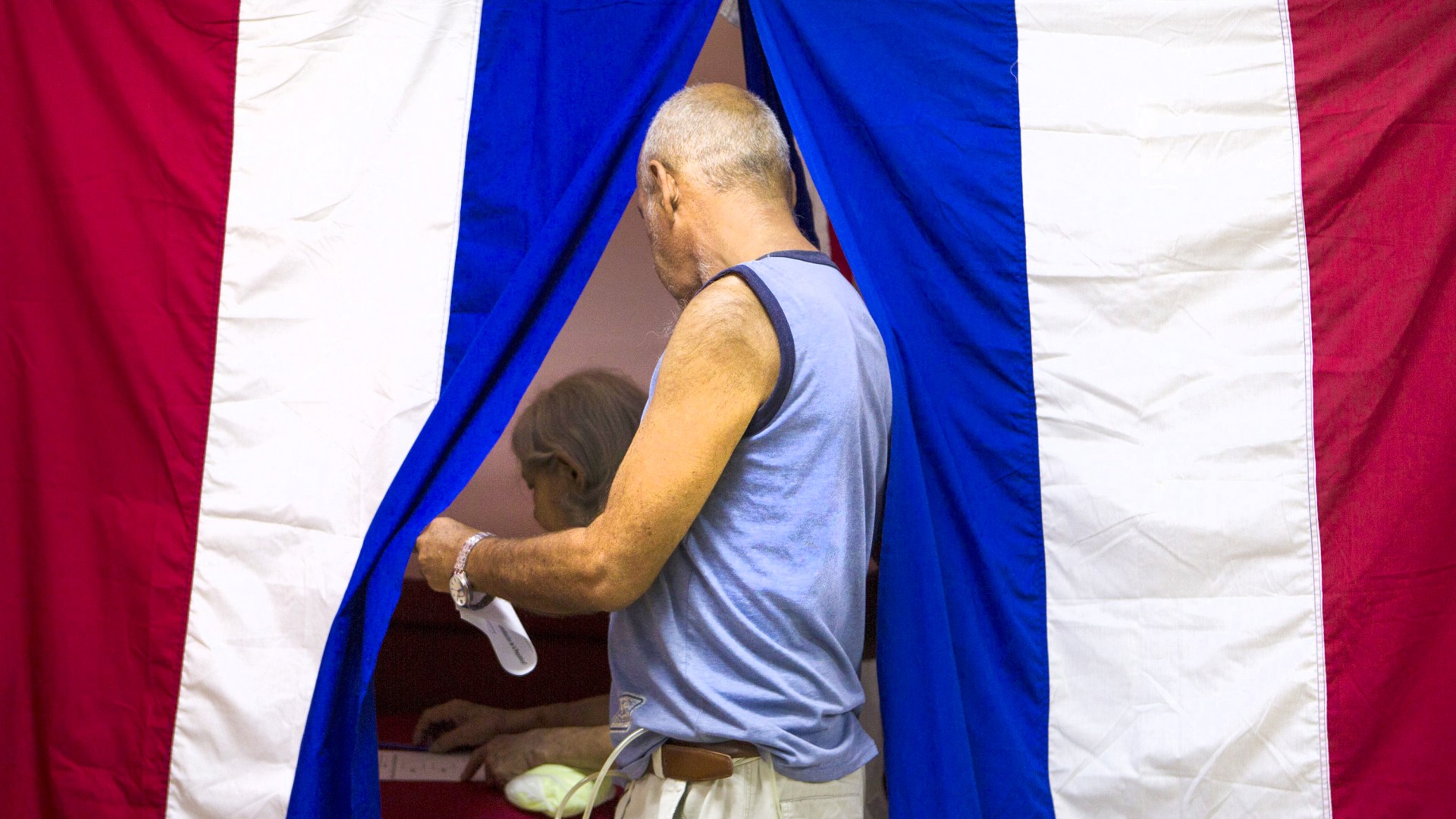

As Cubans voted to approve a new constitution on Sunday, widespread Christian opposition may signal a shift in political tone and a new sense of unity among the island’s churches.

The grassroots campaign—formed largely against more permissive language regarding same-sex marriage—earned Christians a measure of political clout in the island nation, but for some it’s also garnered them a reputation as enemies of the state.

“I can’t vote for something that goes against my principles,” Alida Leon, a pastor and president of the Evangelical League of Cuba, told the Associated Press. “It’s sad but it’s a reality.”

“I am voting ‘no’ because taking out that marriage is between a man and a woman opens the door in the future to something that goes against our beliefs and the Bible,” another Baptist pastor in Havana told Christian Today.

In a demonstration earlier this month, at least 100 couples decked in suits and wedding dresses gathered in the capital to renew their vows and to protest redefining marriage in the constitution.

“We’re speaking out in favor of marriage as it was originally designed,” Methodist Church of Cuba bishop Ricardo Pereira said. “It’s the first time since the triumph of the revolution that evangelical churches have created a unified front. It’s historic.”

The government and its loyalists tried to turn the vote into a litmus test for patriotism, instigating a sprawling advertising campaign to promote the new constitution. But Christians’ counter-campaign proved too big to stifle.

The opposition first erupted last year when churches began to hang banners and print flyers espousing a traditional view of marriage. The large-scale coordinated campaign also included delivering a petition with 178,000 signatures rejecting the legalization of gay marriage to the Cuban government.

Public consultations also revealed strong opposition to Article 68, the portion of the constitution offering a new definition of marriage.

Because of that pressure, a level of resistance rarely seen in the 60 years since the Cuban Revolution, Cuba’s National Assembly walked back language that changed the definition of marriage as between a man and a woman to “between two people.”

The revision came as a major blow to the national LGBT rights campaign conducted by Mariela Castro’s National Center for Sex Education and other activists. In response to their denouncement, Castro, daughter of former president Raúl Castro, called the Catholic Church “the serpent of history” in a Facebook statement and bid a strong state response.

Rather than revert to the previous wording, marriage language was left conspicuously absent from the revised document, clearing the way for future legalization efforts. Even with the door open for a later policy change, the reversal marked a win for Cuba’s growing evangelical population.

“Looking at how they’ve managed to derail gay marriage from the constitution, it’s clear the evangelicals have become a major political force,” Javier Corrales, political science professor at Amherst College, told the Guardian.

Christians also expressed intense frustration with the new constitution for softening religious freedom protections, limiting access to education and media, and barring financial investments among native Cubans. Language defending the “freedom of conscience” that had been stated explicitly in the previous constitution had also been eliminated.

Several church groups, including the Eastern Baptist Convention, the Methodist Church of Cuba, and the Assemblies of God issued public statements criticizing the proposed constitution. Catholic churches in Cuba went as far as reading a four-point critique at Sunday masses.

Though initial reports on Monday indicate that Cubans “overwhelmingly” voted to ratify the new constitution, experts predicted around 70 percent to 80 percent were in favor, down from the 97.8 percent that approved the island’s previous constitution in 1976.

Such near-unanimous votes are customary for the communist-led government, but things are changing. In a country where national atheism was long considered legal policy, Cuban Christians’ influence is growing. The way they use their place to pressure policymakers and express public dissent could have serious ramifications, particularly as the political class views their unprecedented opposition as a dangerous turn.

Despite the near-certainty that the referendum would pass, Christians still faced threatening treatment for their public opposition leading up to the vote.

Last week, Carlos Sebastián Hernández, president of Western Baptist Convention, received a call from Sonia García García, deputy head of Cuba’s Office of Religious Affairs, in which García García reportedly said he “will no longer be treated as a pastor, but as a counter-revolutionary.”

“I have total confidence that, even in Cuba, God reigns. Pray for me and my family,” Sebastián Hernández told CSW, a UK-based charity defending Christians against persecution. “My wife and I have spoken and prayed because at any moment they could take me prisoner.”

Other pastors have reported their homes being surrounded by state security forces, receiving threatening phone calls warning of imprisonment if they don’t call their congregations to vote in favor of the referendum, being labeled “mercenaries,” and other forms of intimidation.

“The church has had no rest in these days,” another denominational leader who received a threatening call from García García told CSW. “They are besieging and intimidating us just for defending our rights and our principles.”

“The Cuban government must immediately cease its attempts to intimidate and pressure religious leaders and their congregations as the country prepares to vote on Sunday,” Anna-Lee Stangl, CSW’s Americas team leader, said last week, echoing similar calls from the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom and others.

“As church leaders have repeatedly pointed out, the government largely ignored their requests and recommendations during the period of national consultation on the draft constitution specifically with regards to freedom of religion or belief and freedom of conscience. It is telling that the Cuban government considers calling for freedom of religion or belief a ‘counter-revolutionary’ activity.”

But even as many Cuban Christians have been vilified by the government, they’ve been lionized by one another. Historically, denominations and churches in Cuba have not formed strong united fronts. Amid recent struggles and shared pressure from the state, that may be changing too.

Between 5 and 10 percent of Cubans consider themselves evangelicals and as many as 70 percent associate with Roman Catholicism, sometimes of a syncretistic variety. While unity has been lacking in recent decades, opposition to elements of the new constitution made allies of Methodists, Baptists, Pentecostals, Assemblies of God churches, and many in the Catholic Church.

While the referendum passed, this significant and unified show of dissent may be the first decisive move of Cuban Christianity, especially evangelicalism, on the modern political stage.

CT reported in 2015 on evangelicals’ revival in Cuba as the country renewed diplomatic ties with the US, as well as the death of longtime leader Fidel Castro, which ultimately had little impact on the island’s religious landscape.