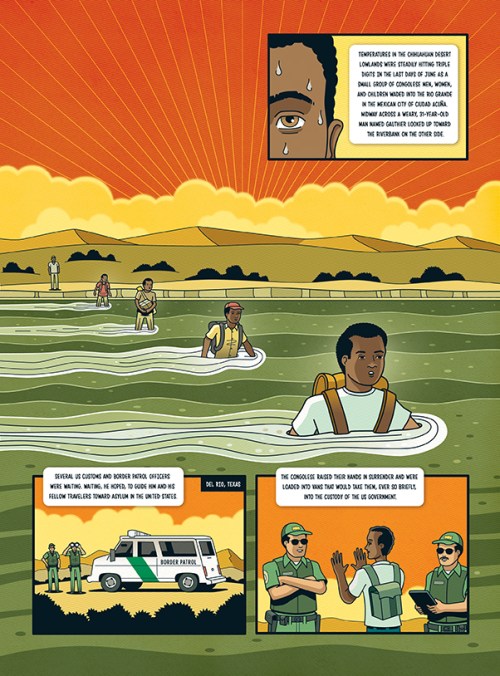

Temperatures in the Chihuahuan Desert lowlands were steadily hitting triple digits in the last days of June as a small group of Congolese men, women, and children waded into the Rio Grande in the Mexican city of Ciudad Acuña. Midway across a weary, 31-year-old man named Gauthier looked up toward the riverbank on the other side, in Del Rio, Texas. Several US Customs and Border Patrol were waiting.

Waiting, he hoped, to guide him and his fellow travelers toward asylum in the United States.

The Congolese raised their hands in surrender and were loaded into vans that would take them, ever so briefly, into the custody of the US government. After two days—a mere formality of registering their presence in the US—the hungry and exhausted travelers would undergo what they prayed was the final leg of their escape from war and violence.

They had varying destinations in mind. But most of them were bound for Portland, Maine, where they knew they would find a critical mass of French-speaking Africans.

What they didn’t know exactly was how they would get there from Texas. Or that lining the routes was an invisible network of ministries, anonymous hands waiting to deliver them food, showers, and travel assistance. Or that in one of the least-churched cities in America, a small but scrappy community of both white and Central African believers was already waiting for them.

Del Rio, Texas

The Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) sector in Del Rio is one of the agency’s sleepier offices on the Southwest border, in part because the city of Del Rio and its Mexican counterpart, Ciudad Acuña, are surrounded by hundreds of miles of desert. But by June it was already doubling and tripling its usual monthly apprehensions.

Families and minors fleeing violence in Central America were being joined by migrants from nearly 50 other countries, including more than 700 from African nations including the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Angola. Migrants requesting asylum are given appointments for interviews with immigration officers or judges, but the process of making their case and awaiting final decisions can take months, if not years.

With so many applicants to house, processing centers and detention centers were running out of room. What little remained needed to be saved for those deemed potentially dangerous.

With nowhere else to turn, the sector knew it would have to start releasing families and detainees without criminal records.

“We saw this coming, where we knew we were catching too many people,” CBP Del Rio sector assistant chief patrol officer Brady Waikel said. “The whole system was coming to a breaking point. So we started making plans.”

The problem, he explained, is that Del Rio, population 36,000, is not where most people want to be released. Compared to other communities in Texas, Del Rio doesn’t have much to offer migrants in the way of community or social services. Or rather, it didn’t, until CBP reached out to several churches in May of this year.

“We weren’t particularly looking for a faith-based group,” Waikel said. “That’s all there was here.”

A group of four churches answered the call. Shon Young, an associate pastor for outreach at City Church Del Rio, likened the process to building a plane while flying it. No sooner had the group gained access to a City of Del Rio neighborhood facility—a warren of narrow hallways now lined with donations spilling out of ersatz stock rooms and offices, and a large gym now lined with cots and space for children to play—than immigrant families were being dropped off there by CBP.

As the number of detentions surged into June, the loose coalition realized it would need to formalize its relationship and form a nonprofit. Meeting the needs of up to 100 people per day required more resources than the churches had. Supplies, from toothbrushes to cots to food, were depleted quickly.

So the four churches formed the nonprofit Val Verde Border Humanitarian Coalition, enabling them to receive more donations, among other benefits. That’s when things started to take off, Young said. “God has used people from all walks of life.”

For instance, in June, a San Antonio blogger wrote about the effort, and the post was seen by actor Misha Collins, who then tweeted a donation link to his 2.9 million followers. Boxes and boxes from the group’s Amazon wishlist began arriving in huge trucks.

In late July, Samaritan’s Purse reached out, as it did to churches and faith-based nonprofits in eight other border cities, to infuse support. With shower trucks and food prep trucks used in disaster relief, Samaritan’s Purse provided badly needed facilities until the coalition could make more permanent arrangements at the community center.

While the center only takes women and families, Young also found ways to help some of the single migrant men—connecting them with other places to rest, shower, and eat a meal before continuing on their journey. The stories of the Congolese men moved him. Their journey had been long, brutal, and difficult to imagine in today’s globally connected world of ubiquitous leisure travel.

“It actually reminded me of when Israel was in the wilderness,” Young said. “The way they were going was uncharted, and they didn’t know if the direction they were following was right or wrong. It must have stretched their faith, how they would overcome one obstacle just to be met with another. And how discouraging it must have been when they came across the people who didn’t survive.”

The center has become an invaluable part of the immigration system in Del Rio, Waikel said. “We need them,” he said. “If it wasn’t for them these people would still be being released, but they’d just be released on the street.”

Del Rio is no more than a first stop for most migrants entering there. “I have yet to hear of any of them say that this is where they want to be,” Waikel said.

Most, he explained, are in route to somewhere farther from the border. “They’re wanting to be in other places in New York, in Maine, in other locations that have their friends and family.”

A major part of the coalition’s ministry is to help the newly arrived immigrants figure out their route to their final destination. Most need help navigating the series of buses and planes they will need to take.

Portland, Maine, has become the destination of choice of French-speaking Central Africans. The city doesn’t have the largest Congolese immigrant community in America, but it has extended an explicit welcome to the most recent wave of asylum-seekers. A stable community of Congolese has gathered there over the decades as fighting between rebel groups in DRC has displaced 4.5 million people inside the country and driven 800,000 more out of its borders.

But next up on this 2,300-mile journey would be San Antonio, the closest major city, 150 miles away.

San Antonio, Texas

Waiting to embark on the journey to Maine, Gauthier sat on the sidewalk outside San Antonio’s Migrant Resource Center. He had made it this far, after a long and grueling journey from the DRC that finally led him across the Rio Grande into Del Rio and now to San Antonio.

Gauthier, who asked that his last name be withheld for his safety, does not have much to say about why he left his home in Kinshasa.

“There is much difficulty, much war,” he said in French. “It has led to much death.”

The US has long taken on refugees from the DRC. The Migration Policy Institute reported that 25,000 Congolese (though not all refugees) were living in the US as of 2016. In 2018, 7,878 were admitted as refugees—the largest single group that year. The Trump administration has steadily slashed the number of refugees allowed into the country—for 2020 it has set a historically low limit of 18,000.

Those who want to become state-sanctioned refugees must apply through international organizations, and their cases generally trickle through bureaucracies and waitlists in a process than can last years. The few who are admitted (less than one percent of refugees worldwide have been resettled to designated host countries) are flown to US destination cities, where they are placed in an apartment or house and given financial assistance until they can find a job.

The vast majority of refugees around the world, however, are stuck in camps and other temporary living situations, often still well within reach of the violence that drove them from their homes. Gauthier and hundreds of other Congolese refugees were quickly losing hope for refugee resettlement. So they decided to try their luck and request asylum in the United States. But they had to get there first.

Gauthier, a single man, had escaped the DRC in 2017 and was living in hiding just outside the country. In the spring of 2019, he boarded a flight for Ecuador.

Once there, Gauthier and roughly 200 others began a grueling journey north. Some of them paused for a longer respite in Ecuador and Colombia. On the coast of Colombia, they split into smaller groups to board boats that transported them to Panama.

“There is much difficulty, much war. It has led to much death.” – Gauthier

From there, the travelers had to brave the Darién Gap, a grueling stretch of jungle and mountains separating Colombia and Panama. Some died in the dense tropical wilderness, where food and water were scarce and armed bandits lay in wait. Many of the migrants shared stories of rape, robbery, and violence throughout the journey, but especially in the Darién Gap.

Those who made it through followed a now well-trodden but perilous path through Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, and Mexico, hitching rides where they could, paying for bus rides when they had the money.

There would be only around 10 people in Gauthier’s group when he made it to San Antonio.

As he told his story, Gauthier fiddled with the paper wristband given to him by the City of San Antonio. It identified him as an immigrant, entitled to meals, restroom access, a help desk for logistical questions, and a bed at Travis Park Methodist Church.

Gauthier, who professes faith in Christ, wore a T-shirt from a student event at Community Bible Church, a local non-denominational megachurch. It read, “Students on a Mission.” Together, the wristband and the t-shirt told a lot about San Antonio’s response to the masses passing through.

As immigration-related crises and accompanying rhetoric have escalated in recent years, San Antonio has galvanized its stance as a city of welcome. At the forefront are a handful of Christian and other faith-based groups that, among other services, regularly house migrants released from nearby Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention centers.

Until the spring of 2019, it was rare for more than a couple of families or individuals to be stuck in San Antonio overnight while waiting for their next bus or plane. When the Del Rio substation began its catch-and-release policy, there were dozens every day.

Travis Park United Methodist Church is a mere three blocks from the Greyhound station where migrants—from Del Rio or one of the ICE detention centers just south of San Antonio— are dropped off after being released. Beginning in March, at 10 p.m. every night, the congregation opened its doors to migrants who needed a safe and relatively comfortable place to spend the night. Groups walked from the bus station, escorted by a local volunteer.

Gavin Rogers, an assistant pastor at Travis Park, has deep sympathy for the journey the migrants have been on. In November 2018 he flew to Mexico City to join the “caravan” of migrants moving north from Central America and see it for himself.

As in Del Rio, Travis Park quickly realized that the situation extended beyond what simple charity could accommodate. “Opening our doors to over 20,000 migrants was not possible alone,” Rogers said.

Travis Park, Catholic Charities, the San Antonio Food Bank, and the City of San Antonio formed a coalition to meet the various needs of those passing through San Antonio. In March the city opened the Migrant Resource Center in a former Quiznos sub shop between Travis Park and the bus station. Migrants there receive meals while city staff help them plan their next steps.

Usually travel arrangements are a prerequisite of release from ICE detention. But with detention centers overflowing, more and more migrants arrived in San Antonio without their next steps planned or funded. Along with overnight lodging at Travis Park, the coalition also helps pay for bus and train tickets and, in some cases, helps provide longer-term shelter needs.

As new waves arrive at the bus station, volunteers with a different group, the Interfaith Welcome Coalition, greet the wide-eyed travelers, accompany them to the ticket counter, and outfit them with backpacks full of the supplies they will need for the next leg of their journey.

Points In-Between

Gauthier boarded an evening bus bound for Memphis on June 29. He had a Subway sandwich, purchased with a donated gift card, to feed him on the 15-hour ride.

Upon arrival, strangers greeted him with food. The same happened again in Columbus, Ohio.

He didn’t know who the people were or what organization they were with, but he was grateful for the food. Three meals in three days was not a lot, but it wasn’t the hungriest he had been along the journey. During the passage through the jungles and mountains of Central America, he said, he went as many as five days without food.

Loose-knit groups of churches, advocates, and individual volunteers have been actively helping migrants at bus stations around the country. In 2018, a coalition calling itself Migration is Beautiful popped up in Memphis to lead the bus station ministry, though it appears to have disbanded. In Columbus, a Unitarian Universalist group leads the bus station initiative, marshaling donations and volunteers.

The groups are skittish about publicity. In San Antonio, a bus station official explained the pressure the groups are under to make the migrants as invisible and unobtrusive as possible to avoid confrontation.

“A lot of the people in here,” the official said, “don’t want these people here in the first place.”

Portland, Maine

The city of Portland, Maine, has made it clear it would welcome immigrants, just as it has for decades.

Since the Rwandan genocide in 1994, Jim King’s historic Charismatic Episcopal congregation has led efforts to aid refugees—both embracing them in Portland and assisting them abroad by, for example, helping widows access micro loans. In 2000, his Episcopal congregation joined the more conservative Charismatic Episcopal denomination out of respect for the growing African population in their membership.

King also founded a work program that allowed asylum-seekers to earn money toward legal services before they could be paid directly for their work. The African Service Co-op was eventually run by the immigrants themselves before being disbanded. Now, King said, this new wave of asylum seekers has him thinking of rebooting the co-op. He also works often with the Immigrant Welcome Center, a nonprofit business incubator and resource center run by two Congolese men who help newcomers start businesses, learn English, and find training for the many available jobs.

Maine’s population is aging, and the state has thousands of unfilled jobs in manufacturing, healthcare, hospitality, government agencies and education. Many see the summer migrant influx as a solution—but not one without hurdles.

The city was accustomed to taking on refugees, who had housing provided and permission to work. But when 370 Congolese and Angolans arrived from Texas in June, the city didn’t have the housing to care for them, nor could these asylum-seekers work until their cases had been settled. This was a new challenge.

As Portland residents debated the economic challenges of receiving so many refugees and their impact on public resources, the city opened its exposition center, “the Expo,” to hold families temporarily while they waited on housing. Gauthier was one of 450 immigrants who found themselves sleeping on cots in a gymnasium.

Meanwhile, in nearby Yarmouth, Maine, Carla Hunt was trying to scale another effort.

“While everyone else is figuring out the politics, we just want to help people while they are on their way,” Hunt said.

The religious identity of the African newcomers could not be more different: 80 percent of Congolese refugees admitted through the official US program identify as Protestant Christians.

Since 2015, the Yarmouth Compassionate Housing Initiative, based in the tiny city about 15 miles outside of Portland, had been pairing refugee and immigrant women and families with host families from its three member churches: First Universalist Church of Yarmouth, St. Bartholomew’s Episcopal Church, and a local Mormon congregation.

“What we had been doing, we had been doing very quietly underground,” Hunt explained. The groups had honed their process with about 40 families (150 individuals) before the city caught wind of them. “It gave us the chance to do our work without a lot of noise.”

Over the summer, the Yarmouth group housed about three families at a time, primarily those with newborns or medical issues that made the Expo unworkable. Increased visibility brought more volunteers, Hunt said, and ultimately inspired a group to fly down to San Antonio to see how that city was working with faith groups. Portland eventually modeled a Host Home initiative on the Yarmouth initiative, engaging faith groups as their primary partners.

“We think the faith groups are better equipped to do this quickly than people just doing this individually,” said Tom Bell, a spokesperson for the Greater Portland Council of Governments.

While the cooperation is mostly welcome, some evangelical churches in particular are skeptical. In a city like Portland, which is overwhelmingly secular, pastor Josh Phillips predicts a “boxing out” of churches wherever the city can meet needs.

Phillips, a former businessman and lay leader in The Village Church, was called from Dallas to Portland in 2014, when polls were ranking Maine as among the least religious states and Portland as one of the most biblically illiterate cities in the country. Those stats made it a chest-thumping kind of mission field, Philips explained. The reality, of course, was daunting. Seven of eight churches planted in the city that same year have since folded. Phillips’s church, Paupers’ Chapel, has around 35 regular attenders.

The religious identity of the African newcomers could not be more different: 80 percent of Congolese refugees admitted through the official US program identify as Protestant Christians.

Ruben Ruganza started the Philadelphia Church in Portland in 2009. The Pentecostal congregation has between 100-150 worshippers on Sundays, most of them immigrants. He had been the secretary general of the Community of Free Pentecostal Churches in Africa before he was forced to flee the DRC for the first time in 1996. It would not be the last. Over the next eight years, he left the DRC and returned several times, each time finding himself a target as violence erupted.

“More than ten times I escaped death,” he said matter-of-factly. Flanked by the books in his study and wearing an untucked button-up shirt, Ruganza has a gentle, easy demeanor. He’s long felt deep sympathy for refugees. “I have lived exactly the same life.”

While living in a refugee camp in Burundi, he began ministering to pygmy tribes and founded a ministry to help fund their education. He eventually made his way to the United States to fundraise for the organization, and it was while he was in Portland in 2007 that his wife called and told him not to come back, that soldiers had come to the camp looking for him. She and their five children joined him in Portland, where they were quickly granted asylum.

“I was very disappointed, to be honest,” he said. “I have a big community back in Africa. How can I stay here?”

It wasn’t that he didn’t love the United States. He said he has experienced great hospitality, even more than in African countries. “In Africa, the tribe matters,” said Ruganza, a Tutsi. “If you don’t belong to the same tribe, you don’t feel welcome.”

He felt that profoundly. Even thought the Tutsi has been a recognized tribe in the Congo regions for 300 years, he said, “still they say, ‘Go back to your country.’”

Even as Ruganza was saying those words, Gauthier, a countryman he had never met, was hearing the same phrase from the president of the United States. News outlets were buzzing about President Trump’s tweet that four mostly US-born congresswomen should “go back where they came from,” and many immigrants felt the comment’s sting.

Ruganza believes the animosity comes from a lack of understanding, but Gauthier disagrees. Recounting the perils of his journey, which like many immigrant stories has been thoroughly covered by the US media, he does not accept that anti-immigrant sentiment comes from ignorance.

“No, no, they understand. They are aware of everything,” he said. “They know that in Congo there are more than four million deaths. It’s not for nothing we are here.”

Gauthier is well aware of the long history between his homeland and western nations. Of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Of colonial and post-colonial power struggles over the DRC’s copper and rubber and precious minerals. All of which have helped to destabilize his country and, ultimately, contributed to the conditions that drove him to cross the world and two continents and step off a bus in New England.

The anti-immigrant sentiment was starting to chafe on Gauthier. After a month in the Expo, listening to Portlanders and Americans on television debate whether or not to help, a friend drove him into Canada and left him there.

For those who stay in Portland, Ruganza’s doors are open.

When he realized that he would likely be stuck in the United States for good, Ruganza felt God calling him to start a church in Portland.

“That was the worst idea I have had in my life,” he said, laughing. In Central Africa he oversaw 200 churches with half a million members. In Portland he began with seven worshippers. “It was like a joke,” he said.

Portland’s secular culture is a challenge, he said. In Africa, evangelism was the easy part; the real work was discipleship. In Portland, the struggle is just getting people in the door.

“But we have seen God working,” he said.

Bekah McNeel is immigrant communities editor for Christianity Today.