A majority of American teens still follow their parents’ lead when it comes to religion. The trend holds whether families are religious or not—but it’s especially good news for evangelical Protestants, who care the most about their children sharing their beliefs.

Evangelical teens, like their parents, stand out as the most confident and active in their faith when compared to their peers, according to a new Pew Research Center report on the religious practices of 13-to-17-year-olds.

The religious makeup of today’s teens mostly resembles the population overall. About a third are “nones” (identifying as nothing in particular, atheist, or agnostic), the largest category. After that, about a quarter identify as Catholic and 21 percent as evangelical.

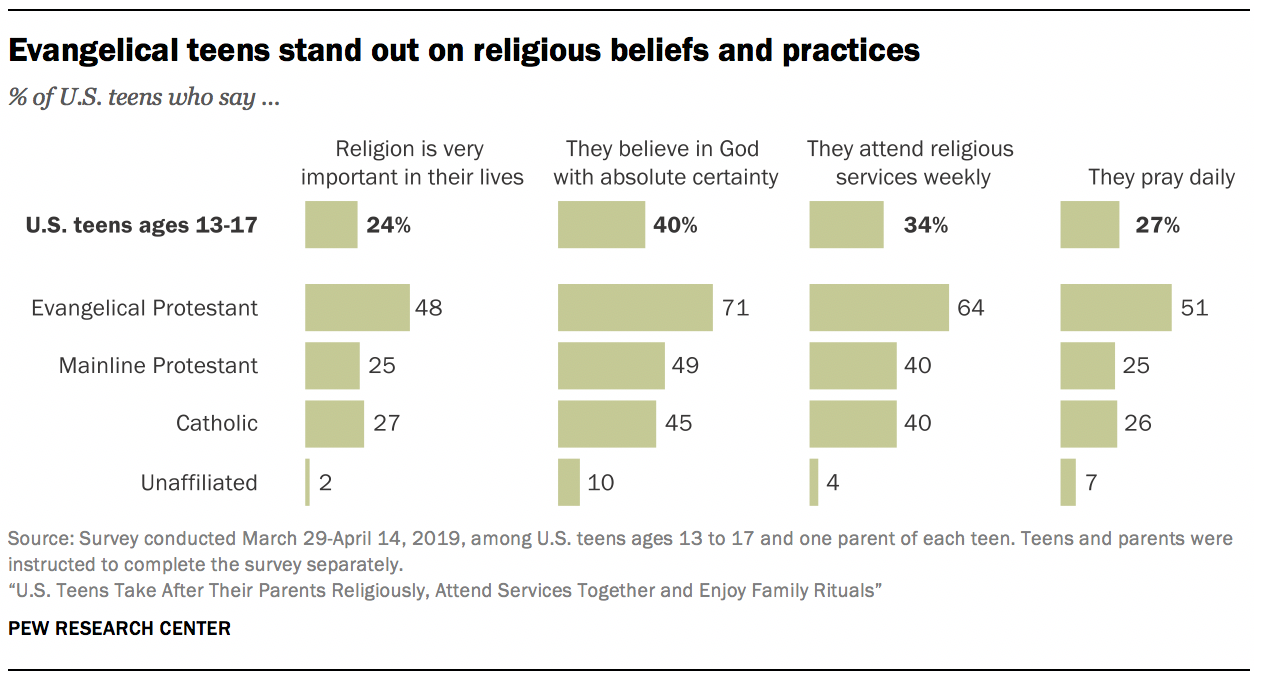

Even as teens, over half of evangelicals surveyed say they attend church at least weekly (64%), pray at least daily (51%), and belong to a youth group (64%), compared to a minority of teen respondents from other traditions. (It’s not just parental pressure. In the survey, two-thirds of evangelical teens say they attend church because they want to go, not to appease Mom and Dad.)

Family plays a big part in young evangelicals’ devotional lives. The vast majority say they enjoy religious activities with their families (88%), with 55 percent reading the Bible together, 80 percent saying grace at family meals, and 88 percent talking about religion, Pew found.

These practices correspond with a greater assurance in their religious beliefs. While nearly all teens who belong to a Christian tradition said they believe in God, 71 percent of evangelicals said they are “absolutely certain” in their belief, compared to just under of half of mainline (49%) and Catholic teens (45%). Evangelicals were also the only group among teens to agree that there is only one true religion.

But not all families fall on the same spiritual page once kids hit the teen years. Twelve percent of teens with evangelical parents don’t affiliate with a religion. Overall, about half of today’s youth say at least some of their beliefs differ from their parents, even if they still identify with the same tradition. The most common way teens see their convictions contrasting with Mom and Dad’s has to do with level of certainty: 14 percent say that they have more questions or are more unsure.

According to Pew, two-thirds of teens who don’t have “all the same” beliefs as their parents say their family knows about the differences, while a third say they don’t. Teens forming their own religious views and approaches as they grow up can be confusing for others under the same roof. Pew found that parents who misjudged their kids’ convictions were more likely to overestimate how important their faith was to them.

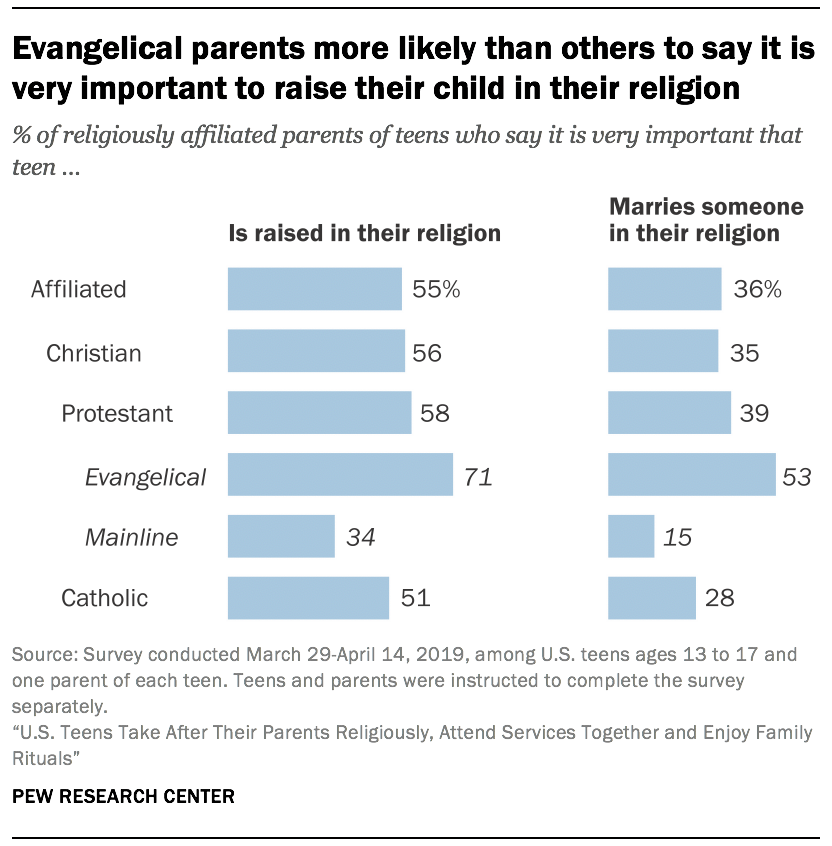

It can also be a sensitive topic for parents to broach. About seven-in-ten evangelical parents consider it “very important” to raise their children in their faith. They make it more of a priority than any other major tradition—half as many mainline Protestants say the same. But as much as they model their faith, surround them with Christian community, and pray for their kids’ salvation, evangelical parents also know their sons and daughters—God-willing, Spirit-empowered—will eventually have to come to understand the gospel for themselves.

CT asked parents of teenagers how important it is for their teenagers’ beliefs to align with theirs and how they approach the children’s faith at this stage. Here are their responses.

Dorena Williamson, speaker, author, and co-founder of Strong Tower Bible Church in Nashville:

I approach my kids’ faith with an understanding that it is not easy growing up with parents who work vocationally in church. I too was a PK (pastor’s kid) and know authenticity is key. I look for ways to encourage their faith in the atmosphere set at home. I always pray over them, seek out music they enjoy, and form conversations about current issues important to them. Hopefully, this communicates that I care about their interests. I don't expect my kids’ faith journey to mirror my own. These times hold new challenges and possibilities, and they have their own path to walk. At this stage in their spiritual lives, I pray they love God wholeheartedly and seek to love their neighbor. I know that is pleasing to God and a legacy that will endure.

Beth Felker Jones, professor of theology at Wheaton College:

My biggest prayer for my older kids is that they would love Jesus and throw their lives in with him. I don’t believe this is something I can control, because it can only come as a gift, but I pray for it and try to make way for it by talking with them about faith and making sure they have a strong group of adult Christians in their lives. I expect my teens to come to church and youth group, to pray with our family, to read Scripture. I hope they can talk freely with me and their father about questions of faith.

I don’t think parents can turn kids into our clones, and when it comes to nonessential matters, I try to hold very lightly any hope that they would perfectly agree with me. If they become adults who live with and for Jesus, my prayers would be answered, and I would do my very best not to obsess about whether they go to a different kind of church than I do or have different beliefs about what baptism means. And this is something I try to communicate directly to my teens: I don’t hope to make them like me. I do hope they’ll love Jesus and become like him.

John Starke, lead pastor at Apostles Church Uptown in New York:

Often when we talk about wanting our kids to align their beliefs with ours, that means a kind of cultural form of beliefs, rather than a biblical faith, and it tends to be a cloistered faith, rather one of understanding. At the same time, we believe in a heaven and hell, that God calls for repentance, and that our culture seduces us towards disbelief and rebellion. My hope is that they are given mercy and experience grace through faith.

We want them to understand our faith, recognize its cultural counterfeits, but also sense the freedom to ask difficult questions and fumble through “trying the faith on” as they grow up. I would want my kids to feel that they share our faith in common, since that would probably feel most secure and safe for them as individuals as they mature and grow into their own identities apart from us and as they grow and form their own faith in Christ.

Jen Michel, author of Surprised by Paradox, Keeping Place, and Teach Us to Want:

We’ve wanted to give our children the richest Christian formation possible in our home, and of course we’ve done that imperfectly. But as our children now leave home, one-by-one, we realize that the faith they take with them must be theirs, not ours.

I was just writing a very belated graduation letter to my 17-year-old son (soon to be 18). He would not call himself a Christian, and that’s very hard. I want him to know the reality of Jesus, but I also fully believe that he needs more than an inherited faith. By contrast, our daughter, now a sophomore in college, is walking with Jesus and serving in ministry on her college campus. That’s been a great joy, and we thank God.

Melissa Cain Travis, assistant Professor of apologetics at Houston Baptist University:

I consider it a particularly positive sign when my teenage sons raise theological disagreement with me; it means they're thinking deeply and critically about Christian doctrine! This is far better than disinterest, and it sparks rich (and sometimes very long) conversations in which I am able to demonstrate intellectual respect for them while offering gentle guidance.

I work to foster a mere Christianity ethos in our discussions but make it clear that secondary theological issues deserve careful consideration. It truly pleases me when my sons arrive at different yet well-thought-out conclusions on the non-essentials. In those instances, I simply make sure that they understand the merits of my perspective.

Kara Powell, executive director of the Fuller Youth Institute:

My kids’ relationship with Jesus is very important to me. As the mom of a 19-, 17-, and 14-year-old, most days I pray more for their faith than anything else. To be honest, a big part of me wants my kids to believe like me and worship like me (and vote like me, eat like me; the list could go on and on). But when I peel back the layers, what I ultimately long for is that my kids will know Jesus loves them and will love him in return. I want them to know that Jesus offers the best answers to their questions of identity, belonging, and purpose.

As our kids are owning their faith, the way they experience God’s love, and express their love in return, already looks different than mine. Based on research for our book Growing With, I try to ask each of my kids two questions: “What do you no longer believe that you think I do?” And, “What do you now believe that you think I don’t?” I want us to be able to discuss anything about Jesus and faith, especially when we disagree. With our two high-school-aged daughters … they’re more progressive on a handful of cultural issues and even more passionate about justice. When those differences emerge in our conversations, I’ve intentionally suggested, “When you’re older, you might want to look for a church that reflects what you believe.” Ultimately, I want my kids to love the church, not my church.

Amy Whitfield, host of SBC This Week and an associate vice president with the SBC Executive Committee:

Our shared faith in Christ, along with involvement in our local church, is incredibly important in the life of our family. As our teenagers have grown older, discipleship is definitely part of our parenting, but the role that faith plays in our relationship does change. When they were younger, we took a very proactive leadership role, standing out in front and systematically pointing them to the truths of the gospel. Now, as they grow spiritually, we are beginning to walk alongside them as older brothers and sisters in Christ, encouraging their personal study of the Bible and helping them understand and apply it to their lives.