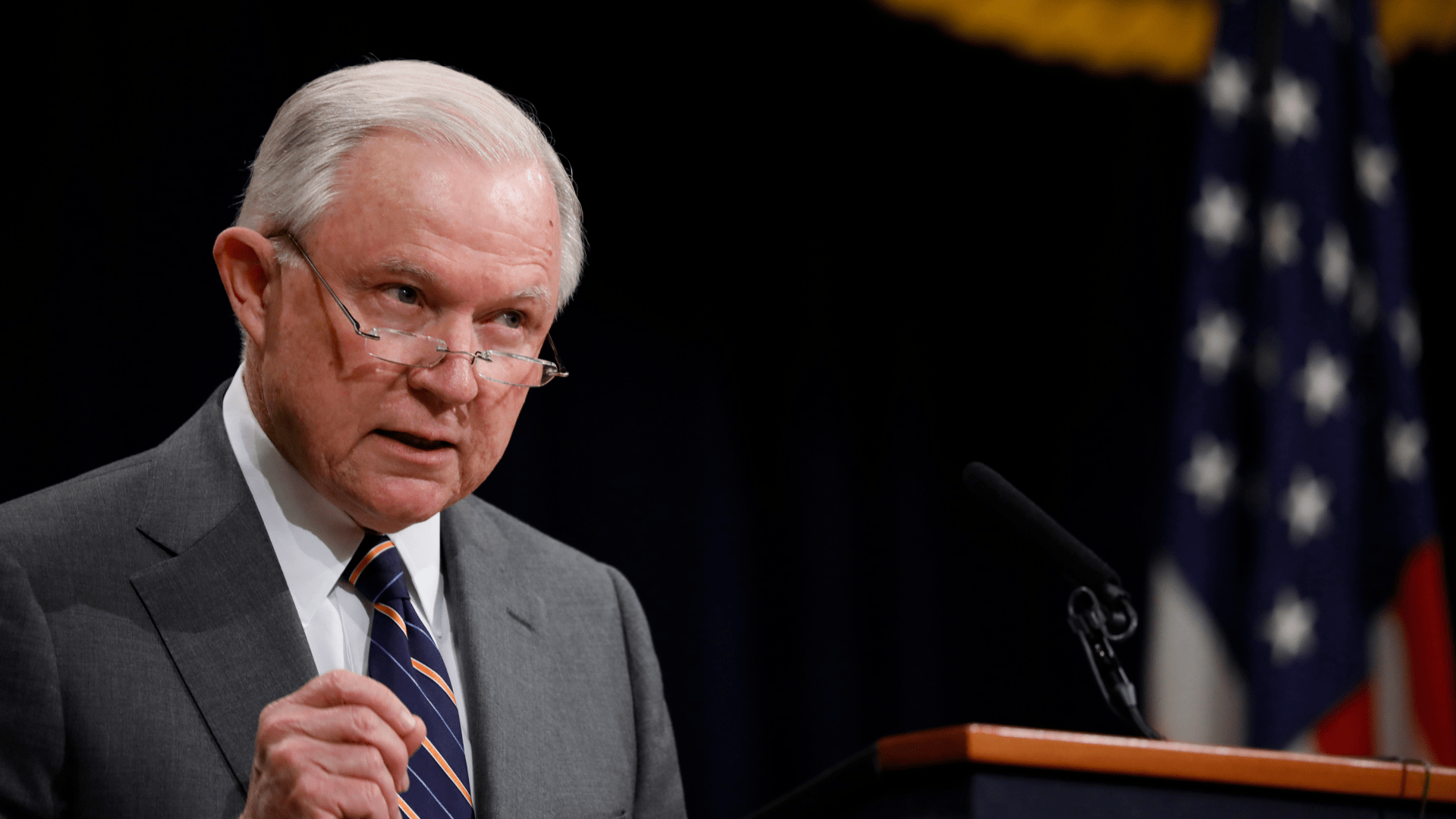

Earlier this week, US Attorney General Jeff Sessions was interrupted by a Methodist minister in a clerical collar who shouted verses from Matthew 25 during a religious liberty event in Boston.

“Brother Jeff, as a fellow United Methodist, I call upon you to repent, to care for those in need, to remember that when you do not care for others, you are wounding the body of Christ,” said Will Green, pastor of of Ballard Vale United Church in Massachusetts.

Green’s remarks, followed by another outcry from a Baptist pastor, led both clergy to be escorted from the event. The Trump cabinet member briefly responded, “Thank you for those remarks and attack, but I would just tell you we do our best every day to fulfill my responsibility to enforce the laws of the United States.”

In a news clip gone viral, Green said to Sessions’s face what some members of the nation’s second-largest Protestant body have articulated in statements, tweets, and casual conversation: They’re unsettled to see a fellow member of the United Methodist Church (UMC) enforcing policies their tradition opposes, specifically, the White House directive to apprehend and separate families crossing the US border.

United Methodist leaders have adopted resolutions in favor of comprehensive immigration reform and declared Sessions’s own zero-tolerance stance as “unnecessarily cruel.” More than 600 clergy and laypeople filed an official complaint against him with the UMC, though it was ultimately dismissed by his district this summer.

“I don't believe there's anything in the Scripture or anything in my theology that says a secular nation state cannot have lawful laws to control immigration,” said the attorney general, the highest-ranking Methodist politician.

The denominational groundswell against Sessions—an Alabama Republican and a member of Ashland Place United Methodist Church in Mobile— continues to raise questions over when and how the church should discipline one of its own.

“We deeply hope for a reconciling process that will help this long-time member of our connection [Sessions] step back from his harmful actions and work to repair the damage he is currently causing to immigrants, particularly children and families,” read a letter from UMC leaders filed July 18.

The complaint, which cited “chargeable offenses” of child abuse, immorality, racial discrimination, and “dissemination of doctrines contrary to the standards of doctrine of the United Methodist Church,” was quashed over the summer by the district superintendent of the Alabama-West Florida UMC Conference, which oversees Sessions’s home church. The justification for dismissing the complaint? Duty-bound politics is not personal.

Backlash upon Backlash

“A political action is not personal conduct when the political officer is carrying out official policy,” read the dismissal, offered in a statement from Bishop David W. Graves, resident bishop of the Alabama-West Florida Conference, who concurred with the decision.

According to the dismissal notice, Sessions simply carried out the official program of the president and the Department of Justice, so his behavior didn’t constitute an “individual act” and therefore was not covered under the UMC’s Book of Discipline.

His Methodist critics have not been so willing to separate the two, going on to push back against Sessions’s appeal to the Bible—the oft-cited, oft-ignored opening of Romans 13—to defend the policy.

“While I could fully understand the informal complaints about Sessions, and though I didn’t expect much success for the formal complaint…I don’t understand the rationale for the dismissal of the complaint,” said Will Willimon, a Methodist theologian, UMC bishop, and Duke Divinity School professor, in a response to CT.

“‘Political actions are not personal conduct’? What’s that supposed to mean? What’s the basis in Scripture for that statement? I know nothing in our Book of Discipline that bifurcates personal behavior from public, politically motivated behavior. Whatever happened to, ‘We must obey God rather than human beings (Acts 5:29)?”

William B. Lawrence, a former president of the UMC’s judicial council, called the reasoning behind the dismissal “problematic.” “I do not follow the logic that grants someone, even the president of the United States, the right to ‘superior orders’ with regard to church law,” he stated to the Religion News Service.

Still, such complaints are rare, and laity usually meet with their pastor or district superintendent to resolve, he said in a United Methodist News Service article.

Essentially, there is no precedent for the denomination disciplining lay members in a situation like Sessions’s, and perhaps no need.

“No Methodist to my knowledge in history has been ecclesially punished for political views or actions,” Mark Tooley, a Methodist and the president of the Institute of Religion and Democracy, told CT. “Church members were sometimes disciplined for owning slaves, which Methodism opposed. But Methodist laity weren’t punished for politically supporting slavery or, if in government, for upholding it.”

“Should they have been? Should members of any church be punished and potentially excommunicated for participating in political or state acts violating church teaching? What church does so?” said Tooley, who supported the dismissal, but disagreed with the rationale. “Some Catholics argue the Eucharist should be withheld from pro-abortion rights Catholic lawmakers, but it almost never happens.”

Tooley pointed out that, though a historically liberal denomination, United Methodism maintains conservative stances against same-sex marriage and abortion in certain cases, and members of his denomination have not been proactive in filing charges against liberal politicians whose positions oppose those.

Methodists are the second most popular Protestant denomination in Congress, with 17 Democrats (7%) and 27 Republicans (9.2%), and politicians Hillary Clinton and George W. Bush are both Methodists.

What Place for Discipline?

The majority of Protestant senior pastors in the United States (55%) were not aware of members in their churches ever being formally disciplined, according to an April survey from LifeWay Research. Only 16 percent said their church had disciplined a member within the past year.

Of all denominations surveyed, Methodists were the least likely to say a church member had been disciplined in the previous year (4%). By contrast, 29 percent of Pentecostal pastors, 19 percent of Baptist pastors, and 9 percent of Reformed/Presbyterian pastors said the same.

When asked about the responsibility to administer church discipline, responses varied as to who should take the lead. Few said the responsibility belongs solely to the church elders (14%), the pastor (9%), trustees or board members (4%), or deacons (1%).

Just over half (51%) said two or more of these groups must come to an agreement for discipline to be enacted, and 18 percent said there was no formal discipline process at their churches. Mainline pastors (24%) were more likely to say there was no formal discipline policy than their evangelical counterparts (15%).

Methodists like Sessions are, according to LifeWay’s findings, the least likely to see church leaders administer discipline to its members. Regarding their own churches, 85 percent of Methodist senior pastors agreed with the statement, “A member has not been formally disciplined since I came as pastor nor prior as far as I know.” Methodist pastors are also the most likely to say they have no official policies in place for disciplining church members (37%).

The denomination does, however, have its Book of Discipline, which explicitly permits church trials and even the expulsion of members, though “pastoral steps” like a conversation between the charged member and the member’s pastor and district superintendent would be the first step.

“I hope [Sessions’] pastor can have a good conversation with him and come to a good resolution that helps him reclaim his values that many of us feel he’s violated as a Methodist,” regional conference elder David Wright told UM News, adding, “I would look upon his being taken out of the denomination or leaving as a tragedy. That’s not what I would want from this.”

Over the summer, a Justice Department spokesperson said Sessions would not comment on the matter, and representatives of the Alabama-West Florida Conference also declined to comment.

“It’s not immoral, not indecent, and not unkind to state what your laws are and then set about to enforce them, in my view,” Sessions said on Monday. “I feel like that’s my responsibility and that’s what I intend to do.”