Several years ago, I sat on the top floor of World Vision’s nine-story office building on Yeouido Island in Seoul, South Korea. It was located blocks from the National Assembly and was dwarfed by soaring skyscrapers in the nation’s main political and financial district. The real estate was elite. The building, befitting a humanitarian nonprofit organization, was not. I interviewed a series of Korean executives over bottles of orange juice, surrounded by sturdy vintage furniture from the 1970s.

I had traveled to Korea to research the origins of World Vision, one of the largest humanitarian organizations in the world. I was expecting to confirm the accepted narrative of a dynamic evangelist named Bob Pierce, who in 1950 was undone by the sights of Marxist cruelties in Seoul. Working alongside the US Army, Pierce started schools, orphanages, and churches that helped lift Korea to capitalist heights out of wartime devastation. The myth of World Vision’s founding—an altruistic American evangelical organization born in the anxious ferment of the Cold War—has stood for well over a half century.

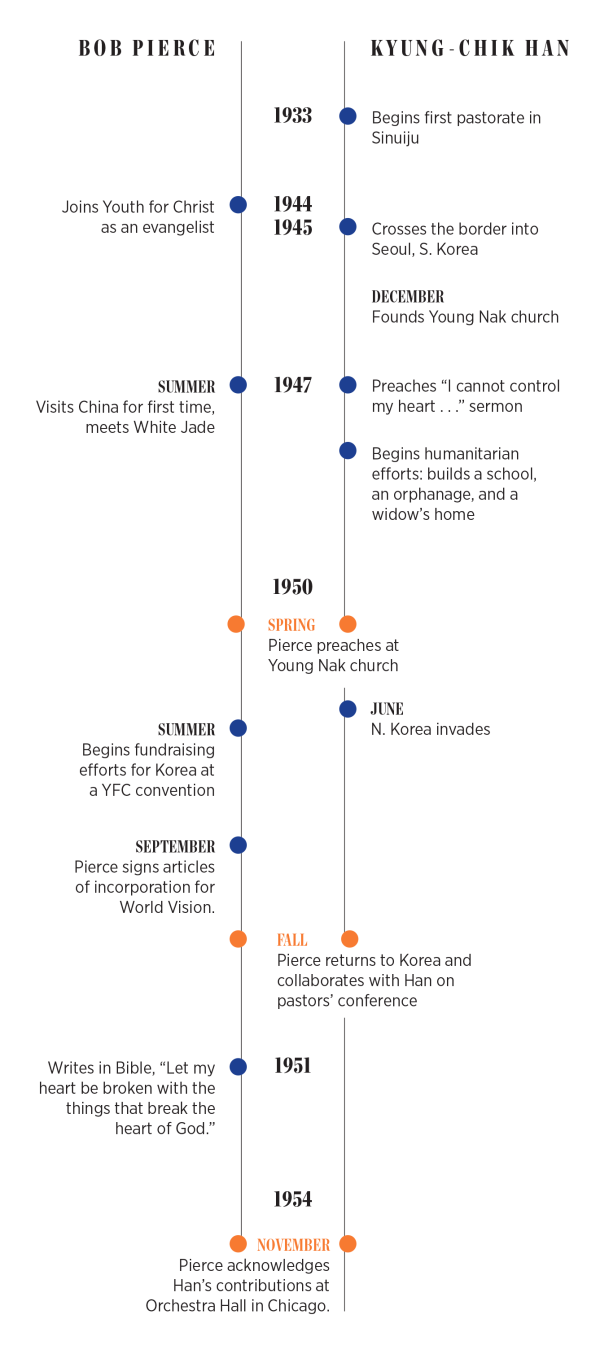

As I talked with Jong-Sam Park, the just-retired president of World Vision Korea, he jolted me out of this conventional narrative. The distinguished, silver-haired executive fielded my persistent questions about Bob Pierce, but he wanted to talk much more about a Korean pastor I had never heard of. Kyung-Chik Han had helped Park during the Korean War when he was a homeless refugee child covered only by a straw mat as he slept on the streets of Seoul.

I listened impatiently, hoping to return to my questions about American missionaries. But when I tried to guide him back, he grew exasperated. Han, he explained, was also a founder of World Vision. “World Vision Korea?” I tried to clarify. “No, the whole thing,” he replied.

Upon reflection, Park’s assertion fit evidence that I had previously overlooked. I had seen several photographs in which Pierce and Han appeared on stage together, usually with a caption describing Han as Pierce’s “interpreter.” Indeed, many archival sources from the early 1950s described the two men appearing together, most often in Seoul. Han may have interpreted Pierce’s sermons into Korean for his parishioners, but Han also spoke in his own voice as the pastor of the largest Presbyterian church in the world—and as the architect of hundreds of humanitarian initiatives that were becoming the foundation of World Vision.

As Pierce became a legend, friend to presidents around the world and the recognized founder of World Vision, Han was ushered off the stage, disappearing from American consciousness.

There were also clues in America about Han’s contributions. On one cold November evening in 1954 in Chicago’s Orchestra Hall, where Han earlier had appeared on stage, the irrepressible Pierce acknowledged his colleague’s evangelistic and humanitarian bona fides. Han, he said, was expertly distributing rice and the gospel to “war weary” Koreans. In this moment, a terrifying time in the Cold War when it appeared as if the United States and the Soviet Union might destroy each other with nuclear weapons, Pierce proclaimed hope for Asia, partly because of Han’s work on the Korean peninsula. Pierce called him “a man of God, full of the Holy Ghost, the real soul-winner.” But Pierce didn’t put all his hope in Han—or in God. He praised American bombers over Seoul, and he pledged to do his part. “I don’t expect to die in hospital sheets, I expect to die at the hand of a Communist.”

Pierce ended his sermon with a combination sales pitch–altar call:

How I pray tonight that there will be someone who will answer the call and give God your heart, to fill you with the Holy Ghost, and break your heart. . . . I have 600 children waiting [for] adoption this month. Their pictures are already taken, their names [could be] filed within ten days, if you will write on that envelope “I will adopt a child” and covenant with God that you will send ten dollars a month for a year.

With businesslike efficiency, ushers collected the pledges, moved the crowd out, and brought in a new one. Then Pierce gave the presentation all over again.

The money collected in Chicago went to a brand-new organization called World Vision. Like Billy Graham and growing evangelical institutions such as Youth for Christ and Christianity Today in the 1950s, World Vision nurtured a strong dedication to spiritual revival and a strong opposition to communism. What made it different was its emphasis on humanitarian relief. But this too was attractive to many American Christians, who propelled World Vision to prominence. The ministry grew from 240 sponsorships of children in 1954 to 1 million in 1990 and 3.5 million by 2015.

Today the recipient of multimillion-dollar grants from the US government and millions of small donations from individuals, World Vision is the 19th-largest charity in the United States by private donations. The American arm records annual revenues of more than $1 billion; combined revenues for World Vision International, the global umbrella organization, are $2.75 billion.

But 65 years ago in Orchestra Hall, the notion that World Vision was the brainchild of two men was already starting to fade. As Pierce became a legend, friend to presidents around the world and the recognized founder of World Vision, Han was ushered off the stage, disappearing from American consciousness.

An American Narrative

Pierce moved to Southern California in the 1930s, along with many other Americans devastated by the Great Depression. Dramatically converted to faith, he overcame an unstable childhood and a rocky marriage and began to preach salvation with the passion of a man who had radically experienced it himself. His charisma took him on a fast track through the surging Sun Belt evangelical world of Southern California Baptists, Nazarenes, and the Christian and Missionary Alliance. After serving at several churches as a youth leader and associate pastor, Pierce became an evangelist with Youth for Christ.

Pierce’s first international trips to China in the late 1940s fueled his anticommunist convictions. After notching 17,852 “decisions for Christ” during a stunningly successful evangelistic tour, he witnessed the destruction of hospitals, schools, and missionary compounds by the Red Army. Chinese pastors—new friends of the American evangelist—were murdered. Pierce, sometimes only miles from the front, barely escaped before Mao Zedong took all of mainland China. The specter of communism had turned into a ghastly spectacle.

With China lost, Pierce set his sights on Korea. But an early 1950 visit reinforced his sense of alarm. Russian forces lay across the 38th parallel, and just weeks after Pierce returned to the US, North Korea invaded. The attack, which sparked the Korean War, immediately engulfed Seoul and pushed the South Koreans to the southern coast. By September 1950, communists held more than 90 percent of the Korean peninsula.

A daring intervention at Incheon in November by General Douglas MacArthur, however, led to the recapture of Seoul. In fact, US and United Nations forces advanced northward all the way to the Yalu River on the border of Korea and China. Then the tide turned again. The sudden insertion of Chinese Communist forces reversed the progress, leaving Seoul once again, in Pierce’s description, a “bleeding, battered city.” And the war continued, going back and forth until 1953, when an armistice established a demilitarized zone at the same line at which the hostilities had begun three years earlier.

In Korea, as in China, Pierce’s work emerged as an existential response to communism. Pierce maintained a frenetic pace in those years of military action. At first watching helplessly from his home base in the United States, he began raising money for one of the first hot fronts of the Cold War. At a 1950 conference in Winona Lake, Indiana, Pierce told dramatic stories of Christian martyrdom as he pleaded for generous gifts. Billy Graham, who spoke after Pierce, told the crowd, “I had planned to buy a Bel Air Chevy, but instead I’m giving the money to Bob Pierce for the Koreans.”

On the spiritual front, Pierce continued an evangelistic offensive. In the midst of war, he persuaded 25,000 Korean civilians, Korean soldiers, and American soldiers to “turn from the darkness of heathenism and unbelief unto the glorious light of the Gospel.” South Korea’s President Syngman Rhee, a Christian, effusively praised Pierce’s successes. Pierce relayed in a newsletter that Rhee believed “Youth for Christ’s type of evangelism will help hold back the flood of atheism which is flowing through the Far East.”

If Pierce’s combination of wanderlust and revivalism was not unusual, his response to the suffering was. Though evangelicals had long built hospitals and schools around the world, the fundamentalist-modernist controversies of the 1920s had moved evangelicals, at least rhetorically, away from work that smacked of the social gospel. Pierce’s encounter with physical suffering and poverty in China and Korea, however, provoked him to reengage with humanitarian efforts both theologically and rhetorically.

Pierce’s humanitarianism was awakened through a personal encounter that became the myth of World Vision’s founding. He met a young Chinese girl named White Jade who had been beaten and disowned by her father after she converted to the Christian faith. Effectively an orphan, White Jade had no place to go. A local missionary did not have the capacity to care for yet another orphan. Pierce gave the missionary and White Jade all his remaining cash—five dollars—and pledged the same amount each month thereafter.

This encounter, among others, so moved Pierce that he wrote a sentence on the inside cover of his Bible: “Let my heart be broken with the things that break the heart of God.” This became World Vision’s mantra, and it birthed its child sponsorship program. American evangelicals could sponsor a Korean orphan for ten dollars a month to help with food, clothing, education, and religious teaching. Funds for “my orphanages,” as Pierce called them, jumped from $57,000 to over $450,000 between 1954 and 1956. By the late 1960s, World Vision had become a humanitarian behemoth familiar even to nonreligious Americans. As historian David King has shown, it patched together “the dichotomy between evangelism and social action that had ripped apart the Protestant missionary enterprise.” Pierce, it seemed, was the force of nature that set it in motion.

That’s the official World Vision history. But from Korea itself, there is another narrative, one that pushes back against a triumphalist American storyline and features Korean Christians influencing Americans.

A Korean Story

Han’s rise to prominence was even less likely than Pierce’s. Born to a Confucian family in 1902, Han grew up in a small, poverty-stricken village 25 miles north of Pyongyang. Revival swept through the area in the years around Han’s birth, and his family, along with many others, converted to Christianity. It is difficult to imagine now, but before Pyongyang became the capital city of an atheistic North Korea, it was the spiritual capital for all of Christian Asia.

Han himself was a very impressive young man. Church leaders, noting his amiable personality, exceptional intelligence, diligent work ethic, and vital faith, quickly identified his potential. Benefactors sent him to study at Princeton Theological Seminary with noted theologian J. Gresham Machen. Compelled by Machen’s intellect and theology but unimpressed by his pugnacious fundamentalism, Han occupied a middle theological space characterized by a gentle and ecumenical conservatism.

These qualities served Han well during his first Korean pastorate in Sinuiju, a large city at the border of China. If Pierce’s social concern was built on the intensely emotional response of a privileged American’s shock at foreign poverty, Han’s was rooted in the prolonged shepherding of a suffering flock. His 13 years in the far north of Korea were a productive if worrisome time, as his congregation dealt with profound social problems. Increasing Japanese imperialism was restricting Christian activities. His church suffered from a struggling economy, and there were few political freedoms. At one point, Japanese authorities, having tortured Han, forced him to bow to a Shinto shrine, an act he regretted for the rest of his life. Amid these difficulties, he nonetheless oversaw the construction of a church building, an orphanage, and a nursing home. Han was emerging as an important voice in religious and civic affairs.

Han’s rising prominence became most evident when Japan surrendered to Allied forces at the end of World War II. Han was tapped by the Japanese governor-general to oversee security during the transition. He established the Sinuiju Self-Government Association, which organized young men in policing efforts. But Han’s exhilaration at the overthrow of Japan gave way to despair. American rule in the north of Korea did not materialize as he had expected. Instead, a North-South boundary was established at the 38th parallel along with Soviet oversight of Sinuiju. The communists immediately cracked down and subjected millions to land seizure, torture, and summary executions. When an order was issued for his arrest, Han disguised himself as a common refugee. He managed to cross the border into South Korea, which was still leaky in late 1945.

Han’s leadership blossomed in Seoul. Exacerbated by a crush of refugees from the north, conditions were as bad in Seoul as in Sinuiju. Han was driven to despair as he walked among beggars, the homeless, and prostitutes. “I cannot control my heart,” he mourned in a sermon titled “A Gospel of the Propertyless.” “I cannot lift up my head, so that bending my head and walking became my habit.” Immediately he began securing tents, organizing refugees into cooperatives, assigning work duties, and establishing schools. In December 1945, he presided over the first meetings of 27 refugees at Young Nak Presbyterian, called the “refugee church” because of its predominate membership of displaced North Koreans. Within half a year, the church claimed 1,000 members. Within two years, it tallied 4,300.

For four years, these refugees held services in tents. Then, through Han’s connections in the United States, Young Nak raised $20,000 the refugees used for materials to build a giant stone Gothic structure by hand. All the while, Han continued his humanitarian work. In 1947, he began half a dozen new projects, including several orphanages, a widow’s home, more schools, and a funeral home. In 1948, he worked to get North Korean refugees voting rights. “To help the poor and the weak people must be the first,” declared Han.

On June 25, 1950, tragedy struck yet again. Just weeks after Young Nak completed its church building, North Korea invaded. The numbers of the poor and weak multiplied as both sides committed atrocities. One church leader was executed at Young Nak’s gate for denying entry to the invading forces who wanted to use the church as an armory. Reports circulated of 3,000 Christian pastors who were drowned in the Han River by communist forces. Within months, nearly the entire peninsula was razed.

Han’s humanitarian work accelerated in the chaos. One day after the war began, he launched the Korean Christian National Relief Society. He also led the Christian Union Emergency Committee for War. He negotiated with General MacArthur for tents from the US Army and distributed them in refugee camps. That Han served as a South Korean delegate to the United Nations in March 1951 underscores his status as a consummate insider who brokered high-level humanitarian deals. Han was a bureaucratic force of nature as he led dozens of Korean organizations.

Observers, trying to explain his organizational genius, noted that he was an unassuming leader whose quiet charisma gave his colleagues “inspiration and encouragement” to follow his lead. Others called Han a master mediator who could bring about consensus through gentle persuasion. He was also brutally efficient, working doggedly to produce the best results. One onlooker quipped that Han operated like a rational businessman “even though he claimed to just be an old servant of God.”

Facing West

Bob Pierce’s “rescue” of Korean Christians—and the West’s portrayal of his relationship with Han, the “exotic interpreter”—looks very different facing west rather than east. Before Pierce ever set foot in Korea, the foundation had already been laid for the construction of World Vision. Han, a distinguished churchman fluent in English, was already coordinating relief work and networking with contacts all over the world.

American evangelicals never narrated it this way, but it might be accurate to say that Han discovered Pierce as much as Pierce discovered Han. It was Han who in early 1950 invited Pierce, at an American missionary’s advice, to speak at Young Nak Church. Quickly discerning that Pierce could contribute to the humanitarian projects he had founded, Han hosted the evangelist the very night he arrived in Seoul. Pierce recorded that he preached to 1,500 congregants “huddled together in one great mosaic of human flesh,” and Han followed up on this new relationship almost immediately by inviting Pierce to preach at a large open-air revival in Seoul.

Sometimes, the interpreter is much more than an interpreter.

When war broke out just weeks later, Han kept Pierce apprised of conditions. In late 1950, they met again in Busan, South Korea, and worked together to hold a series of pastors’ conferences. At the culminating event, Pierce was the main speaker, and he paid for the entire conference. Han certainly interpreted for Pierce, as the Americans incessantly noted, but this did not mean he was the subordinate in the relationship. Han organized everything.

This collaborative arrangement became the pattern for the two humanitarians. Pierce spearheaded fundraising and publicity, and Han oversaw the infant ministries of World Vision. Most of these had been operational even before Pierce came on the scene. Under Han’s influence, their partnership increasingly took the form of social relief, work that became the heart of World Vision activity around the world.

Pierce was plugging into an already-existing humanitarian network constructed by Han. Before World Vision, there was Young Nak Church; before Young Nak Church there was Sinijui; before Sinijui there was a Christian family just outside Pyongyang. The genealogy of World Vision is profoundly Korean.

As the years passed, however, Han’s role in World Vision’s myth of origin diminished. A 1960 account by author Richard Gehman mentioned Han only briefly, as part of a Korean delegation that greeted Pierce at the Seoul airport. It credited Western groups for orphanage work. A 1972 tribute described Han as a devout saint and “a gentle, dedicated pastor” who built several orphanages and schools for refugees, but it included no acknowledgment that World Vision came directly out of Han’s activities before and during the Korean War. In 1983, Franklin Graham repeated the long-standing line that a “fine interpreter, Dr. Hahn [sic]” translated Pierce’s message “into understandable Korean.”

Man of Vision, a biography written by Marilee Pierce Dunker, Pierce’s daughter, acknowledged that Pierce “became involved with the Tabitha Widows’ Home, sponsored by the Yung [sic] Nak Presbyterian Church,” but nonetheless stated, “And behind every bit of it was the compassion, the energy, and the vision of one man; in fact, to most people World Vision was Bob Pierce.”

Despite Han’s continued involvement in both World Vision International and World Vision Korea, references to his legacy were overwhelmed by a triumphalist narrative of Western evangelical social action.

Pierce himself did not mean to obscure Han’s contributions. World Vision’s earliest literature offered descriptions of—and even glowing tributes to—Han. In his first memoir, The Untold Korea Story, Pierce effusively praised Han’s courage, piety, and prowess in serving his people. “Out of the chaos of the past,” wrote Pierce, “this man of God built a future for his people.” In an interview with CT, Dunker said her father “would be the first one to say, ‘I had the vision, but I didn’t do it. I was a fundraiser. I was the communicator. The people on the ground did it.’ ”

Nor did Han seem to resent Pierce as the rising star. Indeed, Han flew from Seoul to Los Angeles to preach at his colleague’s 1978 funeral, where he said, “The people of Korea can never forget him, for he was the best-known preacher of the gospel and welfare worker from abroad during the Korean War. . . . God be praised for him.” But Han’s qualifying phrase, “from abroad,” also testifies that Pierce was never the sole founder. Koreans have consistently portrayed World Vision as a collaborative enterprise of which Pierce and Han were cofounders. Pierce, says Park, the former World Vision Korea president, “was a master performer with a script. Koreans did 90 percent of it.” World Vision may have been incorporated in the United States, but a battered North Korean pastor actually built it in the slums of Seoul.

In a TED talk titled “The Danger of a Single Story,” Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Adichie describes how a dominant narrative can stereotype and ultimately disempower other actors. Many American Christians, understandably eager to enshrine the piety and progress of one of their own heroes, have done exactly this. The result has been a single, definitive story that emphasizes a strong, benevolent America and a needy, desperate Korea. To be sure, American money and technical expertise helped South Korea emerge out of utter devastation. Pierce was an important part of that. But the other story is that there was already a thriving Christianity, one that was arguably more vibrant than the American version, one that taught Americans about the value of fervent prayer, social relief, and development work. Sometimes, the interpreter is much more than an interpreter.

Transnational collaborations, like the one between Han and Pierce, are multiplying as faith moves in disorienting directions in this new century. More than two-thirds of the world’s Christians now live outside North America and Europe. And demographers forecast that the United States will become a majority-minority nation sometime in the 2040s.

Many American organizations, from Compassion International to InterVarsity to the National Association of Evangelicals, are anticipating the new realities and tapping Christians who look more like the majority world for positions of leadership. But it is also important to recognize that the shaping of faith-based institutions by people of color is not just a present and future reality. It is something that has been happening all along. It is time for mission agencies and humanitarian organizations to plumb their pasts in search of their own Kyung-Chik Hans. Who are the men and women lost to historical memory, or hidden all along, who have built Christian institutions across the globe?

For World Vision—which named Edgar Sandoval as its first nonwhite American CEO in 2018, internationalized its governance in the 1970s, and has featured a diverse constituency for half a century—this should be a natural move. Including Han in its founding narrative would much better fit what World Vision already is: a profoundly international and multiethnic organization.

There is evidence the narrative may, in fact, already be shifting. Forty years after writing her father’s biography, Dunker says she is writing her next book. It will feature Han’s story alongside those of other churches and individuals who laid the groundwork for World Vision to become the global powerhouse it is today.

David R. Swartz is an associate professor of history at Asbury University. He is the author of Facing West: American Evangelicals in an Age of World Christianity (Oxford University Press, April 2020).