Ronald Reagan understood the power of metaphor. From his stirring election-eve speech in 1980 to his moving farewell address eight years later (and in more than 30 instances in between), the “Great Communicator” challenged the United States to be a model to the world of freedom, justice, and opportunity—a “shining ‘city upon a hill.’” Reagan borrowed the phrase, he told his audiences, from “an early Pilgrim” named John Winthrop, who had employed the metaphor three and a half centuries earlier “to describe the America he imagined.”

As a City on a Hill: The Story of America's Most Famous Lay Sermon

Princeton University Press

368 pages

$17.14

Reagan was wrong. But he was not alone. Winthrop’s reference to “a city upon a hill” was part of a lengthy address titled “A Model of Christian Charity” that was written for a Puritan audience in 1630. While we often think of it today as a landmark document of our early history, the message attracted scant attention at the time and was little remembered for generations. Two centuries would pass before it was first republished in the United States and more than another century before it would gain a wide reading.

When Americans finally discovered Winthrop’s message during the height of the Cold War, they ignored its larger historical context, dismissed the vast majority of the address, and zeroed in on a single passage, which they grossly misinterpreted. In a wonderful new book, As a City on a Hill: The Story of America’s Most Famous Lay Sermon, distinguished intellectual historian Daniel Rodgers recaptures Winthrop’s original meaning and explains why it’s relevant to Americans today.

Under a Microscope

Rodgers begins by recreating the context in which Winthrop crafted his larger message. Anthologies of American history and literature typically reproduce the briefest of excerpts, introducing the passage by saying that “A Model of Christian Charity” was a “sermon” delivered by the governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony to Puritan colonists on board the ship Arbella in route to New England. Rodgers contests even these most basic details.

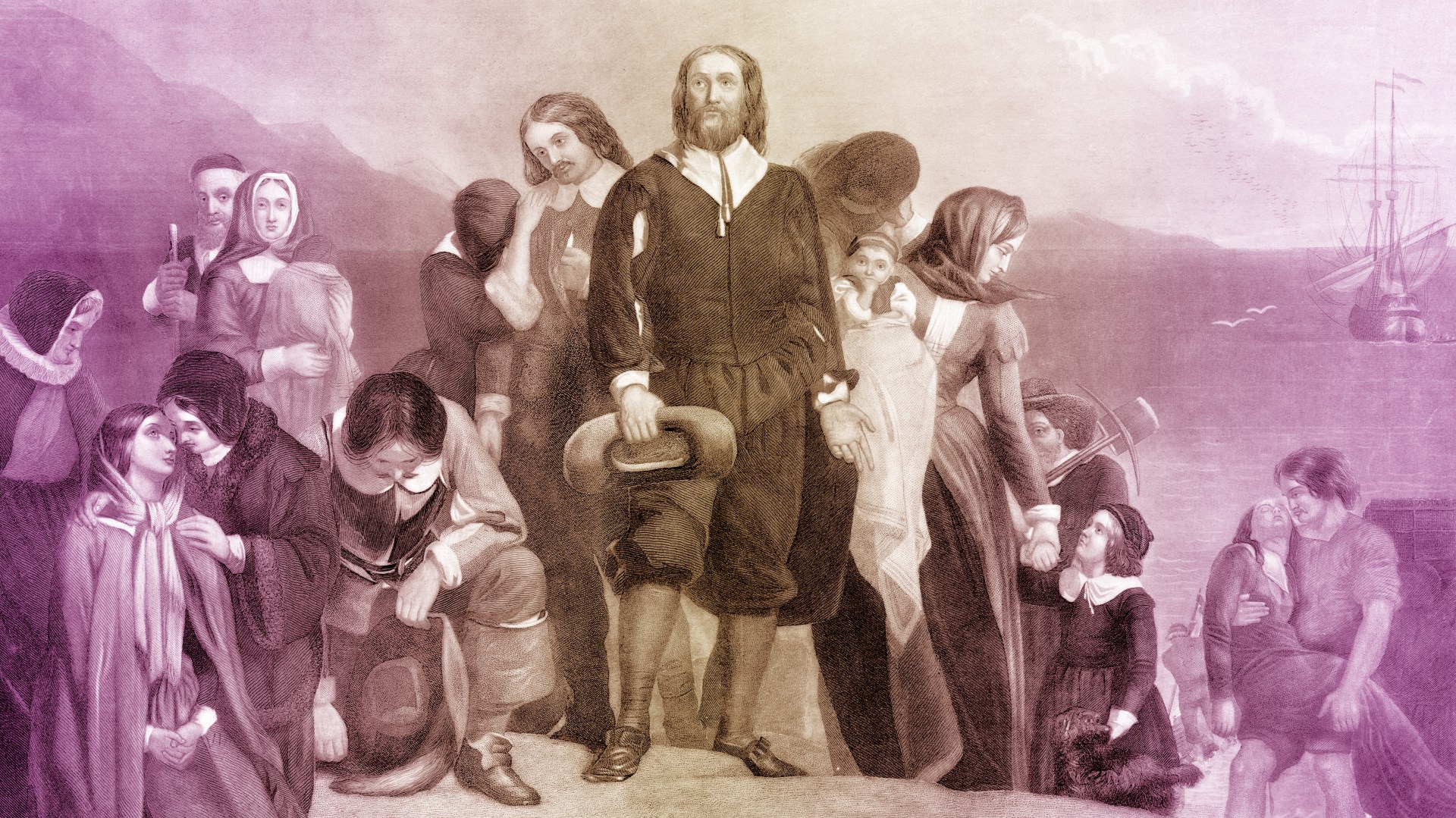

Winthrop never referred to the Model in his shipboard journal, and Rodgers constructs a compelling case that he actually composed it months earlier. It seems likely that he wrote for the Puritans remaining in England (many of whom were helping to finance the expensive venture) as much as for those preparing to cross the Atlantic. If Winthrop actually delivered his address orally on board the ship—and there’s no proof that he did—only a fraction of the Puritan migrants could have heard it in person. The Arbella was one of 16 vessels making up the original Puritan convoy.

Nor was Winthrop’s message literally a “sermon.” Puritan sermons exhibited certain formulaic features missing from the Model, most notably the extended exposition of a biblical text as their starting point and foundation. The “text” that Winthrop expounded is not from the Bible at all, but rather “a seventeenth-century moral truism,” namely that God in his providence has ordained inequality between rich and poor, the powerful and the weak. Rodgers devotes time to these minor details, not because they are hugely significant in themselves, but to alert us that the story has been embellished over the years and to prepare us to revisit afresh an episode from our past that we think we already know.

Toward that end, Rodgers leads the reader through a thorough reading of Winthrop’s entire address. Modern editions of “A Model of Christian Charity” run to 20 or more pages. We remember it for 22 words: “For we must consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill, the eyes of all people are upon us.” Wrenched from the larger document, this solitary sentence becomes the earliest known statement of American exceptionalism, testifying not only to the unique mission of the Puritans but more broadly to that of the future United States. That is how Ronald Reagan read it, as well as almost every president and presidential aspirant since, from Newt Gingrich and Mike Huckabee to Bill Clinton and Barack Obama. Politically inclined Christian writers have done so as well. Bestselling author Eric Metaxas, for example, writes that “we may trace the seed of what we think of as American exceptionalism to the summer of 1630.”

But as Rodgers points out, it’s impossible to read the Model in its entirety and arrive logically at this conclusion. The key word in the title of Winthrop’s address is charity, and the predominant theme in Winthrop’s message is not mission but love. The Puritan leader exhorted his fellow migrants to “love one another with a pure heart,” to “bear one another’s burdens,” to be willing to sacrifice their “superfluities” (material surpluses) “for the supply of others’ necessities.” If they failed in these particulars, the governor warned, they would almost certainly fail in their larger undertaking.

Which brings us to Winthrop’s famous oft-quoted phrase, adapted from the Sermon on the Mount (Matt. 5:14). Far from claiming that the Lord had chosen the Puritan migrants to serve as a shining example to the world, Winthrop was instead reminding them that it would be impossible to hide the outcome if they failed. With 16 ships carrying more than 1,000 passengers, they were embarking on what was, given the technological context of the day, an undertaking of monumental proportions. Their departure would unavoidably attract attention, and many of their non-Puritan countrymen, who resented their criticism of England’s king and his established church, would be hoping to see them stumble. If Winthrop had been writing today, he could have conveyed his point by telling his audience that everything they did would be under a microscope, and the watching world would hope to see them fail.

Winthrop’s point, then, Rodgers explains, was not that the Puritan colony was “destined to be a radiant light to the world but that they would need to work out their ambitions under the world’s most intense, critical scrutiny.” So it is that in the very next sentence after noting that “the eyes of all people are upon us,” Winthrop issued a warning: “If we deal falsely with our God in this work we have undertaken . . . we shall be made a story and a by-word through the world.” What was worse, their failure would “open the mouths of enemies to speak evils of the ways of God.” Rather than puffing up the Puritans with claims of a divine mission, Winthrop intended his allusion to send a chill down their spines. In sum, Winthrop’s reference to a “city upon a hill” was intended more as a warning than an affirmation; it was an exhortation to self-criticism, not self-congratulation.

This element of warning has been wholly lacking from Winthrop’s metaphor as Americans have remembered it since the 1950s. Celebration has drowned out circumspection, a transformation neatly embodied by Reagan’s routine addition of the adjective shining to Winthrop’s metaphor. But does this matter? In 2016, as Rodgers acknowledges, the country elected a president who cares little about American history and who emphasizes America’s “disasters,” not our shining example. Maybe our love affair with the image of a “city upon a hill” is coming to an end.

A Call to Humility and Faithfulness

But even if so—and it’s too soon to tell—there is still much that we can learn from Rodgers’s masterful history of America’s most famous, and most misunderstood, “lay sermon.”

For one thing, it reminds us that historical “revisionists” don’t reside exclusively within the academy. None of us—Christians and non-Christians, political liberals and conservatives—are immune to the very human penchant for creating self-justifying historical narratives that reinforce our sense of identity.

More to the point, the book’s lessons are particularly relevant to American evangelicals. One of the greatest challenges that we have faced over the years has been to work out what it means to be both a Christian and an American citizen. As much as we might wish otherwise, these aspects of our identity are inevitably in tension, and negotiating them faithfully is hard. Unfortunately, one of the most common ways that we have tried to resolve the tension is to make it disappear, and we have accomplished that act of legerdemain, in our own minds, at least, by inventing the myth of a Christian founding.

It can be comforting to tell ourselves that, even a century and a half prior to independence, one of the earliest of our “founders” prophesied that God had chosen the future United States for a special mission to the world. But as Rodgers reminds us, the “we” in Winthrop’s “we shall be as a city upon a hill” was never the future United States or any other human kingdom. The Puritans who joined him in a pilgrimage to a new world came in order to purify and enlarge the church, not to found a new nation or extend an existing empire. If anything, Winthrop’s metaphor cautioned the Christian not to be at home in the world. It testified to an inescapable tension between Christ-followers and the surrounding culture, and it reminded them that even the most devout were prone to stumble. It was a call to humility and faithfulness, not to “destiny and greatness.”

Robert Tracy McKenzie teaches history at Wheaton College. He is the author of The First Thanksgiving: What The Real Story Tells Us About Loving God and Learning from History (IVP Academic) and A Little Book for New Historians: Why and How to Study History (IVP Academic).