These days, living in small-town America often means living with less.

2018 marked another year of decline in many rural and small towns: economies suffering; local residents aging or moving away; and many struggling with addiction, disillusionment, or depression.

But just as the nation declares a crisis in small communities, the church has seen new momentum around rural ministry. Proud pastors from blue-collar outskirts, flyover country farmlands, and cozy mountain towns proclaim that in God’s kingdom, less is more.

In new books, blogs, networks, and conferences, these leaders resist popular narratives about rural America to instead embrace the gospel lessons they encounter when doing ministry on a small scale.

“One of the things that the rural church reminds the global church of is God’s commitment to be with people everywhere. We as the people of God have been sent to the ends of the earth and sometimes rural is one of those ends,” said Brad Roth, pastor of West Zion Mennonite Church in Moundridge, Kansas.

“Not every place is going to have the same potential for that growth metric. But every place is still beloved by God and worthy of our best and most thoughtful ministry as the church.”

While plenty of materials are geared toward church growth in bigger congregations, more resources are emerging for leaders in smaller contexts. America’s largest Protestant denomination, the Southern Baptist Convention, dedicated its annual pastors’ conference—long the domain of megachurch pastors—to small-church pastors in 2017.

“Despite rapid global urbanization, many millions around the world continue to live in small towns and rural areas. God is calling some of us to live and minister in these places,” read the announcement for a Small Town Summits event to coincide with The Gospel Coalition’s national conference in April. “More than that, he’s calling us to love small places, to see them as simultaneously more delightful and more desperately needy than our wider culture does.”

God is glorified through sermons preached in obscure pulpits. ~ David Pinckney

Small-town pastors know how to look beyond declining numbers to love their communities for something besides productivity and potential. After all, in their own ministries, they’ve had to gauge success beyond membership figures and tithing income—much less their own prominence.

Last fall, Acts 29 launched its Rural Collective, designed to equip congregations in sparse, isolated areas to become churches that plant others. In the words of the collective’s co-director, New Hampshire pastor David Pinckney, “Rural churches are often small and mostly unnoticed. Yet God is glorified through sermons preached in obscure pulpits.”

Churches’ community impact is amplified in such places, where there may be only a few houses of worship or even just a single Bible-believing congregation.

“If you blow it, your public witness is diminished a lot more quickly,” said Stephen Witmer, lead pastor of Pepperell Christian Fellowship, a 200-person congregation in a 12,000-person town an hour outside of Boston. “But if you’re kind, invested, and involved, you can become a pastor of a community.”

Witmer and his partners at Small Town Summits want to develop a theological vision for rural churches, just as urban churches have been spurred by TGC co-founder Tim Keller’s call to love the city. Around 1 in 5 Americans, 60 million people, live in rural areas.

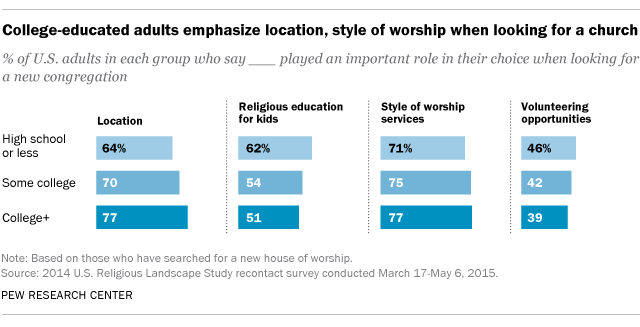

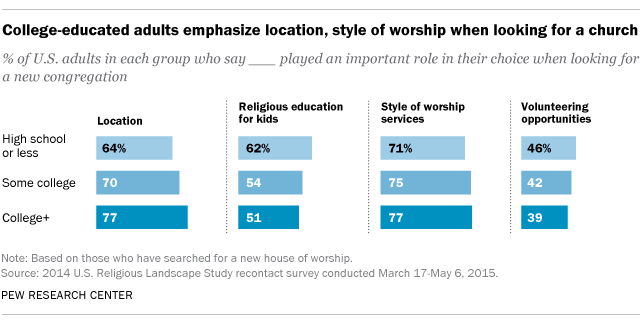

Americans are now less inclined than ever to move for jobs. Recent analysis by the Pew Research Center found that blue-collar families generally stay put in their houses of worship, too; just 38 percent of those with a high school education or less have had to church shop, compared to 59 percent of those with a college degree.

“We have people who will stay forever,” said Hannah Anderson, who has written about rural ministry. At her Baptist congregation in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia, some members have attended for generations.

Among churches that feel like family—because they literally are family—this sense of longevity can help put ministry struggles in perspective. “There’s less pressure for you to be on the cutting edge,” said Anderson, author of Humble Roots. “What you’re doing is maintaining the flame. You’re not the one that has to create something because you inherit a history.”

Small towns are also aging. The New York Times reported that the median age in rural America is 43, seven years older than the rest of the country. Kansas pastor Roth noted that in the past year, his church has lost more members to death than to folks choosing to leave.

The demographic shift often leaves an age gap. “Most of our people are above 50 and so when young families visit, they affirm that they love the church and the messages and that we were friendly, but they wanted to attend a church that has more young families,” said Glenn Daman, pastor of River Christian Church, which draws about 80 people in Stevenson, Washington.

Blue-collar adults were more likely than college-educated adults to prioritize children’s ministry, 62 percent compared to 51 percent, according to Pew.

Though rural churches hope to welcome the occasional visitors in more-closed communities or the wave of new residents that may come when a new industry comes to town, their day-to-day priorities tend to put depth over breadth.

“For me, our metric is always Christlikeness,” said Roth, author of God’s Country: Faith, Hope, and the Future of the Rural Church. “The life of the church is always a little bit immeasurable. What we’re doing doesn’t always have a number that is trackable. The world at large doesn’t always get that.”

When there are just a few dozen people in a congregation, and maybe just one or two people on staff, pastors cannot afford to emulate bigger churches or attractional ministry models.

“In small churches, the focus is upon relational cohesion and connectedness whereas in larger churches the focus is more upon program development and quality,” said Daman, who directs the Center for Leadership Development for Village Missions, a ministry supporting country churches.

Pastors in small places see the value of their ministry, despite demographic shifts that point to further decline.

“When the gospel is brought to a place that has no strategic value, they’ve gone there because God has gone to us,” said Witmer, whose book, A Big Gospel in Small Places, releases this fall.

Witmer and fellow leaders are cautious about idyllic country stereotypes. Their ministry is not easy or carefree—especially in places where numbers dwindle and economic opportunities tighten—but the Lord calls them there just the same.

“If trends continue and more and more people migrate from rural communities to urban centers, we envision two things. First, we see those who have met Jesus and grown in gospel joy in their villages and towns moving as missionaries to major cities,” the leaders of Acts 29’s new Rural Collective wrote.

“Second, we believe that those who will never leave their dusty roads and remote settings ought to have accessible gospel community for the glory of God and the good of their neighbors.”

Kate Shellnutt is associate online editor at

Christianity Today

.

Have something to say about this topic? Let us know here.