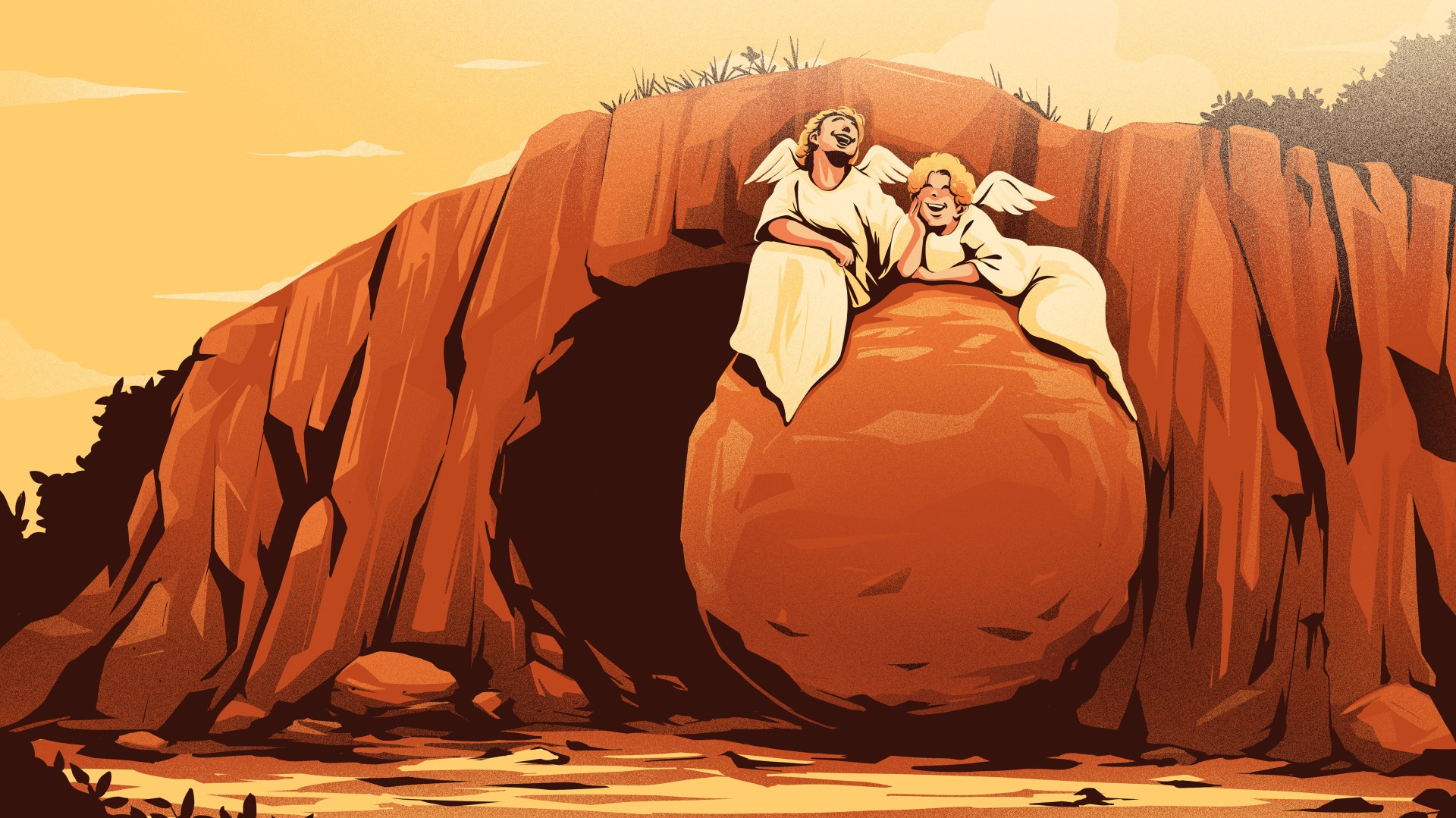

Stumbling to Jesus’ grave that first Easter morning only to find an empty tomb must have seemed like a joke. Grieving women, courageous enough to show up at the gravesite, were met by dazzling angels who delivered a riddle: “Why do you look for the living among the dead?” And then the punch line: “He is not here; he has risen!” (Luke 24:5–6). But the mourners didn’t get it. Luke’s gospel reports first bewilderment, then terror. When the grieving women dashed off to tell the disciples what they’d seen, the disciples laughed them right out of the room. We read, “They did not believe the women, because their words seemed to them like nonsense” (v. 11).

We’re told the first stage of grief is denial. “Everything happens for a reason,” people say, trying to make sense of our loss. “God needed another angel,” they’ll say, in an effort to comfort. As someone who’s suffered great loss, I know such phrases ring hollow. “Angels” and “reasons” come off as insensitive. Then again, when you turn to Luke’s Easter story, you end up with both.

Luke presents two angels and a good reason: “Remember how [Jesus] told you, while he was still with you in Galilee: ‘The Son of Man must be delivered over to the hands of sinners, be crucified and on the third day be raised again’” (vv. 6–7). The women remembered, but not the disciples. Maybe they didn’t want to remember. Rising from the dead was no laughing matter. Getting killed on a cross was the cruelest of jokes. That Jesus was forced to carry his own cross and hang on it was public shame and condemnation of the worst kind in his culture. And yet when designing our worship spaces, we Christians almost always affix big crosses to the walls. What’s wrong with us?

I once served Communion to residents of a retirement home on a Maundy Thursday afternoon. Greeting residents afterward, I asked one, her oxygen tank in tow, “How’s it going?” as if I couldn’t tell. She replied with a wink, “I’d normally say, ‘Hanging in there,’ but with this being Holy Week…” She died before the next Easter, secure in the hope that was hers in Christ.

To suffer and die—whether at the end of a long life or too terribly soon—is the one way we will all be like Jesus without even trying. Paul goes so far as to say we’ve been crucified already, that as far as God goes we’re as good as dead now (Gal. 2:19–20). Paul goes on to insist we’re raised now too—buried in baptism and raised by faith (Col. 2:12). For Christians, our future is so certain it’s like we’ve died and gone to heaven already.

Try as we might to disengage from suffering, the Cross does not let us off the hook. We may be already raised, but we still have to die.

For some, this means skipping over Good Friday to declare Easter victory. We can have our best lives right now, some preachers preach. But try as we might to disengage from hardship and suffering, the Cross does not let us off the hook. We may be already raised, but we still have to die.

We often speak of “God with us” at Christmas. “God with us” as a precious child in a manger is preferable to “God with us” as a despised man hung to die. But the manger is not the central symbol of our faith. The empty tomb isn’t either. Christians decided early on that the sign of their faith would be a cross.

Ask people to share what shaped their souls most intensely and meaningfully, and they’ll tell you stories of suffering. We understand that we’re all terminal and needy and selfish and hurtful and hurting and can’t really fix or be fixed in any permanent way in this life. But none of us really want to be fixed as much as we want to cherish and be cherished and fed and embraced and forgiven and heard and included and seen as beautiful and assured that we matter.

Page past the empty tomb, and a Christ risen again in the flesh shows himself to his disciples. Somehow they still weren’t so sure. Jesus showed them his hands and insisted they poke a finger in the wounds (John 20:27). Risen again in victory, Jesus still bore his telltale scars. He refused to hide the evidence of his hurt. We hang on to our crosses, even at Easter, because it is in the hard places of life where Christ’s presence with us proves most holy.

Scripture assures we all shall be raised, hallelujah. Just not yet, hallelujah. Life’s short enough and I’m not quite ready to go. But when my time comes, I pray for grace enough to step into that glory. “For the trumpet will sound, the dead will be raised imperishable, and we will be changed” (1 Cor. 15:52).

I’ve spent a lot of hours and Easters attempting to make the Cross and Resurrection make sense. But nothing ruins a joke like trying to explain it. So let’s leave it with this: In Christ, God is dying to love us forever. Get it?

Daniel Harrell is Christianity Today’s editor in chief.