The custom of circumcising the flesh … was given to you [Jews] as a distinguishing mark…. The purpose of this was that you and only you might suffer the afflictions that are now justly yours; that only your land be desolated, and your cities ruined by fire, that the fruits of your land be eaten by strangers before your very eyes.

—Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho, A.D. 138–161

We tend to think the birth of Christ was intended to be a blessing for the whole world. No question it eventually was seen as such, and rightly so. “Peace on earth and goodwill to men,” after all. But when the wise men came from the East, they were not looking for the universal savior, but only for the “king of the Jews” (Matt. 2:2).

When the priests and teachers explained to Herod that the Messiah would be born in Bethlehem, they quoted this verse: “And you, O Bethlehem in the land of Judah … a ruler will come from you who will be the shepherd for my people Israel” (Matt. 2:6, NLT). Not the shepherd of all people. But “for my people Israel.”

The first indication of this was noted by the angel who appeared in a dream to Joseph. After announcing that his betrothed will conceive by the Holy Spirit, the angel says, “And you are to give him the name Jesus, because he will save his people from their sins” (Matt. 1:21). Not all people. His people. That is, the Jews.

We might expect all that in Matthew’s gospel, which seems to have been written with a Jewish readership in mind. But not in the Gospel of Luke, who is said to have Gentiles in focus when he wrote his work. Yet we read in Luke 1:16 about an angel announcing to Zechariah the coming birth of John, who “will go on before the Lord,” bringing back “many of the people of Israel to the Lord their God.”

When Gabriel tells Mary that she will conceive and give birth to a son, he adds, “The Lord God will give him the throne of his father David, and he will reign over Jacob’s descendants forever” (Luke 1:32–33).

Later, when Mary and Elizabeth joyfully greet one another, Mary sings praises to God because “He has helped his servant Israel, remembering to be merciful to Abraham and his descendants forever, just as he promised our ancestors” (vv. 54–55).

When Zechariah’s tongue is finally loosed, he exclaims, “Praise be to the Lord, the God of Israel, because he has come to his people and redeemed them…” (v. 68).

There is little indication in the birth narratives that Jesus has come for the sake of the world. Instead he’s come for the most part as the new David, the Messiah of Israel, to redeem not the world or any other people, but only Israel. The arc of the gospel story from beginning almost to the end is this: Jesus came to save his people. Fast forward to the end of Luke’s Gospel to the scene with the two disciples on the road to Emmaus. When asked by a stranger what they are talking about, they reply, “About Jesus of Nazareth … We had hoped that he was the one who was going to redeem Israel” (24:20–21).

In short, while Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection have repercussions for the whole world, first and foremost, Jesus became “flesh and dwelt among us, full of grace and truth,” for the sake of the Jews.

The question is: Why did we forget this so quickly–to some extent within about a century (note the Justin Martyr quote above), and certainly within three?

Now then, let me strip down for the fight against the Jews themselves, so that the victory may be more glorious—so that you will learn that they are abominable and lawless and murderous and enemies of God. For there is no evidence of wickedness I can proclaim that is equal to this.

—John Chrysostom, from one of eight anti-Jewish sermons given in A.D. 386–387

By this time, the Jews do not seem to be a people deeply loved by God.

One reason we forgot Jesus came for the Jews is that after his conversation with the two disciples on the road, Jesus used the Scriptures to explain himself and universalize his meaning: “The Messiah will suffer and rise from the dead on the third day, and repentance for the forgiveness of sins will be preached in his name to all nations” (Luke 24:46–47, emphasis added).

We’ve read about that alongside the Great Commission in Matthew 28, alongside Paul’s adventures in preaching this message around the Mediterranean, and, soon enough, we’re thinking a lot about all nations and not much about the people of Israel. This led to the greatest movement in world history: the spreading of the Christian faith to every nook and cranny of the world. It’s a glorious story, not to be gainsaid.

But along the way, we made a mistake of monumental proportions. We forgot something crucial.

[I swear] to go on this journey only after avenging the blood of the crucified one (Jesus) by shedding Jewish blood and completely eradicating any trace of those bearing the name ‘Jew,’ thus assuaging his own burning wrath.

—Godfrey of Bouillon, Frankish knight of the First Crusade, A.D. 1095–1099

It is uncomfortable to say today that Jesus was killed by the Jews. And for good reason: That has led to the most vile and ugly racism the world has ever known. Theologically, it is crucial to say that we killed Jesus. All of us, Jew and Gentile. Legally and in fact, it was the Romans who literally killed Jesus. But for the sake of this article, let’s take note of this as well: Jesus was killed at the instigation of the Jews, who chanted, “Crucify him! Crucify him!” forcing the hand of a weak-willed Pilate. And here is the marvelous thing, contra Godfrey of Bouillon: He forgave them as he was dying. He did not reject, let alone forget, his people. He not only forgave them, but he told his disciples that his gospel should be preached “beginning in Jerusalem.” Even though his message is universalized, Israel still comes first.

Paul is absolutely clear on this point. He never forgets Israel’s priority place in the heart of God. The gospel is the power of salvation “to everyone who believes,” but “first to the Jew…” (Rom. 1:16).

Paul was never in danger of forgetting this. The fact that most Jews failed to recognize Jesus as Messiah tears him apart. “My heart is filled with bitter sorrow and unending grief for my people, my Jewish brothers and sisters. … They are the people of Israel, chosen to be God’s adopted children. God revealed his glory to them. He made covenants with them and gave them his law” (Rom. 9:1–4, NLT).

Perhaps the linchpin of his understanding comes next: “Christ himself was an Israelite as far as his human nature is concerned. And he is God, the one who rules over everything and is worthy of eternal praise!”

That’s a marked contrast to Justin Martyr and John Chrysostom, who seem to glory in Jewish suffering, which they chalk up to Jewish rejection of Jesus. They gloat. Paul weeps.

It’s even more of a contrast with Godfrey of Bullion and Martin Luther, who seek revenge.

What shall we Christians do with this rejected and condemned people, the Jews? Since they live among us, we dare not tolerate their conduct, now that we are aware of their lying and reviling and blaspheming…. I shall give you my sincere advice:

First to set fire to their synagogues or schools and to bury and cover with dirt whatever will not burn, so that no man will ever again see a stone or cinder of them. This is to be done in honor of our Lord and of Christendom, so that God might see that we are Christians…. Second, I advise that their houses also be razed and destroyed. … Third, I advise that all their prayer books and Talmudic writings, in which such idolatry, lies, cursing and blasphemy are taught, be taken from them…. Fourth, I advise that their rabbis be forbidden to teach henceforth on pain of loss of life and limb.

—Martin Luther, “The Jews and Their Lies,” A.D. 1543

We rightly stand in awe at the mystery that God become flesh and dwelt among us. We glory in the specificity of his life—sucking on the breast of Mary, learning carpentry from Joseph, living a daily and dusty life in the lost corner of the world called Nazareth, and so on. We often fail to appreciate that God took on Jewish flesh; that God, when he decided to become a man and walk among us, decided to do it as a Jew.

If we celebrate the Incarnation because it esteems the value of our material bodies, we should also celebrate it because it manifests the glory of the Jews, with whom, out of all the peoples on the earth, God decided to dwell. Jesus died on the cross as a Jew—“the King of the Jews” was written on a plaque on the cross in three languages. When Jesus rose bodily from the dead, his body was that of a Jew. And as Jesus now sits at the right hand of the Father, he does so as a Jew, the Chosen One of the chosen people.

This is not a new idea. Karl Barth noted it some decades ago:

There is one thing we must emphasize especially. … The Word did not simply become any “flesh.” … It became Jewish flesh. … The Church’s whole doctrine of the incarnation and atonement becomes abstract and valueless and meaningless to the extent that [Jesus’ Jewishness] comes to be regarded as something accidental and incidental (Church Dogmatics 4/1).

If God has invested so much in these Jews and in this one Jew—well, a most blessed and glorious people they must be.

Now the measures of the state towards Judaism in addition stand in a quite special context for the church. The Church of Christ has never lost sight of the thought that the “chosen people,” who nailed the Redeemer of the world to the cross, must bear the curse for its action through a long history of suffering… . But the history of the suffering of this people, loved and punished by God, stands under the sign of the final homecoming of the people of Israel to its God. And this home-coming happens in the conversion of Israel to Christ….This conversion, that is to be the end of the people’s period of suffering.

—Dietrich Bonhoeffer, “The Church and the Jewish Question,” 1933

Paul goes on in Romans, yes, to expand the notion of “the chosen people” so that it includes everyone who is not Jewish. But never does he suggest that, because the Jewish people as a whole have rejected Jesus, God now rejects them, or worse, causes their suffering, as Bonhoeffer and nearly every Christian before him believed. No, just the opposite: “God has not rejected his own people, whom he chose from the very beginning” (Rom. 11:2, NLT).

Yes, they have “stumbled,” but not so far as to “fall beyond recovery” (Rom. 11:11). In fact, God is using their transgression as a means to bring salvation to Gentiles—“their rejection brought reconciliation to the world” (v. 15). If that’s what their rejection means, “what will their acceptance mean but life from the dead?” Paul doesn’t say “if” they accept, but he speaks about their acceptance as if it will happen at some point.

And then he makes absolutely clear the relationship of Jews to Gentiles: Gentiles are like branches grafted on to the roots and the trunk of the tree (Rom. 11:17–18). The main thing is Israel. Israel is the privileged people. The Gentiles are—to not put too fine a point on it—second-class citizens. There is a hierarchy in the scope of salvation, and the Jews are at the top.

It’s as if Paul is saying, “And Gentiles, don’t you forget it.”

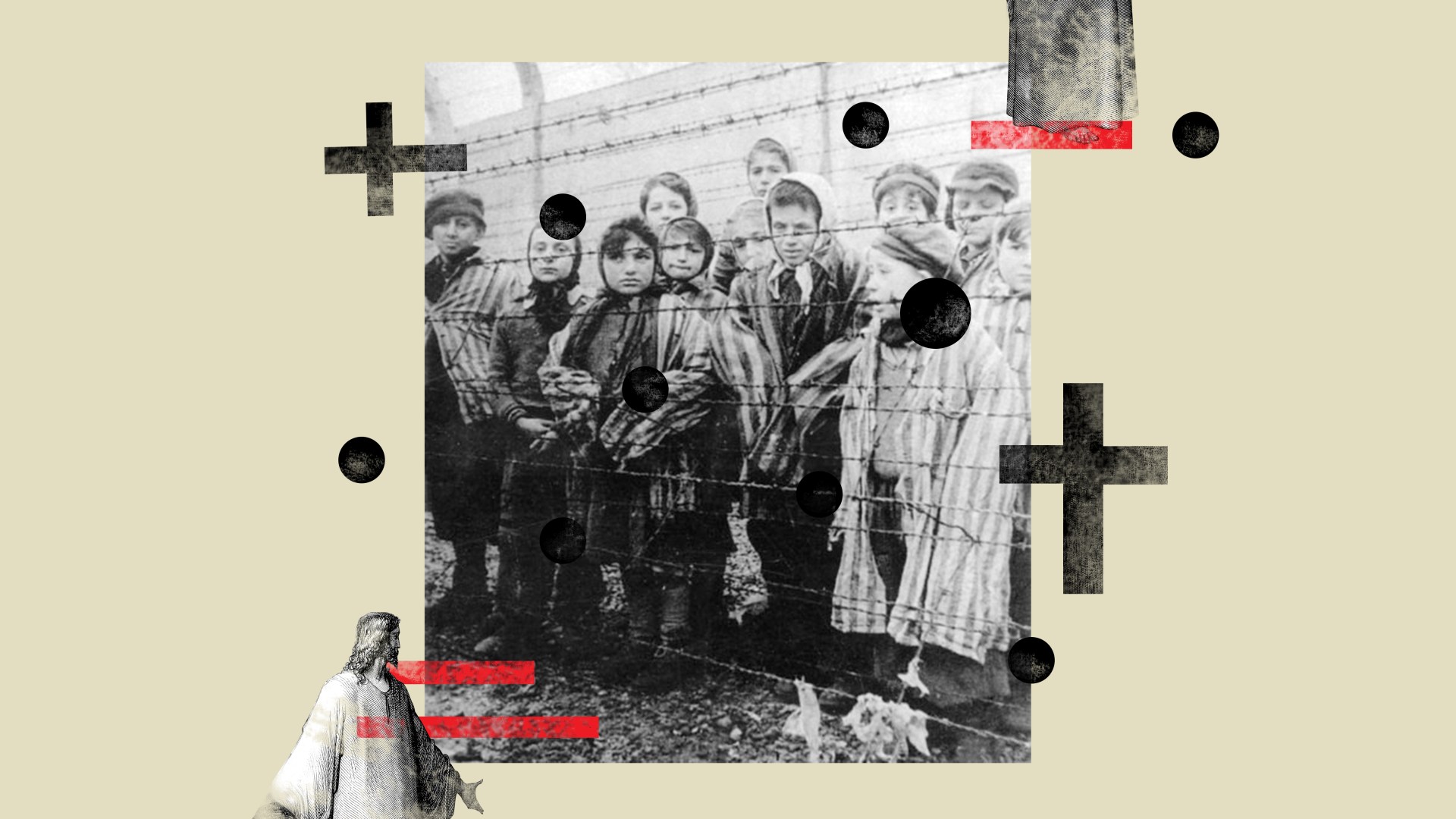

But we did forget it. And because we forgot it, the world, especially the Christian world, took note and decided that the Jews should become merely a memory.

We were packed into a closed cattle train. Inside the freight cars it was so dense that it was impossible to move. There was not enough air, many people fainted, others become hysterical…. In an isolated place, the train stopped. Soldiers entered the car and robbed us and even cut off fingers with rings. They claimed that we didn’t need them anymore. These soldiers, who wore German uniforms, spoke Ukrainian. We were disoriented by the long voyage, we thought we were in Ukraine. Days and nights passed. The air inside the car was poisoned by the smell of bodies and excrement. Nobody thought about food, only about water and air. Finally we arrived at Sobibor.

—Ada Lichtman, who was deported to Sobibor and was selected to be one of the few Jews working in the concentration camp and later escaped, 1942.

We not only forgot it, our minds moved in the exact opposite direction. Deriding the Jews. Spitting on Jews. Harassing Jews. Killing Jews. And we taught, by word and example, one of the most cultured Christian nations, thoroughly imbued with Lutheran sensibilities, to do the same. If by your fruits you shall know them—well, what does that say about us? When it comes to the Jews, what does our fruit taste like?

In the morning or noon time we were informed by Wirth, Schwarz, or by Oberhauser that a transport with Jews should arrive soon. … After the disembarkation, the Jews were told that they had come here for transfer and they should go to bath and disinfection.

… My post in the “tube” was close to the undressing barrack. Wirth briefed me that while I was there I should influence the Jews to behave calmly. After leaving the undressing barracks, I had to show the Jews the way to the gas chambers.

I believe that when I showed the Jews the way, they were convinced they were really going to the baths. After the Jews entered the gas chambers, the doors were closed by Hackenholt himself or by the Ukrainian subordinate to him. Then Hackenholt switched on the engine which supplied the gas. After five or seven minutes—and this is only an estimate—someone looked through the small window into the gas chamber to verify whether all inside were dead.

Only then were the outside doors opened and the gas chambers ventilated. After the ventilation of the gas chambers, a Jewish working group under the command of their kapo’s entered and removed the bodies from the chambers….

The corpses were besmirched with mud and urine or with spit. I could see that the lips and tips of the noses were a bluish color. Some of them had their eyes closed, others eyes rolled. The bodies were dragged out of the gas chambers and inspected by a dentist, who removed finger-rings and gold teeth. After this procedure, the corpses were thrown into a big pit.

—Karl Alfred Schluch, describing his experience at the Belzec Concentration Camp, 1942

The Jews to us have not been the apple of God’s eye but a people under a divine curse. They were not beloved for the sake of their ancestor Abraham, but were seen only as Christ-killers. And so we became Jew-killers.

Report No. 51 of Reichsfhrer-SS Heinrich Himmler to Hitler about mass executions in the east, 1942.

| – |

August |

September |

October |

November |

|

Prisoners executed after interrogation |

2,100 |

1,400 |

1,596 |

2,731 |

|

Accomplices of guerrilla and guerrilla suspects executed |

1,198 |

3,020 |

6,333 |

3,706 |

|

Jews executed |

31,246 |

165,282 |

95,735 |

70,948 |

|

Villages and localities burned down or destroyed |

35 |

12 |

20 |

92 |

To put it another way, over the centuries, the Jews became the mirror image of Jesus: “He was despised and rejected—a man of sorrows, acquainted with the deepest grief. We turned our backs on him and looked the other way. He was despised, and we did not care” (Isa. 53:3, NLT).

Can we not see that in rejecting the Jews, we have in some sense rejected our Lord?

For I was hungry and you gave me nothing to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me nothing to drink, I was a stranger and you did not invite me in, I needed clothes and you did not clothe me, I was sick and in prison and you did not look after me (Matt. 25:42–43).

Perhaps it is the Jews—who were ethnically, culturally, religiously his brothers and sisters—whom Jesus also had in mind when he told this parable. If that is the case, woe to us Christians who have not merely forgotten these least among us but have put them in prison and taken away their clothes and let them starve. And if that was not enough, we set such an example of hate that nation after nation steeped in Christian faith—Germany, France, Poland, and on it goes—thought nothing of harassing and killing the least of these.

Yes, there has always been a small minority of noble and brave Christians who have stood up for the least of these. Some of them commoners, some kings and popes. But always a small minority.

I hear, “Oh, but they weren’t evangelical Christians, they were not real Christians. If we had been the major expression of Christianity, we would have never done something so horrible.” Except when we were the main expression of American Christianity, we enslaved Africans by the millions, treating them with a cruelty that can only be compared to the Holocaust. No, all have sinned and fall short of the glory of the God of the Jews.

But why? Why have we spent two millennia participating in such cruelty? What was that all about? How could we be so obtuse? Not to put too fine a point on it—how could we be so evil?

The rulers of the Third Reich wanted to crush the entire Jewish people, to cancel it from the register of the peoples of the earth. Thus the words of the Psalm: “We are being killed, accounted as sheep for the slaughter” were fulfilled in a terrifying way. Deep down, those vicious criminals, by wiping out this people, wanted to kill the God who called Abraham, who spoke on Sinai and laid down principles to serve as a guide for mankind, principles that are eternally valid. If this people, by its very existence, was a witness to the God who spoke to humanity and took us to himself, then that God finally had to die and power had to belong to man alone.”

—Pope Benedict XVI, speaking at Auschwitz, 2006

Let’s not try to weasel out of this by saying, no, we were not members, let alone rulers, of the Third Reich. Let us not pretend that there is no evidence that Christians have, certainly at times, wished “to cancel [the Jewish people] from the register of the peoples of the earth.” History shows that Christians were only too willing to go along with the Third Reich, sometimes egging it on, sometimes guiltily looking the other way.

This sounds horrid, and it is. Then again, our participation in this sin against the Jews is as old as history, and is the same as that of Adam and Eve—the yearning to be free from God that we might be like gods. Our sin against the Jews is the same as the hard-heartedness with which all of us put Jesus on the cross. At base, we do not want to be ruled by God.

The Roman Catholic and Anglican churches teach that at the Eucharist, Christ’s death on the cross is re-presented. He is not sacrificed again, but his death is presented to our eyes and bodies and souls afresh. One does not have to buy into the doctrine of transubstantiation or even real presence to see the value of thinking about the Lord’s Supper in this way.

But this re-presenting has not just happened at each and every Eucharist, but also at each and every pogrom, at each and every slanderous word spoken against the chosen people, at each and every man, woman, and child who suffocated in jammed box cars or who inhaled deadly gas in a barren and cold “shower room.” As we have sinned against the least of these, we have re-presented Christ on the cross, and the chosen people were re-presented, collapsed into the body of the Chosen One, pressed with divine force into him, in a fusion of judgment and mercy, of sinner and redeemed, of this age and the next.

And what he prayed on the cross he has prayed ever since, year after year, century after century, pogrom after pogrom, train car after train car, crematory after crematory: “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.”

My Jewish readers are surely not happy at this point—if after five years of interfaith dialogue I understand them. If there was ever a statement that seems like cheap grace, this is it—that Jesus forgives the most heinous sins in history. Just like that. With a mere breath of words.

To many of my Jewish friends, forgiveness for such a sin would be immoral. (I’m thinking especially of the powerful essay by Meir Y. Soleveichik, “The Virtue of Hate.”) And even if this impossibility were to become possible somehow, many Jews would demand that forgiveness must be preceded by a desperate repentance and heroic effort at atonement.

For the Christian, it works in just the opposite fashion.

First comes the forgiveness.

Then comes the atonement.

Then comes the repentance.

Jesus forgives our sin while on the cross, and then dies to atone for our sin. And now he calls us to repentance. I grant that this whole business is more theologically complex than this simple summary. But it’s still not a bad summary of how things work. We don’t earn our salvation, but we certainly work it out in fear and trembling.

To put it another way, Jesus’ word of forgiveness and his work of atonement do not give us a free pass. Repentance is not a one-time event but a lifelong journey. Martin Luther’s first thesis of 95 put it like this: “When our Lord and Master Jesus Christ said, ‘Repent’ (Matt 4:17), he willed the entire life of believers to be one of repentance.”

No, the Cross is not a free pass as much as it is a work permit. And the work permit in this case says this:

The bearer of these divine gifts is entitled and commanded the following: Love your Jewish brothers and sisters like you’ve never loved them before. Love them year after year, century after century, maybe for two millennia. Show them what repentance looks like. And then, maybe, when you tell them about the forgiveness of Jesus, then, maybe, they might be willing to listen. And then, maybe, they also might forgive you.

Mark Galli is editor in chief of Christianity Today.

Note: This article has been edited for clarity since its original publication.