Pope Francis must love creating cognitive dissonance.

This week, he became the first Catholic pontiff to ever visit the Arabian Peninsula, the heart of Islam, where conversion to Christianity is illegal. Francis lauded his hosts in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), saying they “strive to be a model for coexistence.”

The Gulf nation’s crown prince received him with a 21-gun salute. Francis then railed against the “miserable crudeness” of war.

Human rights groups pressed him to address migrant worker issues. Francis rejoiced in “a diversity that the Holy Spirit loves and wants to harmonize ever more, in order to make a symphony.”

The mere existence of a Christian community to visit in the Gulf states may surprise many. In 2015, CT visited the Emirates and reported on its “thriving” church, populated by more than a million Christians—primarily economic migrants from Asian nations such as Indonesia and the Philippines.

The Pew Research Center counts them as 13 percent of the population. They worship in over 40 churches, served by over 700 Christian ministries.

And in a region where the Vatican cited a decline of Christians from 20 percent to 4 percent of the Middle East population in the last 100 years, the Emirati government provided a day off and 1,000 buses to bring Catholics to mass.

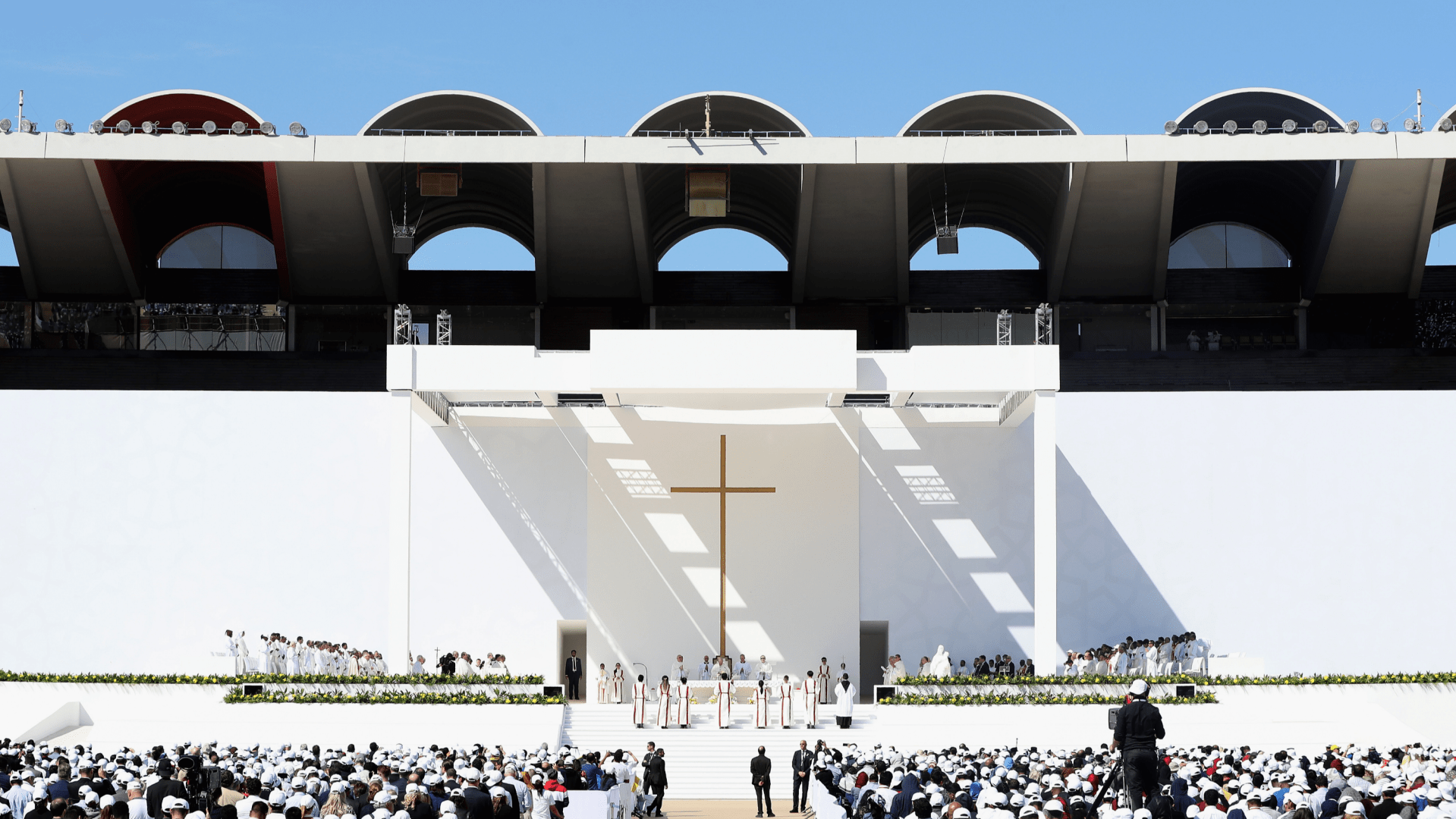

Attendance reached 135,000, billed as the largest Christian gathering ever held in the Arabian Peninsula.

If the pope does enjoy sparking controversy, he succeeded also among local evangelical leaders.

“The mass was amazing. I never believed I would witness anything like that in the UAE,” said Jim Burgess, pastor of Fellowship Church and member of the Gulf Churches Fellowship, where he represents independent churches among the region’s senior ecumenical clergy.

“Obviously, the pope’s visit raises respect for Catholics. But when Protestants—even evangelicals—link arms with Catholics and say, ‘We follow Jesus,’ I believe it helps all Christians here.”

Not everyone agrees.

“We are grateful for any religious openness in a Muslim society,” cited one evangelical leader, who requested anonymity. “At the same time, we do not regard the papal mass as true Christian worship because the official Roman Catholic Church teaches a different gospel.”

One Christian commentator found possible evidence of this in Francis’ interfaith work. At the largest mosque in Abu Dhabi, he signed the Declaration on Human Fraternity, joining Ahmed el-Tayyeb, Grand Imam of Egypt’s al-Azhar, and head of an international Council of Muslim Elders.

Afterwards, the crown prince broke ground on a new church and new mosque, built side by side in Dubai and named in honor of the signatories.

“The pluralism and the diversity of religions … are willed by God in His wisdom, through which He created human beings,” it said. The phrase parallels a concept found in the Qur’an, in which God intended a multiplicity of world faiths.

Yet even here there is dissonance, for the section continues, “therefore, the fact that people are forced to adhere to a certain religion … must be rejected.”

Pope Francis intended his visit to serve Christian minorities in the Muslim world, but also buttress freedom in general.

“As part of such freedom, I would like to emphasize religious freedom,” said Francis. “It is not limited only to freedom of worship but sees in the other … a child of my own humanity whom God leaves free and whom, therefore, no human institution can coerce, not even in God’s name.”

The conference afforded Bishop Ephraim Tendero, secretary general of the World Evangelical Alliance, to endorse the importance of dialogue and peace-building.

But he ended by speaking creatively about conversion.

“At earlier points in history, Christians have sometimes taken harder stances toward people who abandoned the Christian faith,” he told the gathering.

“But we have come to realize that forced religious belief is no belief at all.”

The New York Times was more direct, stating that proselytizing against and conversion from Islam is illegal in the UAE. The Associated Press noted restrictions on religious freedom for Muslims, intertwined with political issues.

Open Doors ranks the UAE at No. 45 on its World Watch List of the 50 nations where it is hardest to be a Christian—primarily because of difficulties faced by converts.

In contrast to “freedom,” the UAE government has proclaimed 2019 as the Year of Tolerance—praising Pope Francis as its symbol, and itself as an example.

“The pope’s visit will send a strong signal across the region and world,” said Yousef Al Otaiba, the UAE’s ambassador to the United States, to The Guardian newspaper. “People with different beliefs can live, work, and worship together.”

And nearly all Christians in the Emirates celebrate this, though to different degrees.

“The religious freedom we enjoy here is fantastic,” said Ani Xavier, parish priest of St Paul’s Church in Abu Dhabi. “Everyone is respected. We are given land and the rulers are excellent.”

While official relations with the Vatican did not begin until 2007, the first Catholic church was built in 1965. In 1970, Abu Dhabi became the see of the Apostolic Vicariate of Southern Arabia, and today supervises 100 priests for 2 million Catholics across the peninsula.

Otaiba also wrote an op-ed in Politico praising the two American missionary doctors who came in 1960 and opened the first hospital. To this day, it freely distributes Bibles and Christian materials.

“l don't believe what we have here is religious freedom; it is religious tolerance,” said Burgess. It permits his church to welcome 4,000 people from 90 nationalities during six weekly services in two hotels.

“However, that’s saying a lot. Church leaders in the UAE are very appreciative of what the government is doing to make a place for us in the Muslim country.”

But in past years, a few Christians in the UAE have been arrested, imprisoned, and deported for sharing the gospel, said the anonymous evangelical leader.

“What does ‘tolerance’ mean in a country where conversion is illegal?” he said. “But the government has extended privileges to expatriate Christians, and for that we are grateful.”

The privileges have resonated with the UAE population. A poll conducted by YouGov on behalf of the Muslim Council of Elders found that only 13 percent of Emiratis believed that Christianity clashed with the values of their country. The same percentage held unfavorable views toward the faith.

But in Germany and France, half believe Islam clashes with their civilization, with the same unfavorability rating. In the US and the United Kingdom, one-third held this view, with 37 percent and 32 percent respectively unfavorable to Islam.

Neighboring Saudi Arabia registered closer numbers to the West, with 25 percent seeing a clash and 42 percent feeling unfavorable toward Christianity.

Perhaps the pope will encourage them also? A Saudi daily featured a headline wondering if Francis will visit them soon.

“We still have a long way to go in the Arabian Gulf,” said Burgess. “But the world needs to know a place like this exists.”

It exists in large part due to prosperity, according to US ambassador-at-large for international religious freedom Sam Brownback. Millions of dollars are transferred as remittances by migrant workers, helping their impoverished families back home.

Brownback “saluted” UAE leadership over the pope’s visit and was “impressed” by the joint declaration with al-Azhar.

“Moving it into action is a key point,” he told CT on a conference call. “But they have realized that diversity of thought and different religions are an important way of growing their economy.”

Brownback aims to further stimulate reforms through upcoming regional religious summits, as well as the second State Department Ministerial to Advance Religious Freedom, to be held in DC in July.

Brownback is not the only American to praise the Emirates, and Christian outreach is not limited to Catholics. Joel Rosenberg previously led a delegation of evangelicals to visit the UAE crown prince, finding “a hidden treasure of moderation.”

But once cognitive dissonance settles, a certain nuance settles in.

“It’s not an American model of religious freedom for everyone,” said delegation member Jerry Johnson, president of the National Religious Broadcasters, specifically mentioning freedom of speech.

“But they're moving in a very good direction, and this would be a great model for the area.”