When Renca Dunn talks about having the Bible in her own language for the first time, she emphasizes the adjectives. In English, she has no problem understanding the people, places, and things of Scripture. But in her own language, the nouns vibrate with life and emotion.

“The clapping trees. The singing birds. The dancing meadows,” Dunn says. “The persistent Esther. The revengeful Saul. The weeping Magdalene. Most of all, our loving Jesus.”

With the translation of Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel in the fall of 2020, Dunn and 3.5 million other deaf people finally have the complete Bible in American Sign Language (ASL). It’s been a long time coming. The translation has been in the works since 1981, when Duane King, a minister in the Independent Christian Church, realized that English was not the heart language of deaf people in America. ASL was.

King, who is a hearing person, started learning to sign after meeting a Christian couple in 1970 who didn’t come to church much because they couldn’t understand what was going on. He and his wife, Peggy, were moved to meet this need and started a church and a mission for the deaf near one of the nation’s leading deaf schools in Council Bluffs, Iowa. Then, after years of church meetings, small groups, and Bible classes, the Kings became convinced it wasn’t enough to sign the English Bible; the Bible needed to be translated into ASL.

“Most hearing people don’t understand how difficult it is to learn to read what you cannot hear,” Duane King said in 2019. “Deaf people rely so much on their eyesight that they want everything to be tangible—they want to be able to see everything. This sometimes makes it harder to grasp intangibles like salvation through faith.”

The evangelical commitment to sharing the gospel with everyone is a commitment to accessibility. It took a long time for Christians to think about what that might mean for deaf people, though.

The first Braille Bible for the blind was finished in 1919, more than 100 years before the first complete Bible for the deaf. Braille is not a distinct language, but an alternative alphabet that can be read by touch. ASL, on the other hand, is not spoken English turned into hand signs but is a full language developed by deaf people, with a distinct vocabulary and grammar.

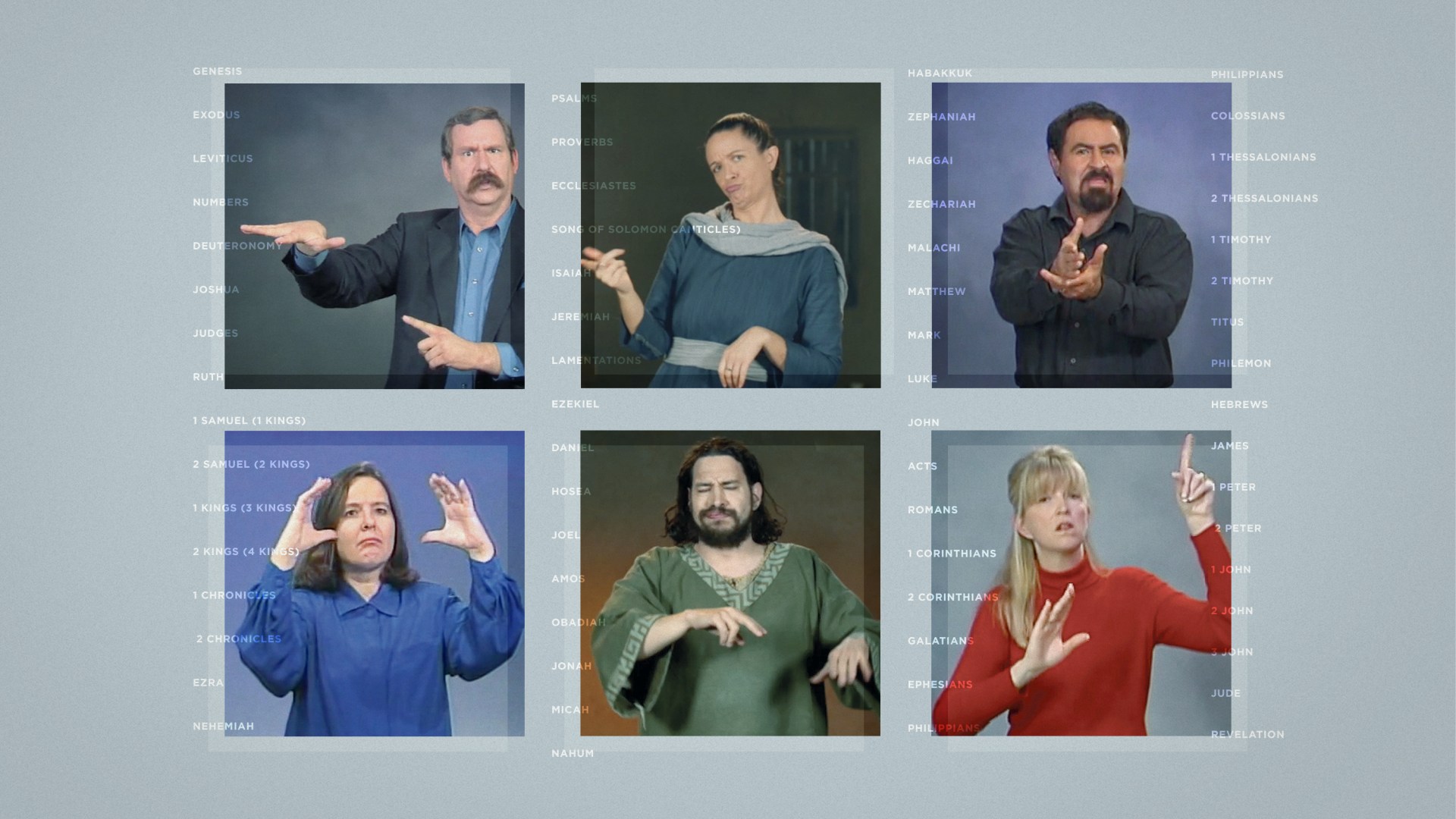

When the Deaf Missions Bible project started, deaf translators took the Greek New Testament, translated it into ASL, and recorded that onto VHS tapes. The tapes could be sent out in the mail. Nearly 40 years later, when deaf translators took the major prophets of the Hebrew Bible and translated them into ASL, they made the videos available for free online, through social media, and on a smartphone app.

The evangelical commitment to sharing the gospel with everyone is a commitment to accessibility. It took a long time for Christians to think about what that might mean for deaf people.

The translation was led by deaf people trained in the biblical languages, reviewed by one committee for accuracy and by another committee for clarity, and then recorded in a small TV studio. It cost $195 to translate a single verse. The last four years of work cost more than $4 million.

“It is a very comprehensive and very intensive process,” said Chad Entinger, who took over leadership of Deaf Missions when King retired in 2017. “Typically when we think ‘Bible,’ we think of a printed book. For us deaf people, the ASL Version is in video format because sign language is a visual language.”

The ASL Version is not the only modern effort to make Scripture available to the deaf. The Jehovah’s Witnesses finished translating their New World Translation into ASL earlier this year. The Witnesses—who do not believe in the Trinity and teach that Jesus is a distinct creation and not God incarnate—had their first sign language congregation in 1989 and started translating the religious magazine The Watchtower in 2002 and the Bible in 2005. The Bible project was completed when the Witnesses translated Job in March.

“We realized that ASL was the language of their hearts,” said spokesman Robert Hendricks. “ASL was the language and is the language that would bring them closer to their God Jehovah and get them to understand what he requires of them.”

There is also a complete New Testament in a written version of ASL called SignWriting, produced by ASL Gospel founder Nancy Romero. SignWriting is “almost hieroglyphic,” according to Anthony Schmidt, senior curator at the Museum of the Bible, who acquired an eight-volume copy of the SignWriting Bible for the museum. It includes arrows, circles, and lines that represent signing motions and facial expressions.

SignWriting was originally developed to notate dance moves. It was adapted for the deaf by Romero starting in the 1980s. The New Testament took her 10 years to complete. Though it’s not widely used, according to Schmidt, it is an important artifact for the museum.

“It represents this broad effort to reach all people,” he explained. “It shows the passion that a lot of Christians have for translation and the calling they feel to provide access to the Bible.”

The ASL Version of the Bible—produced by Deaf Missions with support from the Deaf Bible Society, DOOR International, Deaf Harbor, the American Bible Society, Wycliffe Bible Translators, Seed Company, and Pioneer Bible Translators—is the first sign language Bible to be translated from the original languages. Erle Deira, a project manager at the American Bible Society, said it is also the first to be accepted as authoritative by Protestants worldwide and will be used to assist in translating the Bible into other sign languages, including Nigerian, Japanese, and Mexican.

“We are very grateful that we have sufficient Biblical scholars who understand Greek, Aramaic, and Hebrew who are part of the deaf community,” Deira said. “It was important that deaf people who are trained to be translators, those are the people who call the shots. Those are the people who decide how to best express an idea from Hebrew. They have ownership.”

Fifty-three translators have worked on the project since 1981. Renca Dunn became one of them. For her and many others, that work meant seeing the Bible come alive and experiencing a deeper, more intense relationship with God.

“When I see the Bible in sign language, I finally feel that God does get me,” Dunn said. “He understands me. He wants me to understand him. He loves me. He wants me to love him. He speaks in my language.”

Daniel Silliman is news editor for Christianity Today. Additional reporting by Taylor Bundren.