You probably know someone who’s given their child, and especially their baby boy, an obscure biblical name. Sunday schools are increasingly filled with baby boys named Asher, Silas, Hezekiah, or Ezra. Meanwhile, boy names like John, Michael, David, and James appear to be falling out of favor.

The numbers back up this perception. According to current data from the Social Security Administration, “unusual” biblical names are getting more common for baby boys, with historically “rare” Bible names rising from about 0.5% of boys in the 1950s to a whopping 6.5% of baby boys today. Of all baby boys given uncommon or unconventional names, 17% had uncommon biblical names—the highest share since 1880.

What’s going on? Why are there so many Obadiahs and Eliases underfoot? And how do these name trends reflect religious and cultural patterns in the United States?

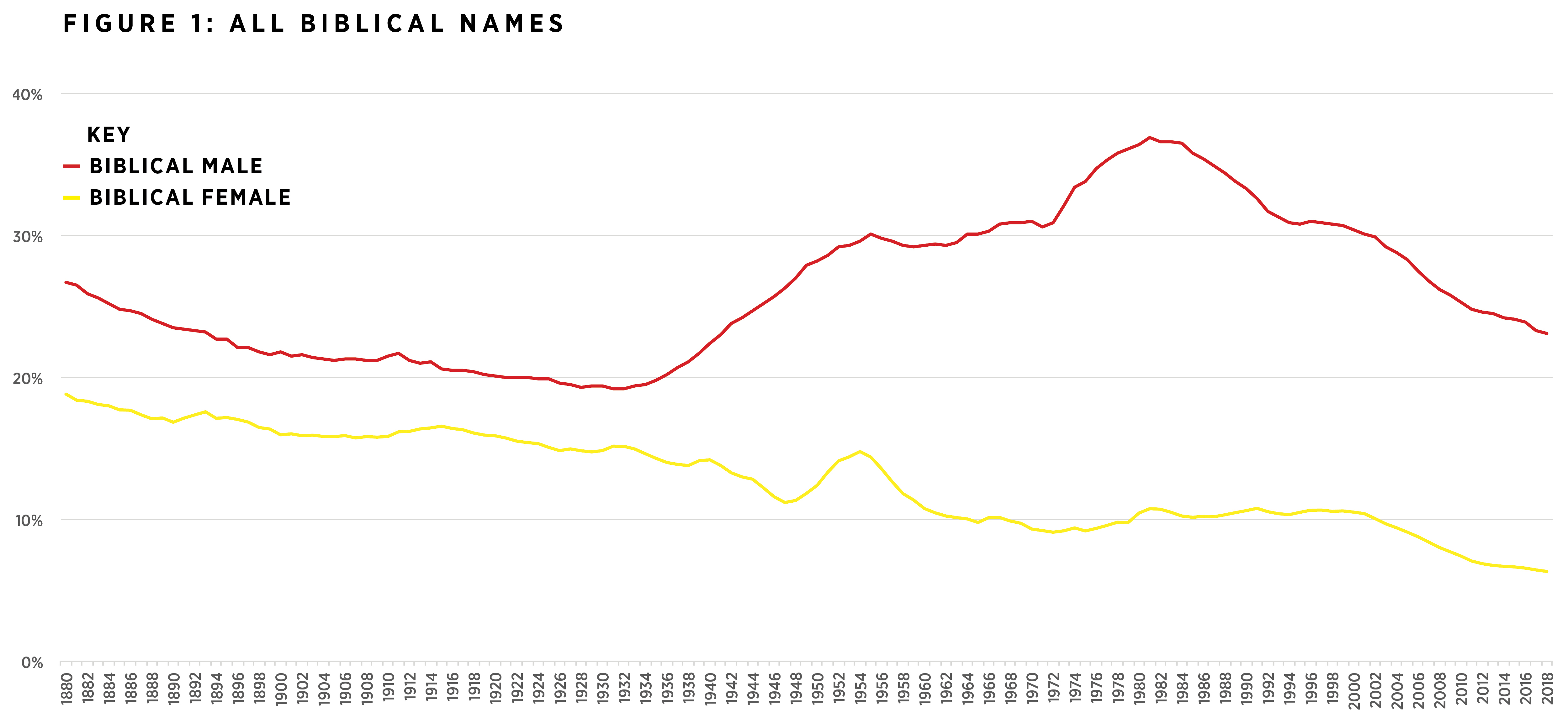

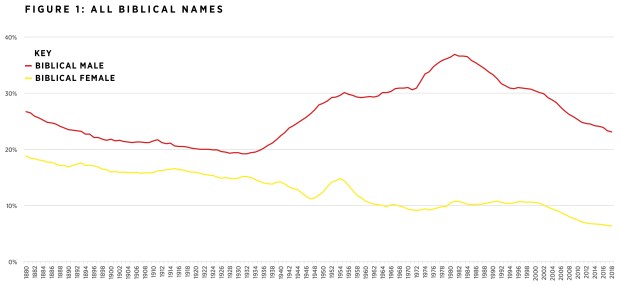

To understand the picture, we have to go back in time and look first at the numbers. Baby boys born in 1982 were more likely to have biblical names than in any other year since 1880, driven by the increased popularity of names like David, Matthew, Joshua, Daniel, and Timothy. While biblical boy names rose steadily in prominence from 20% of baby boys in 1935 to more than 35% in the early 1980s, baby girls saw a different trend. From 1880 until 2018, the share of baby girls with biblical names has fallen steadily from 19% to around 6% today.

The rise in biblical boy names from 1880 to 1980 mostly included the monikers of major characters from the Old or New Testament. In other words, parents gave their kids names that were generically spiritual: They referred to the Bible, but they weren’t too religious sounding. There were more Davids and fewer Levis, more Timothies and fewer Barnabases.

The trend in names is partly explained by corresponding religious trends. Declining anti-Semitism and anti-Catholicism broadened the number of socially acceptable names. And as US religious membership peaked between the 1950s and the 1980s, the cultural ascendancy of mainline and evangelical Protestantism meant that families increasingly wanted boy names that were recognizably biblical but still relatively conventional.

Girl names have a quite different backstory. Because girls are less likely to be named after their parents, baby girls have always had more diverse names and less standardized name spellings (like “Aleczandra,” for instance).

Baby girl monikers are also generally more susceptible to “name bubbles,” meaning that very large numbers of girls have names that were only popular during a particular period. In 1929, for example, one in every 1,750 baby girls was named Judith. By 1940, it was one in every 53. By 1950, Judith’s popularity had fallen by half, and by 1956, by half again. While some boy names show similar fads, it’s considerably less common.

In recent years, baby girls just like baby boys have seen a rise in less common biblical names. Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, and Mary are down, while Naomi, Eve, Delilah, Hannah, Eden, Leah, and Esther are up. Even names like Hadassah, Azariah, and Amariah are seeing growth, while Elizabeth and Susannah are falling into disuse. Both girls and boys with biblical names are increasingly getting very biblical names.

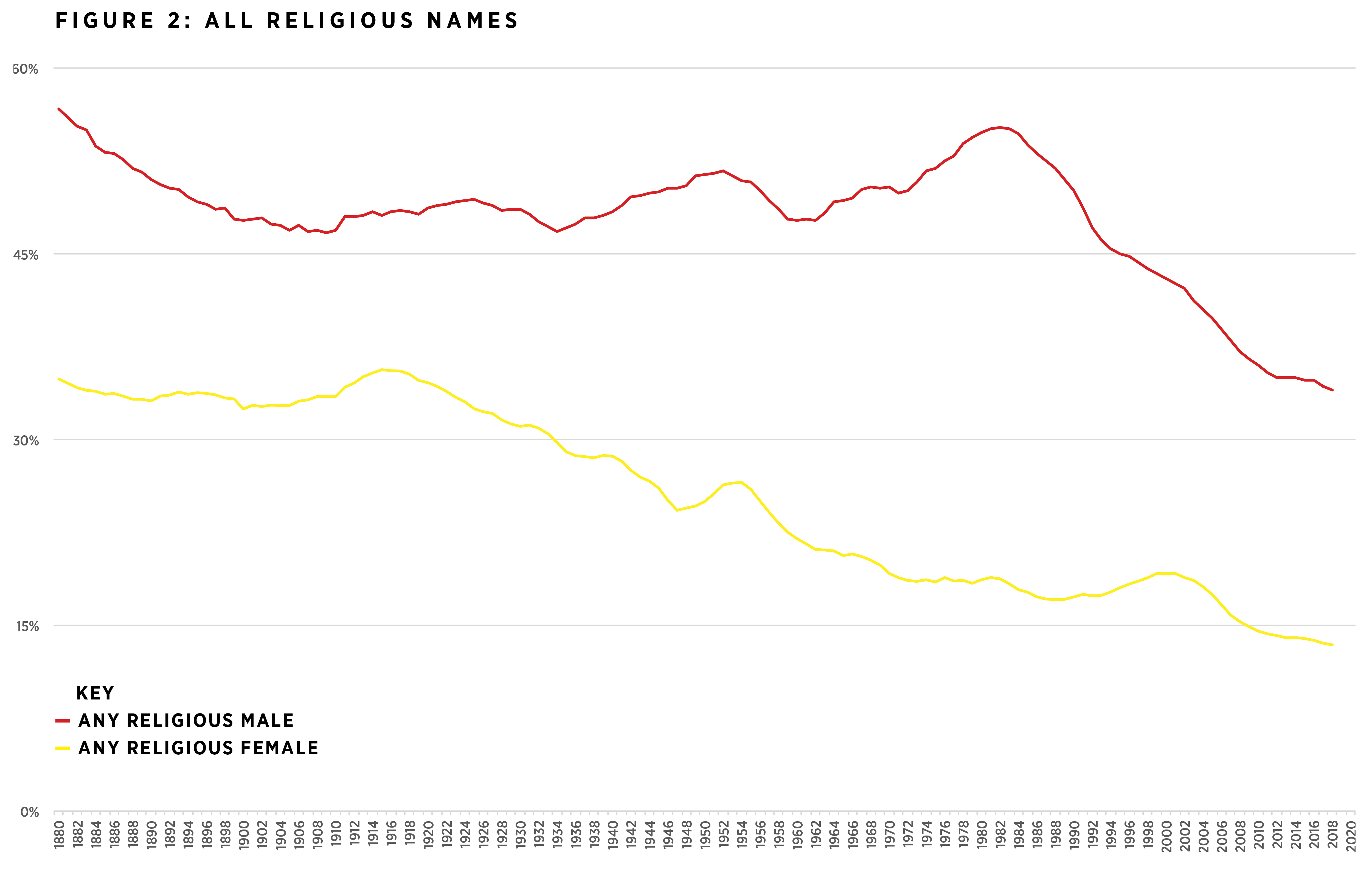

However, to sort out these trends—and what’s behind them—we have to look at more than just the strictly biblical names. Many “religious” names aren’t biblical: Girls are often given virtue names like Charity, Peace, or Hope, and some parents give their children names that are religious but not directly scriptural, like Benedict.

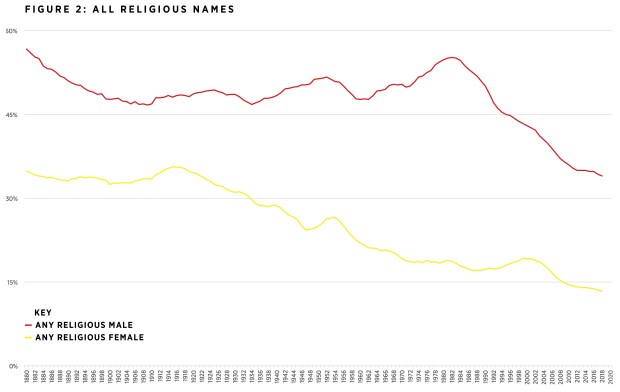

To get at these variables, I added a list of all Roman Catholic Saints, English-language virtue names, names appearing in the Qur’an, and names derived from Hindu gods. Together, they gave me an estimate of all religious names (see Figure 2).

Accounting for these religious-but-not-biblical names smooths out the historic trends. Boy names have approximately stable religious shares from 1880 to 1980, and religious girl names are stable from 1880 to about 1920. But since 1980 for boys and 1920 for girls, religious names of any kind have steadily declined as a share of names.

This pattern reflects a wider trend in American society: the diminished role of religion in peoples’ lives.

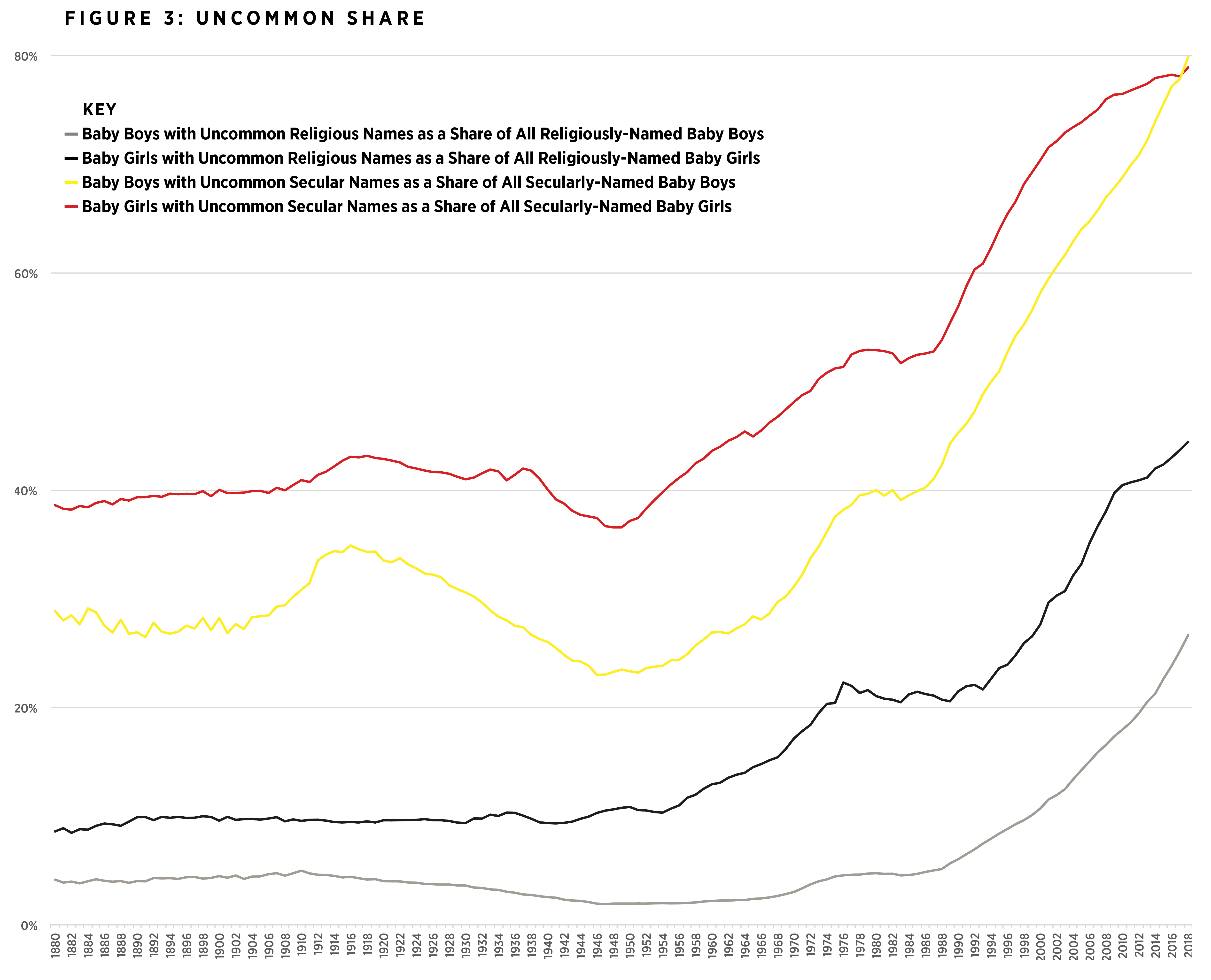

Over the last 140 years, Americans have gradually moved away from a society marked by conventionalism and conformism to one of extreme individualism. Since the 1990s, especially, we’ve been living through a significant wave of anti-conventional fervor (although the baby boom period saw a similar explosion in highly individualized names). Baby names increasingly reflect the very specific interests, values, or idiosyncracies of parents, not just family traditions or wider public norms.

This shift tracks the wide turn away from a public culture dominated by religious ideas and toward one where popular consumerism is the driving force. (That this pattern appeared earlier for girls simply reflects the greater willingness of parents to give girls trendy names.) Combined, these two changes—toward more nonconformist baby naming and less religious baby naming—speak to a truly seismic cultural shift. Americans today are less governed by religious ideas, yes, but they’re also less governed by any particular convention.

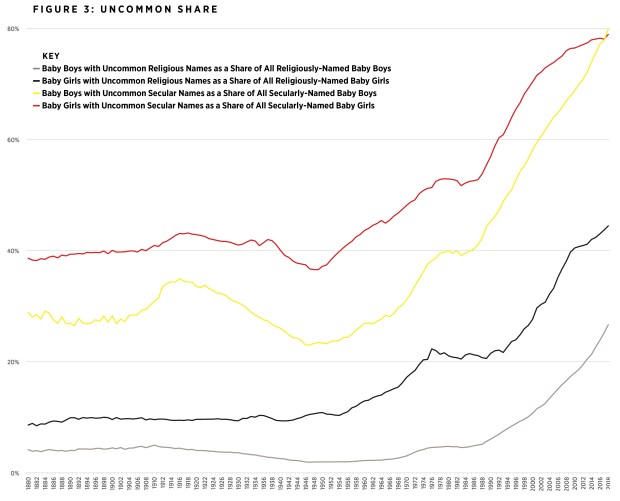

The figure below illustrates these growing nonconformist sensibilities by showing the share of baby boys and girls with religious or secular names that are notably uncommon.

The recent rise in quirky biblical names seems to fit into this larger picture of nonconformism. While kids with nonreligious names are much more likely to have uncommon names, the overall rise in unconventional names has been similar in size and timing across all four groups shown in the graph above. Religious parents are adapting to this new individualist world, giving their kids names that maintain the public claim of faith while also responding to a wider cultural demand for uniqueness and originality.

In other words, parents of faith want their kids to stand out from the crowd just as much as secular parents do.

Looking forward, there’s plenty more space for creativity with highly unique but still highly religious names. Of the 2,606 biblical names I track in my ongoing research, only 811 ever had a year with more than 4 baby boys or girls given that name. We haven’t yet seen kids named Abijam or Paltiel, nor have we seen name fads for Philetus or Berechiah. Even notably faithful biblical figures like Ehud, Elkanah, Habakkuk, Hilkiah, and Jehonadab have been passed over.

So if you thought your Sunday school attendance list included some really deep cuts into the Bible, you weren’t wrong. Because unusual religious names were extremely rare before the 1970s, names like Hezekiah or Jael, Enoch or Salome are easy to spot. You weren’t imagining things: Religious names are getting strange!

This, I think, is actually cause for optimism. Even amidst a sea of cultural individualism that knows no law above the will, families are finding ways to translate the witness of Christian identity for the next generation. At a time when baby names seem to evince a society where parents do what is right in their own eyes, a committed religious minority is doubling down and giving their children names that cannot help but draw attention to the faith in which they were raised.

If we’re lucky, then, maybe we’ll live to see kids named Maher Shalal Hash Baz once again.

Lyman Stone is an adjunct fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, a research fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, and the chief intelligence officer of the consulting company Demographic Intelligence. He and his wife live in Hong Kong and serve as missionaries in the Lutheran Church (Hong Kong Synod).