While researching my upcoming book, I discovered, to my surprise, a white evangelical theologian who attended, and later pastored, a predominantly African American church in Pasadena, California. Paul King Jewett belonged to Scott United Methodist Church while a theology professor at Fuller Theological Seminary from 1955 to 1991. Learning about Jewett, I wondered, why don’t more white Christians attend predominantly black churches?

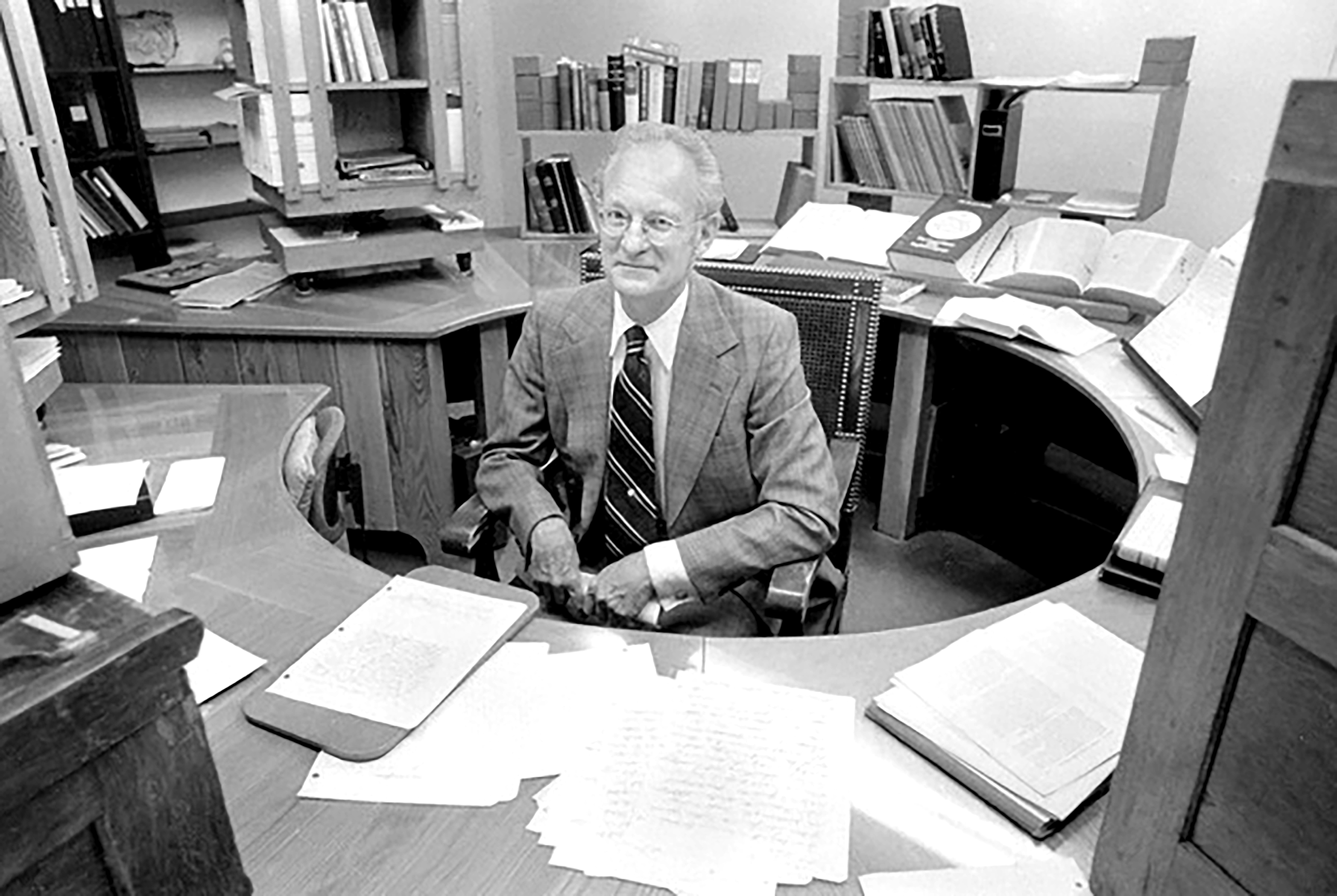

Courtesy of Fuller Theological Seminary

Courtesy of Fuller Theological SeminaryJewett, a renowned moral theologian, possessed a passion for promoting racial solidarity. He attended a predominantly black church, mentored black students at Fuller, became the first white board member of the National Negro Evangelical Association (currently known as the National Black Evangelical Association). He also attended the March on Washington in 1963 and the funeral of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968. Jewett was the epitome of a Christian bridge-builder. In a conversation with Ruth Lewis Bentley, widow of former National Black Evangelical Association president William H. Bentley, she recalled Jewett’s personal friendship with her husband and his interest and active involvement with African American social justice efforts. Bentley even reflected upon Jewett’s extended stay in their home on a visit to Chicago’s west side.

Jewett recognized the biblical devotion that informed King’s efforts to lift up the poor and socially disenfranchised. Jewett’s commitment to racial equality was contrary to the racial barriers prevalent within his own evangelical tradition. As evangelical theologian Carl F. H. Henry expressed in his 1947 work, The Uneasy Conscience of Modern Fundamentalism, “If the Bible-believing Christian is on the wrong side of the social problems such as war, race, class, labor, liquor, imperialism, etc., it is time to get over the fence to the right side. The church needs a progressive Fundamentalism with a social message.”

Many white Christians bought into the wrong-headed idea of segregated worship as sanctioned by God. Antebellum white Christian enslavers regulated the preaching content over the enslaved. Messages like “Slaves, obey your masters,” “Love your enemies,” and “Do not steal” served as biblical pretexts along with conflated readings related to the so-called Hamitic curse in Genesis 9 and the runaway slave narrative in the letter to Philemon. Such readings promoted the enslavement of dark-skinned peoples. From post–Civil War through the Jim Crow era, legal mandates dictated worship divided by race.

Speaking about white American Christians regularly attending church, Daniel Schultz notes that, “. . . as white American Christianity contracts, the people left behind in the pews are indeed those most committed to preserving the social order.” Keeping their churches alive requires preserving outdated traditions that promote social rigidity and racial resentment conditioned from the past. Many white churches situate residentially in white communities and draw their membership from there. Passé social attitudes go unchecked and unrecognized. Evangelicals have long sidestepped responsibility for advancing racial equality and solidarity. Edward J. Carnell, the second president of Fuller, confessed his personal difficulty in choosing “to do the Christian thing” over “personal interest.” Decades since, many white Christians still choose personal interest (such as social privilege) over “the Christian thing” to do.

For some white Christians, resistance to changing harmful traditional attitudes is viewed as giving in to worldly secularism and political correctness. But it’s possible to adapt to growing social changes without dethroning the God of Scripture.

For some white Christians, resistance to changing harmful traditional attitudes is viewed as giving in to worldly secularism and political correctness. But it’s possible to adapt to growing social changes without dethroning the God of Scripture. For white Christians to align with black congregations necessitates their leaving largely homogenous residential churches, neighborhoods, and attitudes. Misperceptions creating roadblocks to racial solidarity include white Christians’ views of African Americans as less educated, hence socially and culturally inferior to whites, compelling most white Christians to reject the idea of submitting to African American spiritual leadership.

The small cadre of black leadership in white Christian fellowships ironically raises further suspicion about commitments to racial and social justice, what Cornel West characterizes as race-effacing leaders or race-distancing elitists. In an attempt to appeal to a large white constituency, West contends “this type of [Black] leader tends to stunt progressive development and silence the prophetic voice in the Black community.” West argues that despite these individuals being the only black representatives in exclusive white circles, they are not necessarily the best ones to espouse black America’s concerns.

Multiracial churches, congregations where no single racial or ethnic group constitutes more than 80 percent of the membership, are typically headed by white leaders. These churches have been reeling due to protests and racial unrest in response to the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and other young African Americans at the hands of police officers. Multiracial and predominantly white churches promoting “race neutral” positions or “post-racial” climates get singled out as creating ironic roadblocks to racial solidarity.

The racial and ethnic divide within Christianity is akin to the first-century rift between Jews and Samaritans. Jesus’ encounter with a Samaritan woman at Jacob’s well, considered scandalous by his disciples and other Jews (John 4) exposed this division. Jesus engaged with the Samaritan woman at a deeper level beyond her gender and ethnicity, resulting in a spiritual liberation that brings forth reconciliation. Jesus confronted the status quo of Jewish-Samaritan ethnic division with his own privilege as a Jewish male teacher of the law. He aligned with this woman, serving as a bridge-builder of solidarity, reconciliation, and healing.

There are hopefully many white Christians who attend and align organically in solidarity with black Christian fellowships. Yet reconciliation must go beyond attendance and alignment. A majority of white Christians resist attending black churches or multiracial fellowships headed by African American leadership. Failure to cultivate racial solidarity misrepresents Christianity’s role in genuine reconciliation and healing. The life of Jesus, exuded by Paul Jewett, presses for deeper engagement, tapping into Christianity’s capacity as a bridge toward solidarity we all must be willing to travel.

Jamal-Dominique Hopkins is dean and associate professor of religion and theology at Allen University’s Dickerson-Green Theological Seminary. An ordained minister, he also is a Christ and Being Human Pedagogy Fellow at Yale University’s Center for Faith and Culture.