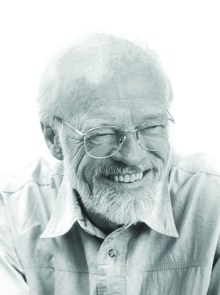

Eugene Peterson—who died in October at age 85—is best known, perhaps, as the author of The Message, his vernacular paraphrase of the Bible. But for many pastors and church leaders, Peterson was also a mentor who taught them to be shepherds rather than CEOs—in large part by modeling that approach himself. Drew Dyck, acquisitions editor at Moody Publishers, spoke with Peterson in 2017 as one of his final books (As Kingfishers Catch Fire) was published. They spoke about recent developments across the ministry landscape, the seriousness of the pastoral calling, and how The Message sprouted from his desire to truly know and listen to the people in his ministry. Pieces of that interview appear here for the first time.

As Kingfishers Catch Fire: A Conversation on the Ways of God Formed by the Words of God

Waterbrook

400 pages

$20.31

In the preface of As Kingfishers Catch Fire, you write that the Christian life is “the lifelong practice of tending to the details of congruence.” What does that look like in a pastor’s life?

As pastors we’re interested in getting people to live a life that is congruent with the gospel. One of the things I realized from day one is that I needed to listen to congregants and not just put things into their heads. This is one of the wonderful things about being a pastor. You get the time and the opportunity to make connections with the everyday lives of people in your congregation. You can’t just treat Christianity as a pile of ideas from which to add and subtract.

You grew up in farming country, and your father was a butcher. Did that environment shape you as a pastor?

By all means. People who work with the soil and with animals learn to respect what they’re doing and the subjects of their work. My dad had one man working for him who he would send to the farms or ranches. In the store, we called him “the killer,” because that’s what he did. He was the one who got them down. But he was so respectful of the animals. He might have been a killer, but he was not a murderer. That soaked into me, and by the time I got out of college, I’d absorbed something important about the Christian faith and its understanding of creation.

If you were training as a young pastor today, in what context would you be looking to minister?

It would be local, relational. If you’re content to stay with one congregation for a while, you could have a congregation of four, five, six hundred, and still know everyone. I had a congregation of 600, and I knew everybody’s name.

I don’t think you can help anyone live a congruent life without knowing their name. How can you be personally involved in someone’s life and not know who their children are, who their spouses are, or the trials they go through every day? It just doesn’t work.

When I was at Seattle Pacific College, we had a student body of about 500. As student-body president, I determined to learn the name of every person on that campus. And I did. I didn’t like the pastors who didn’t know my name. “Hey, you,” they would say and never bother to get acquainted.

I remember one of my teachers in the English department. I was writing a column for the student newspaper, and I began with a careless reference to the poet Chaucer. My professor called me in and said, “Eugene, have you ever read Chaucer?” I said, “No.” And she pulled a book off the shelf, put it in my hand, and said, “You start reading this and don’t come back until you’ve finished it.” Well, I had no idea that Chaucer was such an interesting person!

That stuck with me. Don’t think you understand someone just because you know about them.

As you know, community has become something of a buzzword in the church today, yet in some ways we have less of it even though we talk about it more. Why is that?

Probably because many people in churches today don’t have a sense of community, and in order to get a sense of community, church leaders start gathering people up and giving them jobs. We’ve lost a talent for relationship and showing interest in the other person. We don’t have community because we skip over the critical part: being in relationship with the people, knowing their kids, knowing their jobs, knowing the neighborhood.

When I was starting up for my first church, we met in the basement of our home because we couldn’t afford anything else. There was a low ceiling, cement walls. And one of the high school girls who was worshiping with us came out one day and said, “Oh pastor, I love coming here. I feel just like one of those early Christians in the catacombs.” Pretty soon all the young people in the church were calling it Catacombs Presbyterian Church. I liked that.

Pastoral ministry is a weighty call. How can pastors stay lighthearted in the midst of it?

I’m not sure you can stay lighthearted. Being lighthearted doesn’t mean you’re oblivious to or innocent of the difficulties in a person’s life. Sometimes being lighthearted means not taking somebody seriously.

What have you said “no” to consistently?

I suppose anything that verges on the superficial. I had a friend in my first parish whose strategy was to take all the kids in the neighborhood to football games. But he didn’t know any of these kids. He didn’t know their names. That struck me as odd. There’s a lot more opportunity in taking people to see a football game than just getting them out there to see it.

We live in a time when people are very skeptical of religion. They may even see it as dangerous. In that context, how can church leaders wield any sort of spiritual authority in a way that is faithful and credible?

You have to start small. Invite people over for a meal, and just keep at it. People in our culture tend to be a little suspicious of anybody who takes interest in them. What are they trying to get out of me? We’re trying to find quick solutions for something that takes a lot of time. We’ve dug ourselves into a hole, and we’ve got to start filling the hole by forming relationships with our neighbors.

When I was in Baltimore in the 1980s, there were riots and murders. Things were a mess, and some members of my congregation started buying guns. I have nothing against guns, but in that context, it didn’t seem very smart. So I started to preach on Galatians, Paul’s angriest letter. And I told my congregation, “Look, Jesus wants you to be free of this kind of stuff.” But they didn’t pay much attention.

After a few weeks, I started a Bible study for men. I wanted to teach them Galatians so they could understand freedom in Christ. I always got there early and made a pot of coffee. And during the study, they just sat there stirring sugar into their coffee.

I went home and told my wife, “I think I’ll teach them Greek. If they can learn Greek, they’d really get it.” And she said, “Yeah, that would really empty the place out fast.” So instead I translated—if you want to call it that—the text into the American vernacular. I’d been with these people for several years, and I knew how they talked and what they talked about. After using this approach for a couple of weeks, I would come back to clean up afterwards, and all the cups were full of cold coffee. No one had drank their coffee. So I just kept doing that, and much of it ended up in The Message.

Did this interview resonate with you? Let us know here.