“File this, Francie, and make copies of this letter, would you,” I said to my secretary without looking up from my desk. “And,” I sighed, “would you please pull out the sofa bed one more time?”

“Are you serious? Again?”

“Again,” I said. For the fourth time that day, I needed to be lifted out of my wheelchair and laid down. Then I had to undress to readjust my corset. Shallow breathing, sweating, and a skyrocketing blood pressure signaled that something was pinching or bruising my paralyzed body. As my secretary tissued away my tears and unfolded my office sofa bed, I stared vacantly at the ceiling. “I want to quit this,” I mumbled.

Francie shook her head and grinned. As she gathered the pile of letters off my desk and got ready to leave, she paused and leaned against the door. “I bet you can’t wait for heaven. You know, like Paul said, ‘We groan, longing to be clothed instead with our heavenly dwelling’” (2 Cor. 5:2).

My eyes dampened again, but this time they were tears of relief. “Yeah, it’ll be great.”

In that moment, I sat and dreamed what I’ve dreamed of a thousand times: the hope of heaven. I recited 1 Corinthians 15 (“The perishable must clothe itself with the imperishable”), mentally rehearsed a flood of other promises, and fixed the eyes of my heart on future divine fulfillments. That was all I needed. I opened my eyes and said out loud, “Come quickly, Lord Jesus.”

This experience often occurs two or three times a week. Physical affliction and emotional pain are, frankly, part of my daily routine. But these hardships are God’s way of helping me to get my mind on the hereafter. And I don’t mean the hereafter as a death wish, psychological crutch, or escape from reality—I mean it as the true reality.

Looking down on my problems from heaven’s perspective, trials looked extraordinarily different. When viewed from below, my paralysis seems like a huge, impassable wall, but when viewed from above, the wall appears as a thin line, something that can be overcome. It is, I’ve discovered with delight, the bird’s-eye view found in Isaiah 40:31: “Those who hope in the Lord will renew their strength. They will soar on wings like eagles; they will run and not grow weary, they will walk and not be faint.”

Eagles overcome the lower law of gravity by the higher law of flight, and what is true for birds is true for the soul. If you want to see heaven’s horizons, all you need to do is stretch your wings. (Yes, you have wings, and you don’t need larger, better ones; you possess all that you need to gain a heavenly perspective on your trials.) Like the wall that becomes a thin line, you’re able to see the other side.

That’s what happened to me that day in my office. I was able to look beyond my “wall” to see where Jesus was taking me on my spiritual journey.

Scripture presents us with this eternal perspective. I like to call it the “end-of-time view.” This view separates what is transitory from what is lasting. What is transitory, such as physical pain, will not endure, but what is lasting, such as the eternal weight of glory accrued from that pain, will remain forever.

As the apostle Paul writes, “For our light and momentary troubles are achieving for us an eternal glory that far outweighs them all” (2 Cor. 4:17). The apostle Peter, too, writes to Christian friends being flogged and beaten, “In all this you greatly rejoice, though now for a little while you may have had to suffer grief in all kinds of trials” (1 Pet. 1:6).

Rejoice? When you’re being thrown to lions?

This kind of nonchalance about gut-wrenching suffering used to drive me crazy. Stuck in a wheelchair and staring out the window at the fields of our farm, I wondered, Lord, how in the world can you consider my troubles “light and momentary”? I will never walk or run again. I’ve got a leaky leg bag. I smell like urine. My back aches. I’m trapped in front of this window.

Years later, however, the light dawned: The Spirit-inspired writers of the Bible simply had a different perspective, an end-of-time view. Tim Stafford writes, “This is why Scripture can seem at times so blithely and irritatingly out of touch with reality, brushing past huge philosophical problems and personal agony. That is just how life is when you are looking from the end. Perspective changes everything. What seemed so important at the time has no significance at all.”

Mind you, I’m not saying that my paralysis is light in and of itself; it only becomes light in contrast to the far greater weight on the other side of the scale. And although I wouldn’t normally call three decades in a wheelchair “momentary,” it is when you realize that “you are a mist that appears for a little while and then vanishes” (James 4:14).

Nothing more radically altered the way I looked at my suffering than leapfrogging to this end-of-time vantage point. When God sent a broken neck my way, he blew out the lamps in my life that lit up the “here and now” and made it so captivating. The dark despair of total and permanent paralysis that followed wasn’t much fun, but it sure made heaven come alive. And one day, when our Bridegroom comes back—probably when I’m right in the middle of lying down on my office sofa for the umpteenth time—God is going to throw open heaven’s shutters. There’s not a doubt in my mind that I’ll be fantastically more excited and ready for it than if I were on my feet.

In the meantime, suffering hurries my heart homeward.

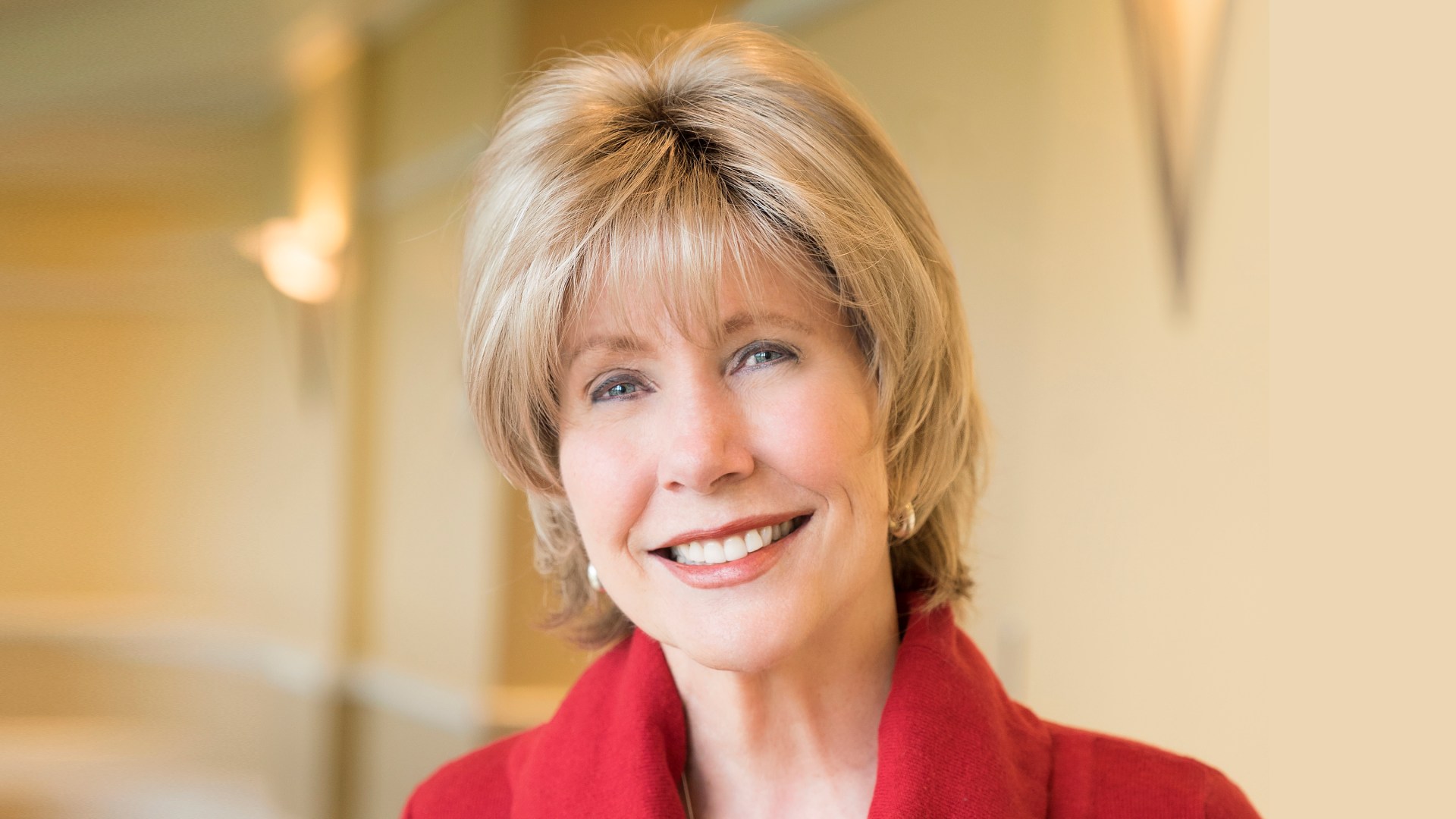

Joni Eareckson Tada is the author of over 50 books, including her best-selling autobiography, Joni. She and her husband, Ken, reside in California.

This essay was adapted from Heaven by Joni Eareckson Tada. Copyright © 2018 by Joni Eareckson Tada. Used by permission of Zondervan. www.zondervan.com.