By now, we’ve all heard about the rise of the “nones.” Every year there seems to be another round of survey data indicating that the religiously unaffiliated in the US have jumped another percentage point or two.

But some recent findings about Generation Z may challenge that narrative, suggesting that the share of the nones may be leveling off.

The oldest members of Gen Z were born in 1995, which means that they joined survey populations when they turned 18, starting in 2013.

It would be fair to assume that their level of religious unaffiliation should exceed that of the millennials before them, the same way millennials left religion in larger numbers than Generation X. But that assumption is not borne out by the data.

Although all age groups have increasingly stepped away from religion over the past decade, every generation except Gen Z showed significantly higher rates of disaffiliation than the ones before.

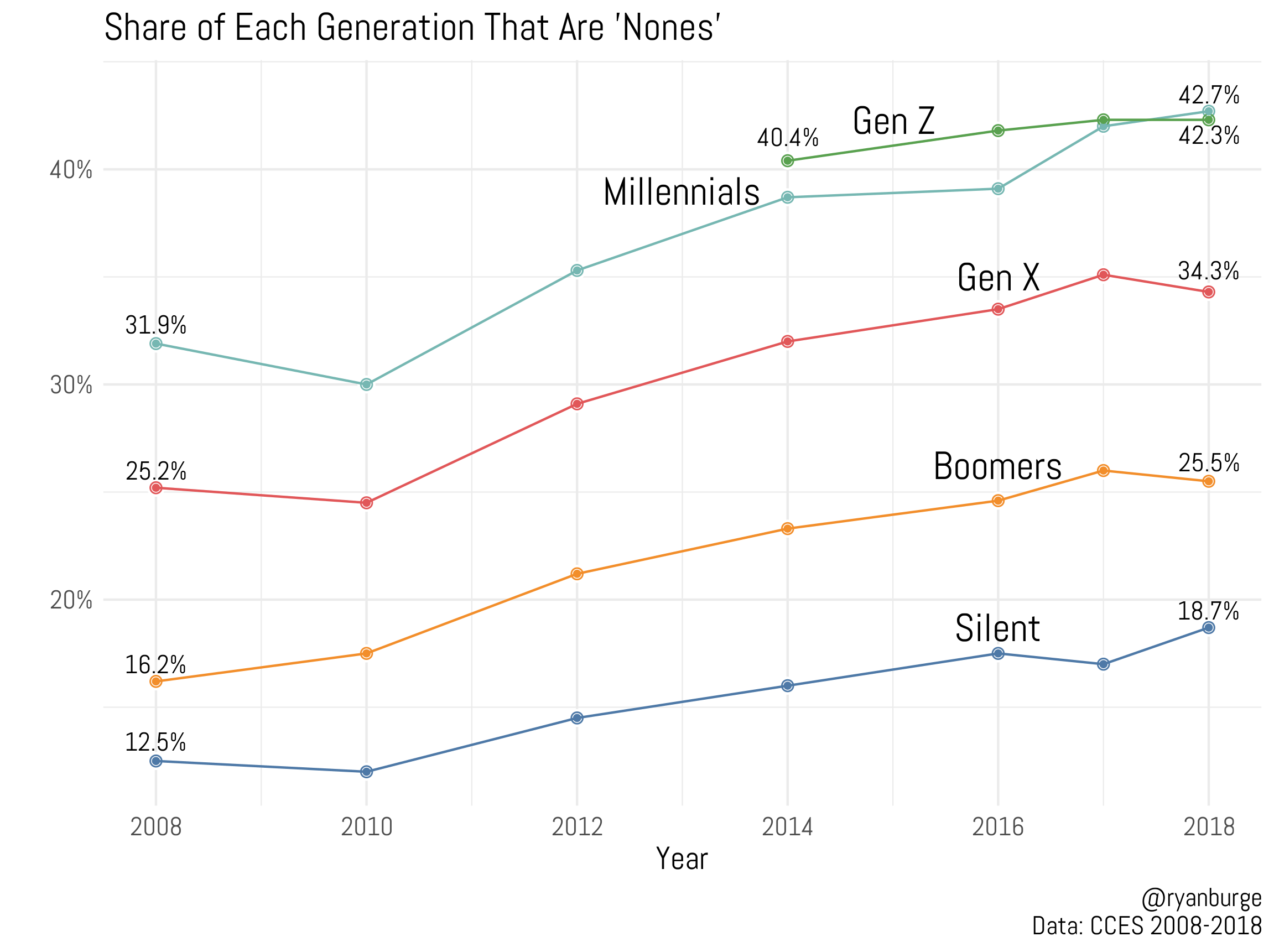

In 2008, boomers had 4 percent more nones than the Silent Generation, while Generation X was 9 percent higher than boomers. Millennials topped the charts at nearly a third of the population falling into the nones category.

That separation has persisted over the past decade. The rate of nones among the Silent Generation—the oldest subset—has increased by half, from 12.5 percent to 18.7 percent. By 2018, a quarter of boomers and a third of Gen Xers were unaffiliated. But the jump among millennials was truly unprecedented, climbing more than 10 percentage points in just 10 years to 42.7 percent.

Generation Z, during half the studied time, has appeared to chart a much different course. The rate of disaffiliation among Gen Z was just one percentage point higher than millennials in 2014. It moved up less than 2 percentage points in four years, meaning that the percentage of nones among Gen Z ended up no different than millennials: both around 42.5 percent.

Because Generation Z is still fairly young in these samples, it is possible many are still influenced by the religion of their parents. As a result, their disaffiliation may rise as they move into their late 20s and early 30s. Another possibility is that the nones have reached a natural ceiling at around 40 percent. However, that theory cannot be thoroughly tested until we have another decade of data.

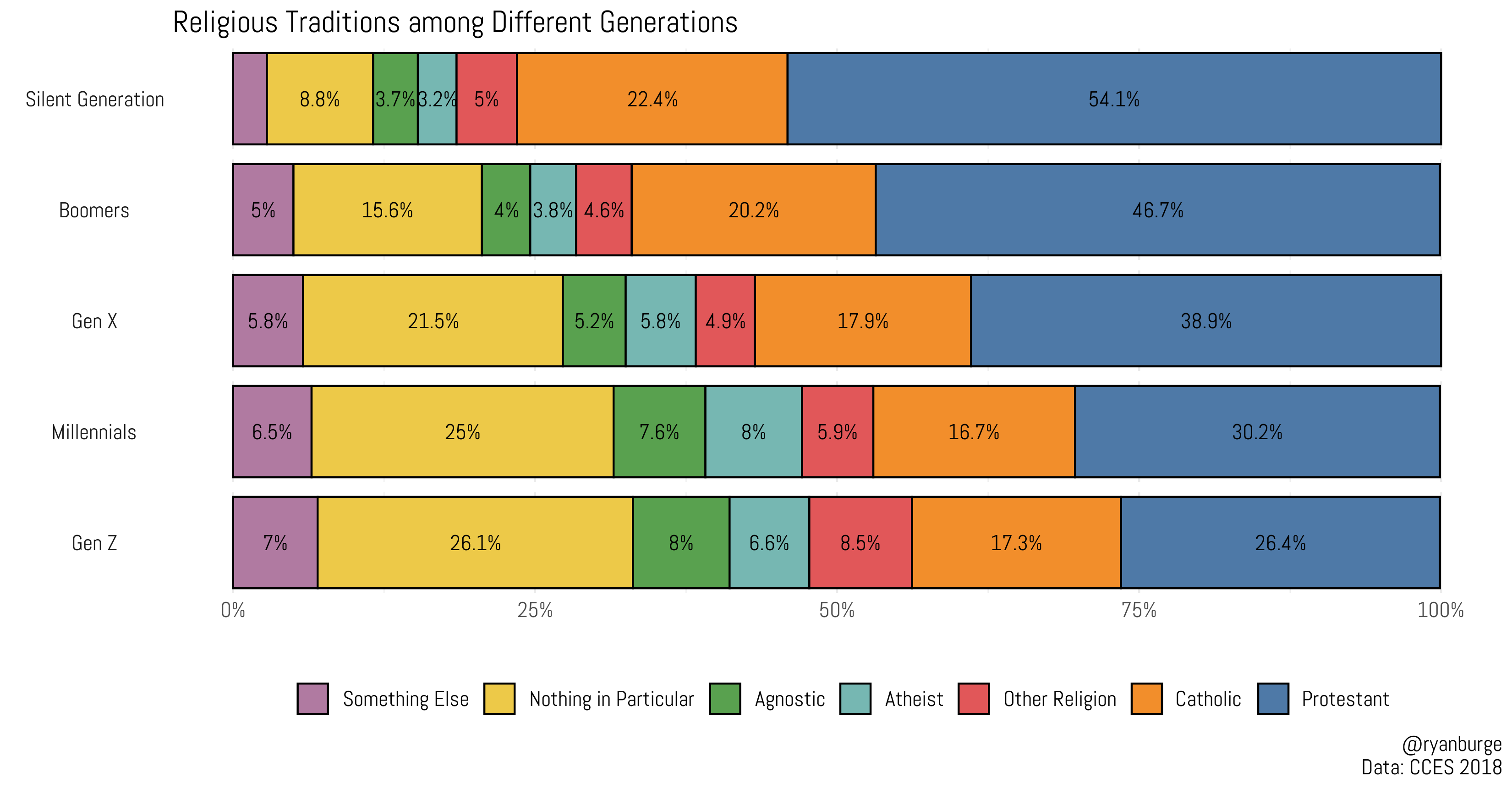

This finding does provide a glimmer of hope that religion’s decline may be abating, but there are other reasons to be cautious. Among millennials and Gen Z, though two in five are religiously unaffiliated, 60 percent are still attached to a religious tradition. This is where some different patterns emerge between the two youngest generations.

While 30.2 percent of millennials are Protestant, just 26.4 percent are in Gen Z. Today’s youngest adults are half as likely as the oldest (those born between 1925 and 1945) to belong to a Protestant church.

At the same time, the Catholic share of Gen Z has dropped by 5 percentage points, while those of another religious tradition (who responded with Buddhist, Hindu, Muslim, or Mormon) is higher, as well as the share that says that their religion is “something else.” So although the increasingly diverse Generation Z might not be growing in their disaffiliation, they are also much less likely to be Christians.

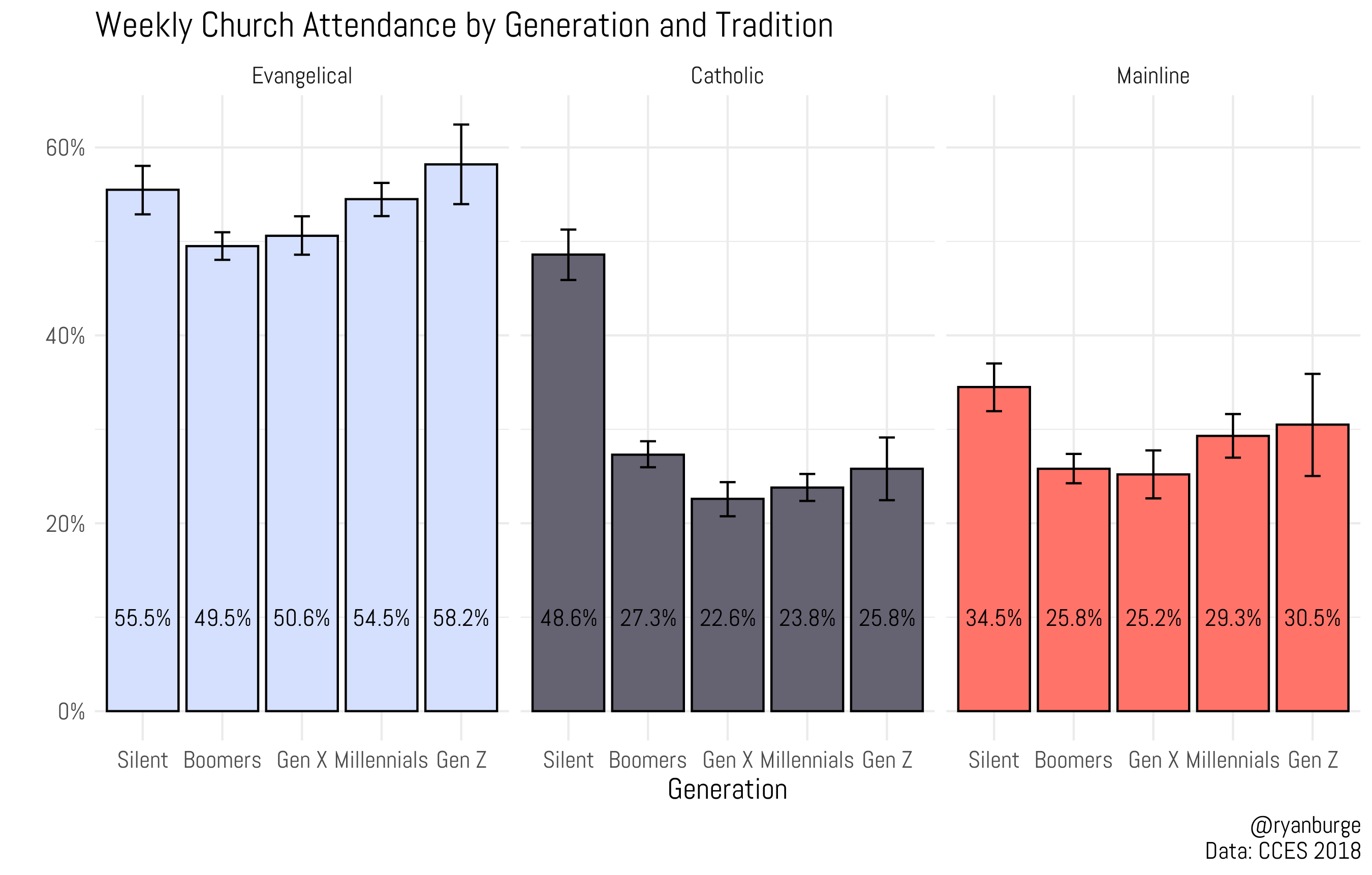

However, there is some nuance to the story regarding the religiosity of Gen Z. While the share of Gen Z that identifies as Christian is the smallest of any generation, those who still identify as Protestant or Catholic are incredibly devout. For instance, nearly 6 in 10 evangelical members of Gen Z attend church at least once a week. That’s as high as evangelicals older than 75 and statistically higher than baby boomers and those in Generation X. The same pattern emerges among mainline Protestants and Catholics, as well.

For mainline Protestants, there is no difference in weekly attendance rates between Gen Z and any other generation. For Catholics, the only cohort that attends Mass more than Gen Z is the Silent Generation, those born before 1946. The conclusion is straightforward: Though the share of Gen Z Christians is small, they are deeply committed to their faith.

It’s important to note that these data do not indicate that the overall rate of religious disaffiliation will decrease any time soon. Generational replacement is inevitable. Consider the fact that the Silent Generation, which is 18 percent nones, is decreasing by hundreds of members a day and is being replaced by Gen Z, which is 42 percent religiously unaffiliated.

There is no doubt that the rate will continue to rise, but it may find a plateau in the next few decades. At the same time, the United States will have a much smaller number of Christians, but those who remain will be committed to their faith and attend church regularly.

At the same time, the population of Buddhists, Muslims, Hindus, and those in other non-Christian traditions will become larger and more geographically dispersed across the US. Yet, even with these radical shifts in religious demography, there will still be tens of millions of Americans wrestling with issues of meaning and purpose. The mission field in the United States might be changing, but it is certainly not vanishing.

Ryan P. Burge is an instructor of political science at Eastern Illinois University. His research appears on the site Religion in Public, and he tweets at @ryanburge.