Fallout over a controversial documentary trailer rebuking an alleged social justice agenda within the Southern Baptist Convention marks the latest flashpoint in ongoing clashes over how the denomination should engage ideologies they see as contrary to Scripture.

Founders Ministries, a Calvinist-oriented Southern Baptist group, announced August 1 that three of its six board members had resigned over objections to the trailer for a forthcoming documentary titled By What Standard? Addressing recent debates over racial justice and women’s roles, the documentary alleges “wavering” commitment “to the authority and sufficiency” of the Bible among some Southern Baptists, the ministry said.

Two of the outgoing board members—Tom Hicks and Fred Malone—said in statements that they agree with the issues raised in the documentary but believe the trailer, which featured clips from the SBC annual meeting in June, conflated the problems with the denomination’s efforts to confront sexual abuse. (Initially, the four-minute trailer included an image of sexual abuse survivor and victim advocate Rachael Denhollander. After complaints, her clip was removed.)

The other resigning board member, Jon English Lee, did not release a statement.

Over the past year, two additional Founders board members had resigned, but the ministry’s president Tom Ascol said neither cited theological or philosophical differences among his reasons for departing.

At least three interviewees to be featured in the documentary—seminary president Daniel Akin, pastor Mark Dever, and author Jonathan Leeman—asked to be removed from the film over “concerns about what the tone, tenor, and content of the full documentary will be.” Several other participants took issue with the trailer.

These leaders do not represent opposite extremes of the nation’s largest Protestant denomination. The Southern Baptists taking issue with Founders’ approach share many core convictions with the ministry, not just the inerrancy of Scripture, but also an opposition to radical feminism and critical race theory dictating the church’s social engagement. A key difference among conservative Southern Baptists comes in how much they are willing to learn from elements of secular ideologies, versus rejecting them outright.

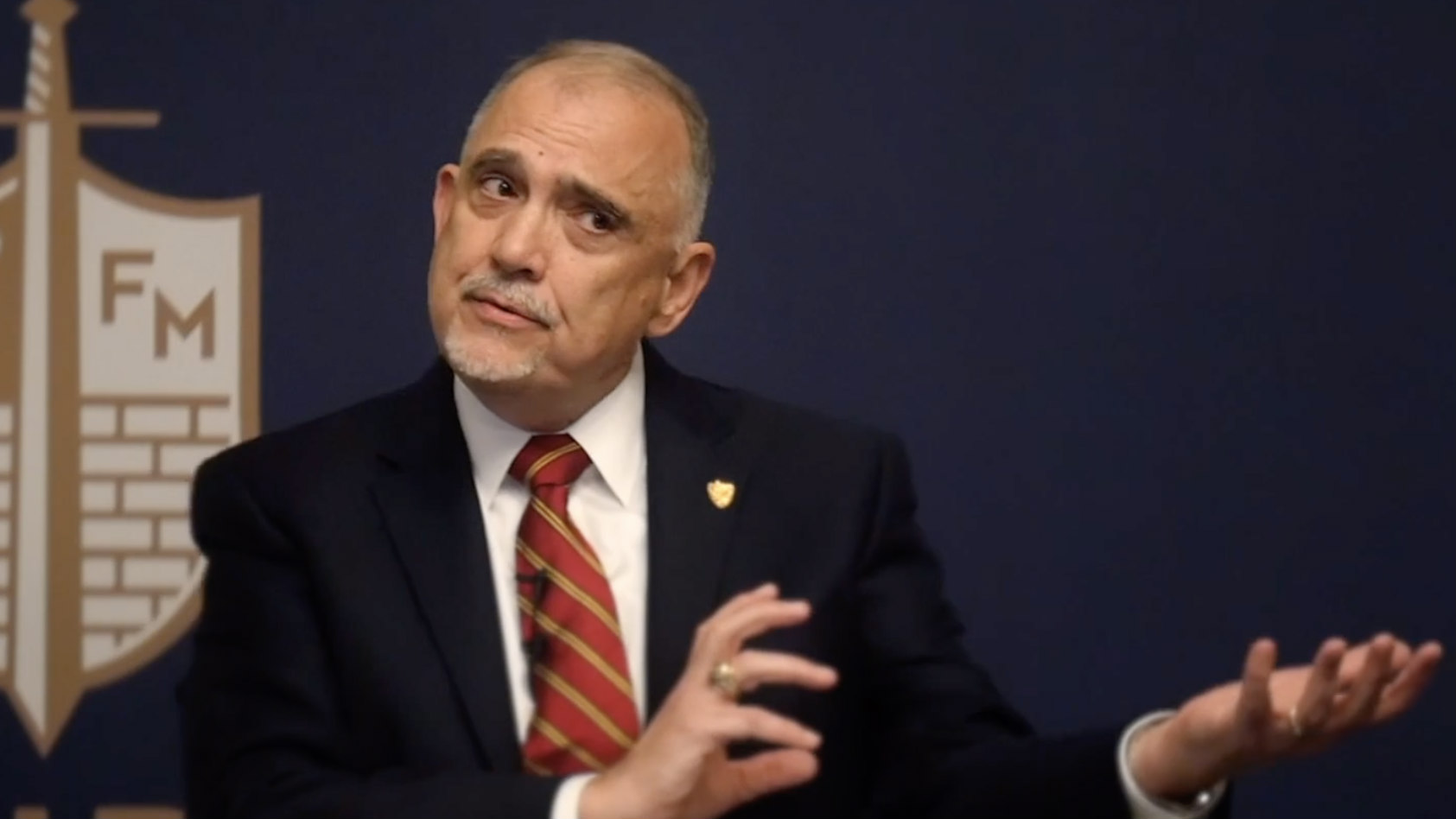

Ascol, pastor of Grace Baptist Church in Cape Coral, Florida, said reaction to the documentary illustrates how challenging it can be for Christians who agree on the inerrancy of Scripture and the exclusivity of the gospel to settle on a common strategy for confronting error in the culture.

Ascol told CT that everyone involved in the current SBC discussion is committed to Scripture, but there’s a divide between those who see learning from secular ideologies as a threat to the sufficiency of the Word and those who “think we can use the tools of these ideologies without getting burned by the ideologies themselves.”

‘Unaware’ of the danger?

The ideologies in question tend to involve race and gender, which have become hot topics among Southern Baptists in recent years, as the denomination continues to reckon with racism throughout its history and grapple with the proper application of complementarian teaching.

Despite relative agreement within the SBC on its statement of faith, The Baptist Faith and Message, different approaches on these social issues have come to the fore of Southern Baptist Convention over at least the past three years, dating back to disagreements around the 2016 presidential election.

More than 11,000 conservative evangelicals—many of them Southern Baptists—signed a 2018 “Statement on Social Justice and the Gospel” claiming “lectures on social issues” in the church and “activism aimed at reshaping the wider culture” “tend to become distractions that inevitably lead to departures from the gospel.”

Southern Baptists recently adopted a controversial resolution on critical race theory and intersectionality (CRT/I), which cited both theories as useful for confronting racial divisions even though the theories “have been appropriated by individuals with worldviews that are contrary to the Christian faith.”

Members of the denomination were split: “Some Southern Baptists claim insights from CRT/I can be appropriated to understand the plight of victimized populations and to more effectively approach them with the gospel,” the Southern Baptist Texan reported. “Others say the theories’ origins—typically ascribed to postmodernism and to neo-Marxism—undermine their usefulness for believers.”

A Twitter discussion over women like Beth Moore preaching in public worship stirred up among Southern Baptists last spring and led to a formal debate on the topic at a Founders meeting in June between Ascol and Texas pastor Dwight McKissic, who has also taken issue with his portrayal in the documentary trailer.

Thanks to the internet, the Southern Baptist back-and-forth over how to engage social issues is happening in real time and before the church and the watching world. At the same time, top entity leaders and pastors have sought to address major cultural moments from a biblical perspective, rather than letting secular or leftist ideology drive discussion.

The denomination has been here before. Southern Baptist Theological Seminary President Albert Mohler recognizes the “massive cultural upheavals” today’s church faces, and he recalls a resistance to liberal theology in the 1970s that instituted the SBC’s Conservative Resurgence.

“There is anxiety … that a younger generation is unaware of many of the same dangers” that led the SBC leftward in the past “and perhaps unaware of the extent to which many of the larger currents in the culture have been embraced,” he told CT.

Mohler has distanced himself from the Founders’ documentary and said he does not believe there is an ideological commitment to “leftist doctrines” in the SBC, no conscious efforts to move the denomination away from Scripture.

‘Wresting with’ social justice

Looking back even further than the Conservative Resurgence, the conflict over cultural engagement in the SBC is nothing new, according to Carol Holcomb, a University of Mary Hardin-Baylor University professor who studies Baptists and the social gospel.

Ever since social gospel teaching emerged in the early 20th century, the SBC has alternately embraced and denounced it. Southern Baptists’ reticence to devote themselves fully to social causes, Holcomb told CT, stems in part from early Southern Baptists’ desire to defend slavery. The convention’s founders devised an “elaborate defense of slavery” in the mid-19th century “that divorced individual from social sin” and caused the SBC to develop “a religious culture” that “is inhospitable to social justice.” While support of slavery dissipated long ago, she said, residual resistance to social causes remains.

Though Southern Baptists long have cared about social ills, Holcomb said, their theological heritage makes it difficult for them “to find the gospel of the both/and”—embracing the idea “that Jesus cares about the whole person” and not merely salvation of the soul. Some focus more heavily on individual salvation while others include a greater emphasis on social ministry with their evangelistic efforts, she said.

Framers of The Baptist Faith and Message apparently viewed social ministry and evangelism as complementary rather than in tension. The SBC’s faith statement champions both the duty “to make disciples of all nations” and the “obligation to seek to make the will of Christ supreme in our own lives and in human society.”

For Ascol, the issue is faithfulness to Scripture. He fears that some Southern Baptists, while committed in theory to inerrancy, are allowing ideologies other than Scripture to determine their beliefs and practices in the church.

For example, he said, the Bible states qualifications for pastors in 1 Timothy 3:1–7, but some undermine Scripture’s sufficiency by claiming a preacher isn’t qualified to state the Bible’s teaching on race unless he also studies extensively the experience of ethnic minorities. Similarly, Scripture presents plain teaching about gender roles, but some claim that teaching cannot be understood without studying extensively the experience of being female.

“It can be a very good thing” to seek understanding of other believers’ experiences, Ascol said. “But to suggest” that “we somehow cannot know truth unless we do this” implies “the Bible really is not sufficient.”

Additionally, voices concerned about the place of social justice initiatives in the church worry that such priorities could divert efforts away from evangelism and Christian mission.

Mark Coppenger, a retired philosophy and ethics professor at Southern Seminary, said, “A good many evangelicals seem to think … by ingratiating themselves to the culture (or at least not turning it off), they’ll see a harvest of both goodwill and kingdom growth.”

Yet some advocates of social justice see it as an expression of Christian teaching and mission.

Kevin Smith, executive director of the Baptist Convention of Maryland-Delaware, where some 500 churches worship in 41 different languages, said varying approaches to cultural engagement should not disrupt the fellowship of believers, like Southern Baptists, who “agree on the person and work of Jesus.”

“At least half of what’s going on among Christians is not even about the content and the disagreement of the matter, but is about sinful, divisive personality, ethnocentrism, political convictions, and overzealous arrogance,” Smith said. “Another half is disagreeing over how we apply loving our neighbor.”

The SBC is not alone in discussing the way forward for believers amid cultural challenges. The Gospel Coalition, a parachurch group of Reformed evangelicals, has faced similar discussions, and a much-discussed exchange at Bible teacher John MacArthur’s Shepherds’ Conference earlier this year also addressed social justice.

David Roach is a writer in Nashville, Tennessee.