Update (Feb. 1): “Hooray! The church is closed,” declared a sign on the door to Bethel Church in the Netherlands this week.

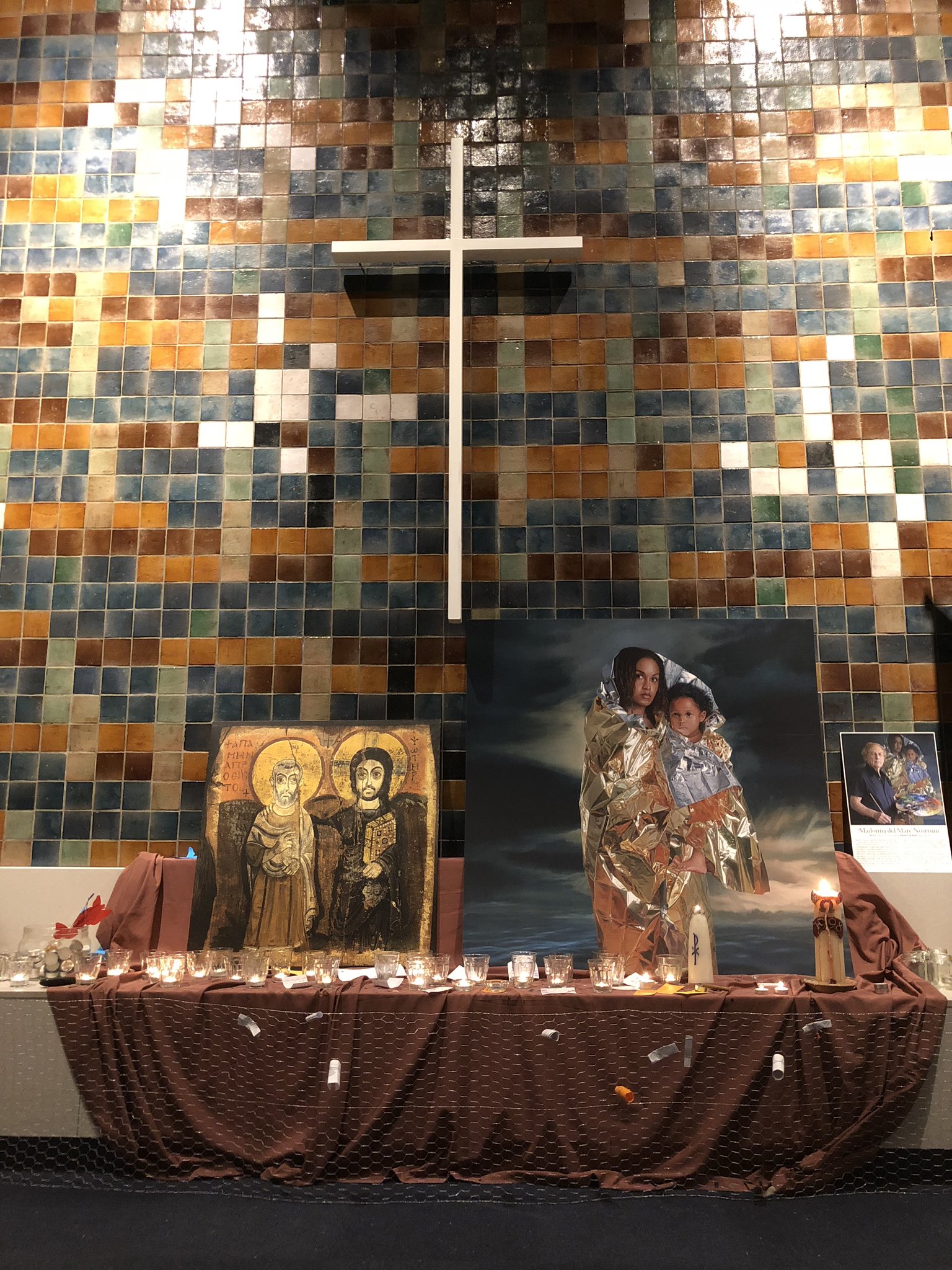

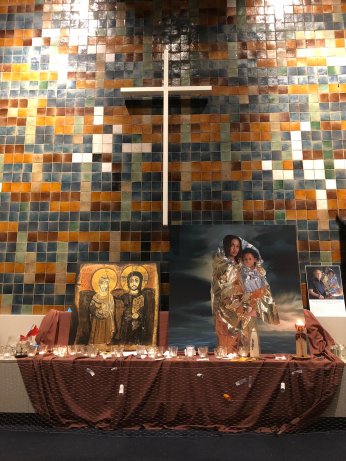

This sanctuary in The Hague emptied for the first time in more than three months after a continuous church service held to protect a refugee family from deportation finally came to an end, following a government compromise in their favor.

The New York Times called the 96-day gathering at the Dutch church “one of the longest religious ceremonies ever recorded,” enlisting nearly 1,000 pastors across denominations to participate.

The Dutch government is generally prohibited from interrupting religious services, so the Protestant congregation kept extending their gathering during the debate over family asylum or kinderpardon. Officials agreed to allow the Armenian family at Bethel—along with 700 others who have lived in the country for more than a decade—to have their cases reviewed again rather than facing immediate expulsion.

Bethel has committed to continue praying for the family’s security and status, but ended the 24/7 service. With the final amen, the pastor extinguished a candle on the altar after keeping one burning there for over 2,300 hours.

“When we started we had nothing, only our faith,” Dutch theologian Theo Hettema said as the marathon service concluded. “It proved amply sufficient.”

—

Original post (Dec. 5): A marathon worship service held by a church in the Netherlands to shield a family of asylum seekers has garnered worldwide attention. The feat has proved impressive for its longevity alone—now going on six weeks—but also represents a unique ecumenical moment among Christians in the tiny European nation.

Dutch law generally prohibits officials from interrupting a religious service, so Bethel Church in The Hague has kept worship going non-stop in order to turn its church into a sanctuary for an Armenian family who face expulsion. The congregation—part of the Protestant Church of The Hague and the country’s largest denomination, the Protestant Church of The Netherlands (PKN)—could not pull off the almost 1,000 hours of worship on its own, so its leaders have tapped more than 500 pastors from across traditions to participate.

“What this church asylum is teaching me in the first place is how enormously connecting and boundary-shattering the most basic compassion can be,” Axel Wicke, a pastor at Bethel, told CT.

“Here in the Netherlands, we have a huge amount of different Christian confessions, some of which originating in very ugly theological or liturgical fights. However, here at the church asylum in Bethel, none of this matters and everyone is working together…,” he said. “Very often, one pastor hands over the service to another colleague, with whom he would never be able to share anything else, either theologically or liturgically.”

The service has brought together not only PKN pastors—who, after a 2004 merger, represent most Reformed and Lutheran churches in the Netherlands and about 9 percent of the population overall—but also smaller denominations. Organizers list Pentecostals, Baptists, and Orthodox Reformed leaders among the participants, along with Catholics.

Jan Wolsheimer, the new director of Missie Nederland, the national evangelical council, has led the service repeatedly since the efforts kicked off on October 26 and has promoted the cause on social media.

The efforts center around the Tamrazyan family, who have lived in the Netherlands as political refugees for nine years and whose court-ordered asylum status was overturned. They’re now awaiting a kinderpardon or “children’s pardon,” which allows families with kids who have lived in the country for more than five years to stay legally.

The Tamrazyans represent an estimated 400 families across the Netherlands who await similar protections; news reports indicate just 100 of 1,360 requests for kinderpardon have been grantd in the past five years.

“As almost any topic among Dutch Christians, there is a broad variety of stances on the issue of kinderpardon,” Wolsheimer told CT. “Maybe not so much on the amnesty for the children involved, where most Christians agree on, but the way the church uses the church service to create asylum divides them.”

Wolsheimer, who used to pastor an evangelical congregation in Woerden, referenced a divide among evangelical Christians and theologians over whether the asylum service taints worship with political activism.

On his blog last month, he urged concerned critics to reconsider, writing that the service remained solemn and focused on the Lord, without the distraction of crowds, banners, or political campaigning. He said the efforts reflected the pursuit of justice described in Amos 5.

Ultimately, “Some critics joined in for a service and met with the Tamrazyan family and changed their stance; others sympathized with the family but still rejected the use of the church service to keep this painful situation in view,” he told CT.

Christian newspaper Nederlands Dagblad reports that prior to being taken in by Bethel, the family spent a few weeks at an Orthodox Reformed (Gereformeerde Kerk vrijgemaakt) congregation in Katwijk, just north of The Hague, where they had lived for three years.

Its pastor, Folkert Rinkema, initially questioned the continuous service at Bethel as a means to protect the Tamrazyans, but “became convinced” after visiting. He told the newspaper he has preached from Psalm 27 (“The Lord is my light and my salvation—whom shall I fear?”), inspired by their plight.

While about 7 in 10 Dutch adults were raised Christian, just 4 in 10 currently identify as Christian, according to a Pew Research Center survey released this year. The religiously unaffiliated (48%) now outnumber active Christians.

Both Wicke and Wolsheimer noted that the scale of ecumenical cooperation over the asylum service and kinderpardon is largely unprecedented among Dutch Christians.

The ongoing service in The Hague echoed efforts at some US churches to offer sanctuary to undocumented immigrants who face deportation under new White House directives.

A man who lived in the basement of a United Methodist Church in Durham, North Carolina, for 11 months was arrested by immigration officers on his way to meet with US Citizenship and Immigration Services last week, The Raleigh News & Observer reported.

Supporters from the church surrounded the van that Samuel Oliver-Bruno was detained in and spent two hours worshiping and praying for the Mexican national’s release. Due to the demonstration, more than two dozen were arrested, including Bruno’s son, who is a US citizen.

According to Church World Service, a ministry supporting displaced people and immigrants, Oliver-Bruno was among more than 50 people, including 11 children, taking sanctuary in US congregations, Religion News Service reported. Christians who favor immigration reform recently vocalized support and prayers for asylum seekers making their way to the US-Mexico border by caravan.

“… We encourage churches—both in the US and in Latin America—to respond with Christ-like love to the vulnerable families and individuals who form this caravan,” wrote members of the Evangelical Immigration Table. “We are very encouraged to know that many churches are already providing care for immigrants in their communities, along with those who may arrive in the future.”

Though the countries offer different contexts for questions over immigration and asylum, author Matthew Kaemingk compares the Netherlands and the United States in his recent book Christian Hospitality and Muslim Immigration in an Age of Fear. The Dutch committed to accepting as many as 7,000 migrants amid the surge of refugees enturing the European Union since 2015.

As CT indicated in its review, “though the situations are hardly identical, the Netherlands remains a relevant comparison point because each nation shares an abiding commitment to some form of political pluralism.”

A generation ago, Dutch Christians in the Netherlands also sacrificed much to save asylum seekers crossing their borders. CT has featured the story of Diet Eman, who took part in the Dutch Underground to save Jews fleeing Nazi forces.