted for the GOP, and that nudged up just slightly to 59 percent in 2016.

For mainline Protestants, the vote in 2008 was nearly evenly split, with John McCain receiving a slim majority of votes (53%). Mitt Romney did slightly better four years later (55%). Trump enjoyed slightly more support from white mainline Protestants in 2016 (58%).

What do these patterns tell us about potential outcomes for 2020? Polling during the spring and summer of this year—during the uncertainty of the coronavirus pandemic—indicated that President Trump may be in a weaker electoral position this time.

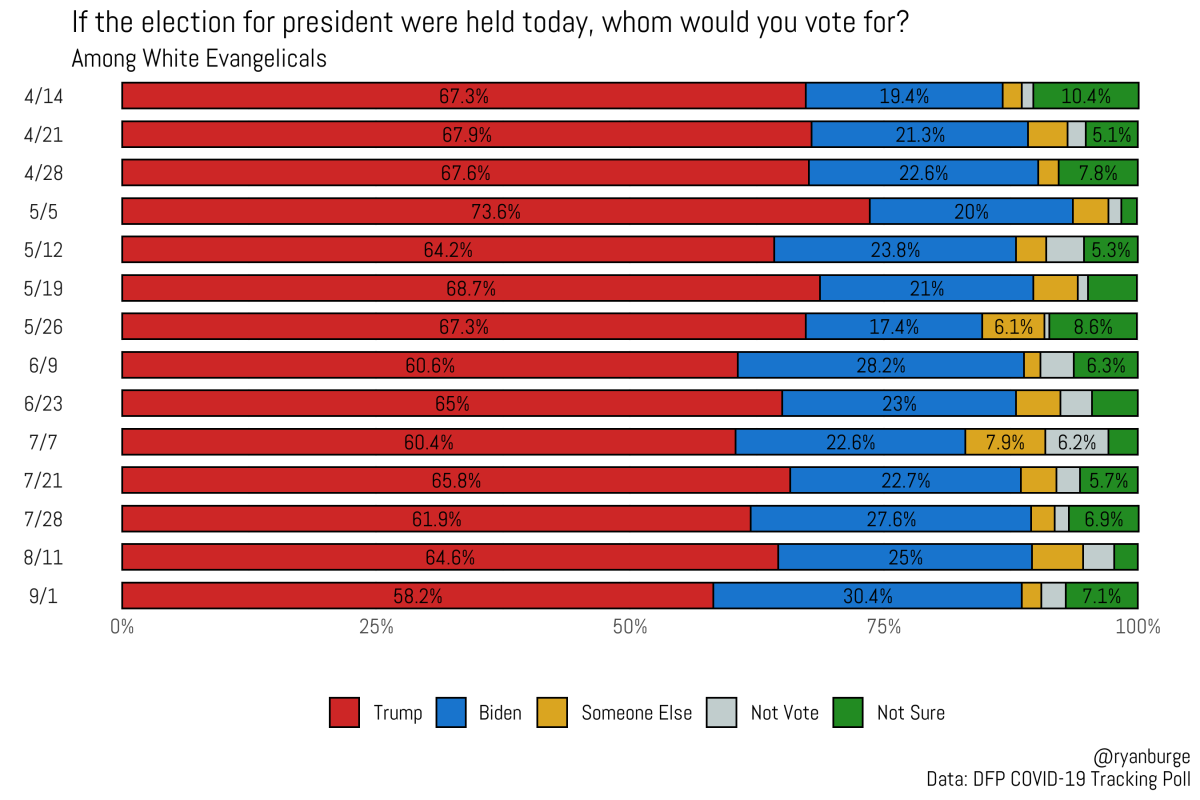

Based on weekly survey data collected by Data for Progress, then broken down by Christian traditions, we see white Christian support for the president slipping. Across traditions, slightly fewer Christians say they plan to vote for Trump and slightly more say they plan to vote for Biden than five months ago.

According to the Data for Progress survey, Biden’s share of the evangelical vote hovered around 20 percent in April and May, right in line with Clinton’s share four years ago. Trump’s support was around 70 percent, with about 15 percent of the sample saying that they were undecided or expressing the intention to vote for a third-party candidate.

However, support for Biden edged up during July and August to around a quarter of white evangelicals intending to vote for the Democratic challenger. The most recent data (collected on September 1) shows that Biden has as high as 30 percent of the white evangelical vote, a significant uptick from Clinton’s result in 2016 of just 19 percent.

If the trends hold, it appears likely that Trump may end up receiving 75 percent of the white evangelical vote, or possibly even less if those who are undecided break toward Biden in the last several weeks of the election cycle.

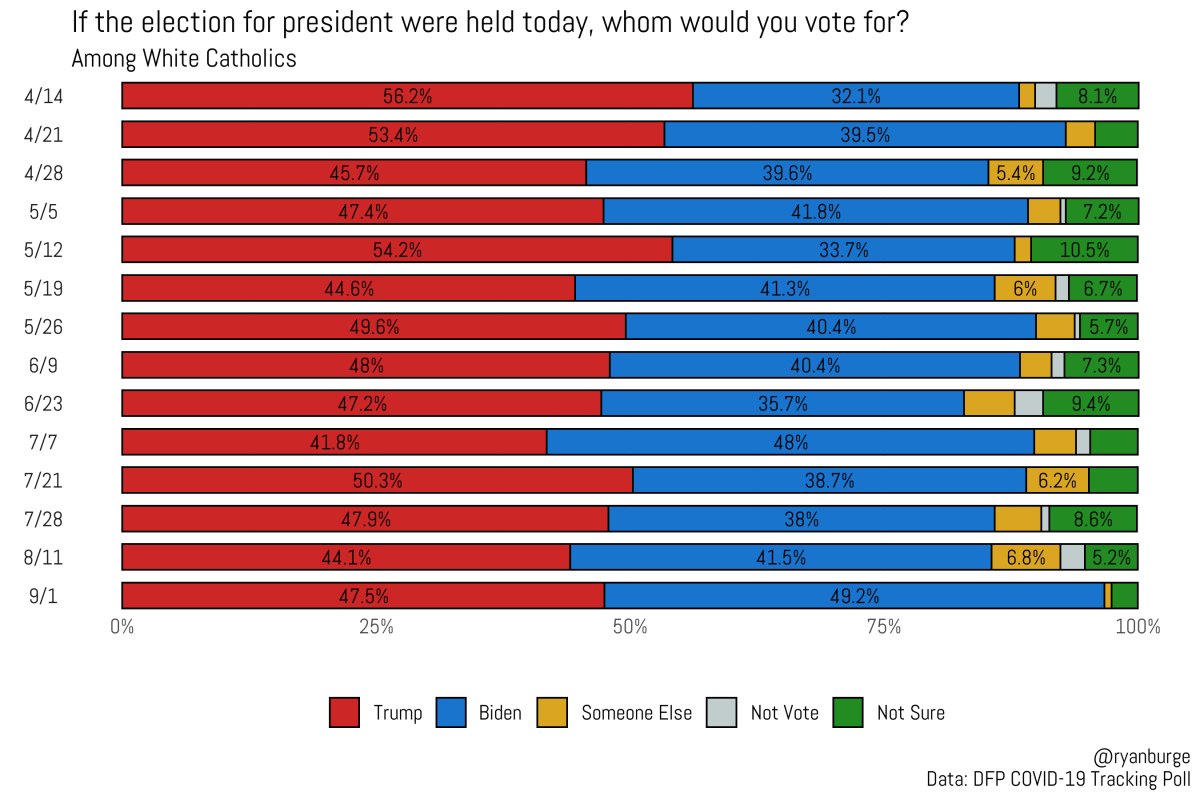

If the results for white evangelicals are slightly worrisome for the Trump campaign, the polling of white Catholics is a much louder alarm bell.

The president received 59 percent of this constituency in 2016, and in the spring it seemed likely that Trump would repeat that result in his matchup with Biden. In most waves of the survey, the president polled around 50 percent, while Joe Biden’s support was around 40 percent and another 10 percent were undecided or voting for a third party.

The poll conducted in September indicates a sharp shift among white Catholics: Biden and Trump are in a statistical dead heat, with just 3 percent now unsure. Of course, this could just be a statistical aberration, but this shift toward Biden in September appears for both white evangelicals and white Catholics. It’s more dramatic among the Catholics, a jump of nearly 8 percentage points.

With so few undecided voters in the sample, it seems very likely that the white Catholic vote may be closer to 50-50 in 2020, a huge shift from the 18-point margin Trump won in 2016.

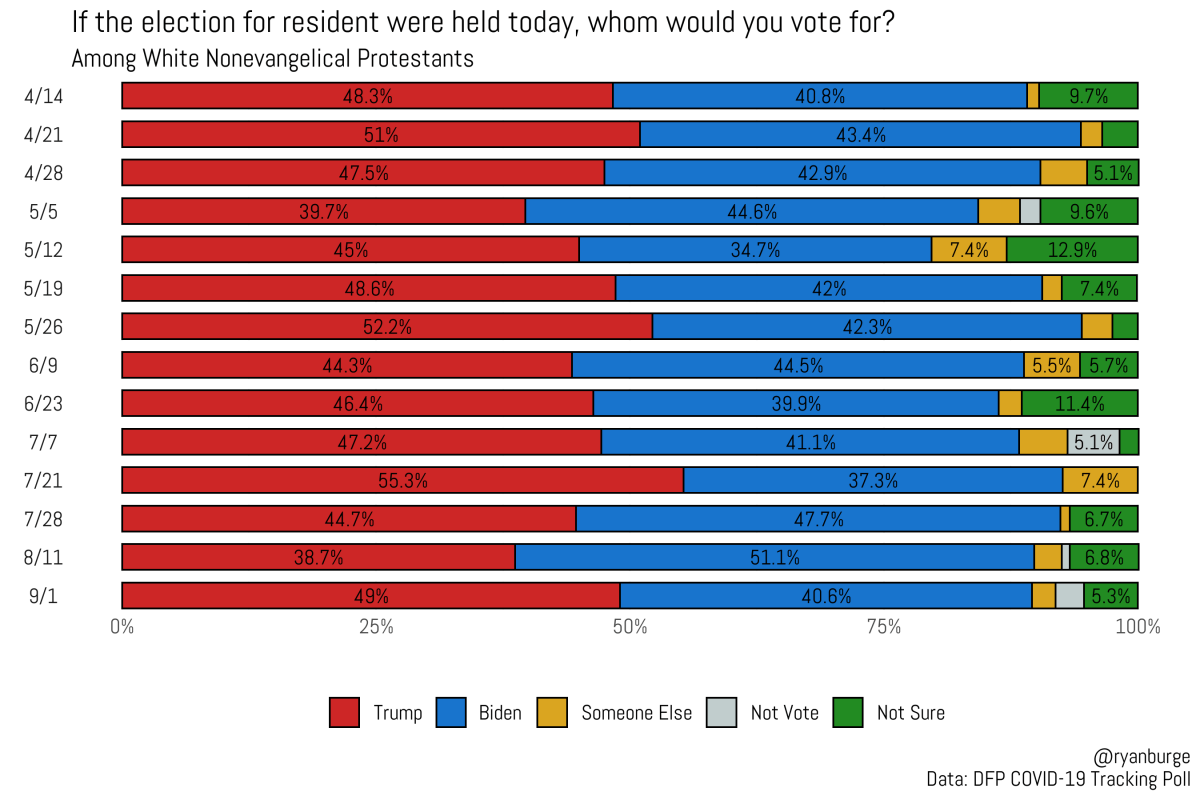

The results for white nonevangelical Protestants—comparable to the mainline Protestant data from the earlier elections—seems to show fairly similar results to the 2016 race. Clinton received 41 percent of this voting bloc, and Biden appears to be on track for around the same.

On average, Trump is hovering around 47 percent, while Biden is at 42 percent with another 10 percent undecided. It’s possible that the mainline vote will not deviate much from 2016.

Polling is an inexact science. It’s important to note that data from other polling firms shows that the votes of religious groups in 2020 look almost exactly like they did in 2016. But some state-level polls are reinforcing the trend that white Catholics are slipping away from Trump.

For instance, Marist found that among white Catholics in Pennsylvania, Trump was at 53 percent, while Biden was at 43 percent. In 2016, Trump beat Hillary Clinton among that group by 22 percentage points. In a state where white Catholics are a quarter of the vote, a 10-point swing among white Catholics should be enough to switch the state from red to blue.

For Trump to repeat his electoral victory in 2016, he is banking on holding together the coalition of voters that sent him to the White House four years ago. His opponent then did not engage in the level of faith outreach being conducted by the Biden campaign. But while Biden possibly picking up five points among white evangelicals would be noteworthy for observers of religion and politics, it wouldn’t be enough by itself to change the outcome of the election.

The Catholic vote, on the other hand, might. Biden, in part by virtue of his own religious background, may be well positioned to take nearly half of the white Catholic vote in 2020. If that pattern holds, the pathway to 270 electoral votes for the incumbent president becomes nearly impossible. The shift would also represent the most dramatic change in white Christian voting patterns in the last four election cycles.

Ryan P. Burge is an assistant professor of political science at Eastern Illinois University. His research appears on the site Religion in Public, and he tweets at @ryanburge.