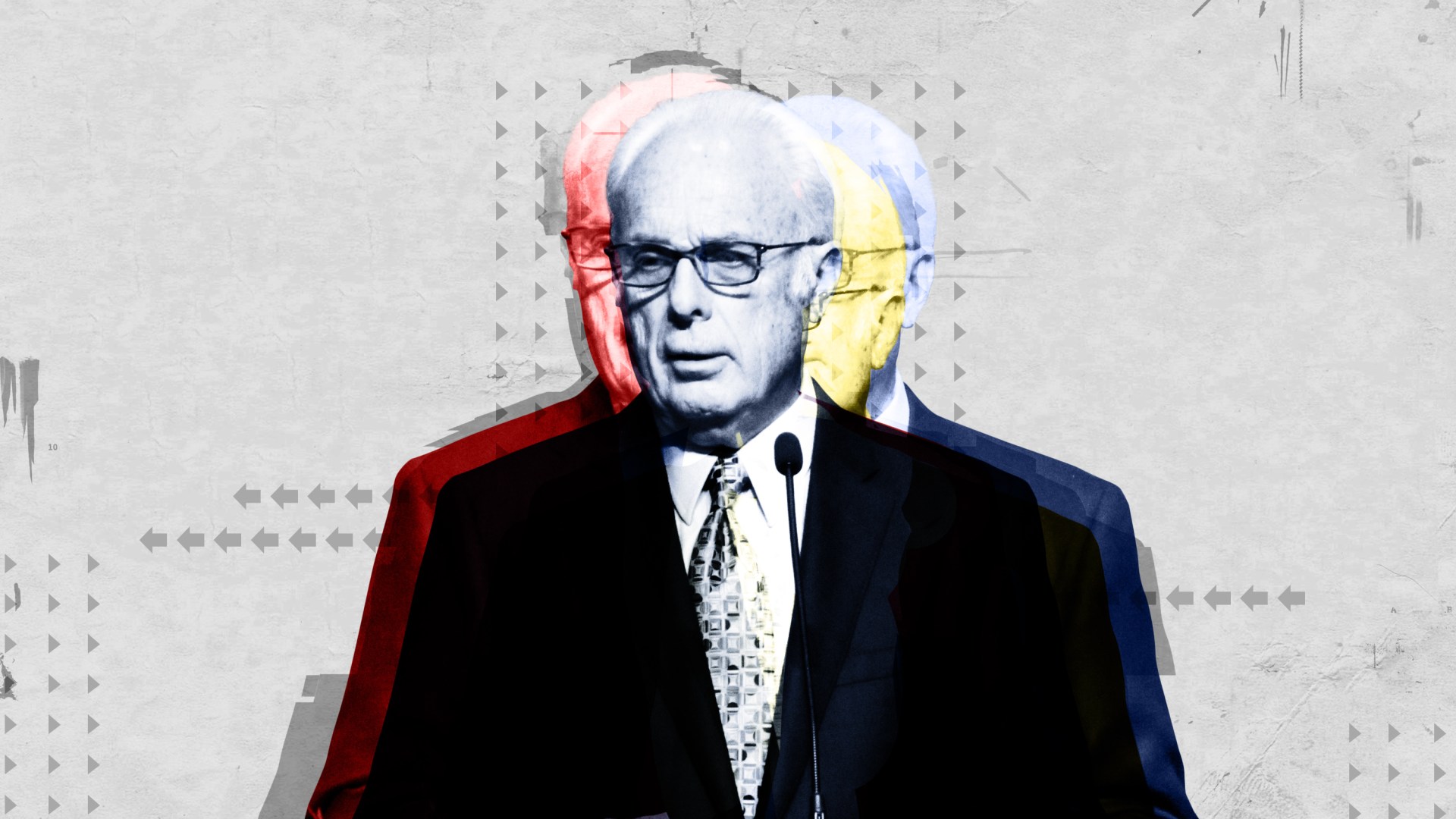

At his church’s recent “Truth Matters” conference, John MacArthur was asked to give a knee-jerk reaction to a series of words. The first was a name: Beth Moore.

“Go home,” MacArthur answered to the uproarious laughter of the crowd.

Predictably, social media exploded with responses to both castigate and defend MacArthur and Moore. Some delved into the larger debate context, started arguing for or against women preachers, and took a stance on MacArthur’s various derisive remarks on the topic. (His most notable one: “There is no case that can be made biblically for a woman preacher. Period. Paragraph. End of discussion.”)

However, what concerns me has less to do with the egalitarian and complementarian conversation. The hermeneutic that MacArthur so virulently defends—“We can’t let the culture exegete the Bible”—runs in glaring contradiction to his public comments. Despite his commitment to faithfully read Scripture, MacArthur (and others) often mistake this truth: In the Bible, home has never primarily been a woman’s place. In other words, when he says “go home,” he invokes a paradigm that isn’t biblical. Any church teaching that solely consigns women to the responsibilities of home (while tacitly excusing the men) proves exegetically paper-thin.

Some will say, of course, that I’ve assumed too much from MacArthur’s remarks. When he told Beth Moore to go home, we might assume that he meant simply to forbid Moore and women like her from preaching. But to listen to the entire audio clip is to see that MacArthur’s concern isn’t simply that women open God’s word publicly and explicate the text. The real danger, he reminds, is that they’re aspiring to hold positions of cultural power. They want to be senators, for goodness sake. Given this context, “go home” reaches far more broadly in its prohibitions. “Go home” is reasonably interpreted as the forbiddance of women aspiring to any role beyond wife and mother. No, “go home” isn’t just a debate about female preachers. It’s about women wanting to be doctors and lawyers, painters and poets, even President of the United States.

As proof text for women’s primary calling to the domestic sphere, MacArthur would likely point to Paul’s admonition in Titus 2, that younger women learn “to love their husbands and children, to be self-controlled, pure, working at home” (Titus 2:4-5). But this is not a culturally objective interpretation. Rather, the exegesis is western and modern.

History proves the point.

Prior to the Industrial Revolution in the West, the spheres of work and home were not as discretely divided as today, men leaving to earn the bacon, women staying to fry it. Homes were public places of industry and business as well as private residence. As Witold Rybczynski details in his book Home: A Short History of an Idea, only as families began separating home and work at the beginning of the seventeenth century did the home become a feminine space, a shift illustrated in domestic Dutch paintings at the time. “The Dutch were the first to choose ordinary women as their subject,” writes Rybcyznski. “The world of male work and male social life had moved elsewhere.”

In colonial America, home was a shared responsibility. The economic burdens of home did not fall solely to the men. In marriage, many women became their husbands’ economic partners and learned the necessary skills of their husbands’ work (butchering, silversmithing, upholstering). Likewise, the childrearing responsibilities, particularly the children’s spiritual “training and instruction” (Eph. 6:4), were not duties primarily assumed by the women. As a study of sermons during this time period bears out, the parenting advice doled out from the pulpit was addressed to men. (Incidentally, the cookbooks and home manuals of the era were also marketed to men.)

In her book, Just a Housewife: The Rise and Fall of Domesticity in America, historian Glenna Matthews cites seventeenth-century Puritan Cotton Mather in describing his approach to parenting: “I first beget in them a high opinion of their father’s love for him, and of his being best able to judge what shall be good for them.” Because industry was located in the home and its outbuildings and fields, fathers had an opportunity for direct and daily influence over their children. Men were not excused from the domestic sphere but held primarily responsible for it.

History exposes any defense of “traditional gender roles” as a doctrine far more recent than old. Titus 2 is one of the favorite passages of such “traditionalists” as MacArthur, but a close reading of it proves the striking similarities between the Titus 2 list of female virtues and the 1 Timothy 3 list of male elder qualifications. Just as women are called to the care of their families and homes in Titus 2, so too are the male elders in 1 Timothy: “The overseer is to be … faithful to his wife” and “manage his own family well and see that his children obey him,” for “if anyone does not know how to manage his own family, how can he take care of God’s church?” (1 Tim. 3:2-5). In fact, male elders have an additional domestic responsibility: the practice of hospitality, which is today often perceived as a feminine call.

In my own life, I’ve struggled for years to see my home as a space of shared calling. I was almost 27 when I had my first child, nearly 34 when I had my fifth. I was suckled on these “traditional” ideas of home. Even after acquiring a graduate degree, I accepted that my role was to sacrifice other vocational desires and instead prioritize the responsibility to care for my family. I supported my husband Ryan through eight years of professional exams and kept all the domestic plates spinning when he decided afterwards to pursue a different graduate degree.

When I did carve out time for some freelance writing projects in those early childrearing years, it was often in the predawn hours when my family would scarcely miss me. And though I nurtured small seedlings of ambition to do more biblical education, I seemed to implicitly understand that it would be my responsibility to figure out ways of making another graduate degree work. My primary role was to care for the children and to shield my husband (and his work) from disruption. We collectively abided the neat divide we’d been taught to honor: he at work, me at home.

Truthfully, I don’t regret having spent many years as a stay-at-home mom, waylaying the desire to write. My regret now is the impoverished way that Ryan and I imagined the work of the home. I regret that in those years, I mastered not the virtue of interdependence but the vice of self-reliance. For both myself and for my children, I regret the years that felt more like single parenting than co-laboring. When I tried exempting my husband from domestic burden, I prevented him from leaning in to his God-given responsibilities there.

Perhaps ironically, I’ve found myself nodding along when reading Matthews’ book about the history of the American housewife, which was published in 1987 in the wake of second-wave feminism. At the moment that women were being “liberated” from the drudgery of home, Matthews, a feminist scholar, did not tow her party’s line. Instead, the thrust of her book’s argument was subversive for its day. Making a home is a worthy endeavor, Matthews concluded. Let’s not denigrate the work; instead, let’s call everyone to it.

In an effort to respond to certain strident feminists and their incrimination of domestic desires and responsibilities, some Christians have made an error of their own kind. They have tried to elevate home and restore its respect by making it the highest calling to which women (and not men) can aspire. But our correction to them is not unlike the one that Matthews commended: Let’s continue to honor the work of home—but let’s call everyone to it.

Jen Pollock Michel is an author and speaker living in Toronto. Her second book, Keeping Place, explores the shared calling of home. Her third book, Surprised by Paradox, released in May.Speaking Out is Christianity Today’s guest opinion column and (unlike an editorial) does not necessarily represent the opinion of the magazine.