When I was young, my mother made a wreath that was composed of natural materials—pinecones, needles, thistles—gathered from places where we had taken family vacations. Setting aside distinctions between art and craft, it has always been evident to me that the wreath possessed certain artistic qualities: an expression of her creative abilities, an intentional work with aesthetic appeal. What became equally evident to me over time was that the wreath functioned in another way.

Marissa Voytenko

Marissa VoytenkoHanging on the wall in my parents’ living room as it has for decades now, it acts as a witness to and a reminder of our shared time as a family. Whenever I see it, I feel my feet walking on trails in the early morning, I hear the sound of metal tent stakes being hammered into the ground, I taste roasted marshmallows, and I see the faces of family members, some now gone.

Bryn Gillette

Bryn GilletteLike other works of memorial art, the “memory wreath,” as my mother termed it, serves a purpose beyond mere decoration. It shapes our family’s collective memory as well as my individual memory. At a much broader level, the same could be said for the shaping of social memory through the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, the National September 11 Memorial, the public murals in Belfast, Northern Ireland, or the new National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama.

More controversially, this calls to mind the heated—at times even violent—ongoing debate in America over whether Confederate monuments should be taken down. One fascinating byproduct of this national discourse is the recognition that regardless of whether one believes that these statues represent a cultural identity that should be preserved or a history of racism and oppression that must be removed, we all seem to agree that these works of art are functioning in some meaningful way.

They are, in short, doing something.

Christian philosopher Nicholas Wolterstorff points out that memorial art serves an important social function by helping us remember people and events from our past that have shaped our contemporary collective identity.

This is just one aspect of Wolterstorff’s larger argument that art is not just for passive contemplation, something simply to be looked at in a museum and then left behind. In his influential book Art in Action, he claims that “works of art are instruments and objects of action.” The art that humans make can be—and always has been—used in a wide range of social contexts: from religious rituals to our places of work, from birthday parties to high school dances.

The shaping of our public memory, then, is just one of the many meaningful and practical ways that art functions in our communal and individual lives. If the arts have such power to start conversations, bring communities together, and even tear communities apart, should Christians employ them as a tool for evangelism?

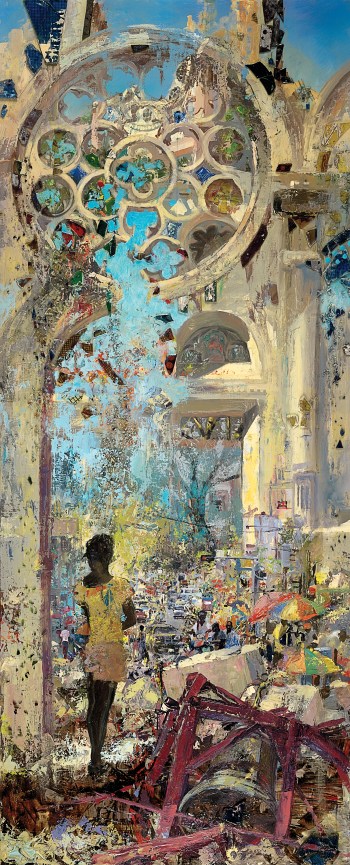

Michelle Arnold Paine

Michelle Arnold PaineReasons for Caution, Reasons for Optimism

One concern about employing the arts in evangelism is that it could corrupt art by requiring pedagogical content and purpose at odds with authentic artistic expression. As Byron Spradlin, president of Artists in Christian Testimony International, explains, “Our inclination so often is to believe that using the arts in evangelism will compromise both art and an artist’s integrity.”

Similarly, concerns might be raised that if the art employed in evangelism does not make explicit reference to Jesus Christ and the salvation that is offered through his life, death, and resurrection, then the gospel message loses its significance. We are presented with what seems to be a lose-lose situation.

However, there are reasons for optimism—and action. For many people, the arts have been a way to experience God and to come to know the truth of God’s revelation in Christ. For example, Henry Lucey-Lee, national director of Arts Ministry for InterVarsity Christian Fellowship, argues that, when it comes to evangelism, college students today “will respond to quality art that conveys the beauty of God.”

“We still need Scripture and good theology,” he adds. “But art is often the first step college students today will take as they open themselves to Jesus.”

If that is the case, then the question becomes not should we use the arts in our evangelism but how should we? And what provides guidance for doing so responsibly, faithfully, and creatively?

An Unexpected Old Testament Evangelist

The biblical figure Bezalel, unknown to most Christians but beloved by Christian artists, may point the way. At Mount Sinai, with the Ten Commandments, God gave Moses specific instructions about making the tabernacle. Thankfully, God also provided the artistic gifts required to craft a place worthy of the divine presence. In Exodus 31, God filled Bezalel with the Holy Spirit, blessed him with artistic skills, and called him to the task of building the tabernacle.

In Bezalel, Scripture provides us with a model not only for faithful engagement with the arts but also for the responsible use of the arts in our evangelism. That might seem at odds with what Bezalel was actually doing, making a place for the presence of God in the midst of God’s chosen people. But his story embodies several principles that can serve as the building blocks of a biblical and theological understanding of art that can guide its evangelistic potential.

Jason Leith

Jason LeithThe Arts as a Calling

Like Moses, Bezalel was given a particular calling. God set him apart for a task—significantly, called him by name—to serve and glorify God in a particular way (v. 2). Being an artist was how Bezalel lived out his life before God. Unfortunately, the legitimacy of an artistic calling has often been questioned within the church. Bezalel’s calling forces us to reckon with the arts as a way to honor God and fulfill one’s vocational task.

Thankfully, strides have been made in this regard (e.g., church galleries, arts ministries, artists in residence), but artists often still feel isolated, unwelcome, or even betrayed by the church. Yet the artistic vocation is as legitimate a calling as any other, and it should be recognized and affirmed by the church as a way to serve the body of believers.

The Arts as a Gift

Bezalel did not gain his expertise in the arts on his own. The text is clear that Bezalel’s artistic skills are a gift given by God (v. 3). He is utterly dependent on the presence, power, and grace of God, and he is literally inspired—filled with the Holy Spirit—as he receives this gift. Even John Calvin, not typically regarded as a friend of the arts, acknowledged in his Institutes that the arts are “gifts of God.” Like all good things, they are given for God’s glory and our benefit.

Moreover, this gift involves working with given material. Whatever their artistic medium, artists work with the given: paint, clay, wood, language, vocal cords, time. We do not create ex nihilo like God. Our making is, at best, a Spirit-led reordering of given material. The very exercise of this gift, then, is further evidence of our dependence on God and the nature of the arts as a gift.

The Arts as Communal

The popular image of an artist is a lone recluse, toiling in (possibly self-imposed) exile. But with Bezalel, Exodus presents a different image. Oholiab, who comes from a different tribe, joins Bezalel in the task of building the tabernacle (v. 6). Even for those artists who work alone, the arts are not a solitary endeavor; they are a communal activity. Some artistic media (e.g., film and theater) exemplify this particularly well, but all art is ultimately communal. An artist makes something to be viewed, listened to, read, enjoyed.

The communal nature of the arts parallels the communal dynamics of the Christian faith, according to which the triune God, who exists in perfect and eternal fellowship, brings sinful humanity into relationship with the holy and loving God. Indeed, the whole of salvation history fulfilled in Christ might be described as an exercise in eternal community building.

As in any community, when it comes to the arts, we need to be mindful of our responsibilities to others. The church should be willing to be stirred by artists, who might encourage the body of Christ to grapple with challenging art, not simply art they find familiar or aesthetically appealing. Artists, in turn, should consider how their particular artistic calling might best serve the church and align with its mission. Will a new, difficult song appropriately expand a congregation’s musical range, or will it only highlight the worship leader’s abilities?

The Arts as Command

After spending several chapters in Exodus describing what is to be built, God then called, gifted, and commanded people to do that work. The arts are not optional here; they are commanded by God (vv. 6, 11). Making art may not quite be an 11th commandment, but this isn’t the only time God commands artistic activity. Consider Moses making the bronze serpent, the building of the Temple, or the rebuilding of the walls of Jerusalem.

But does the fact that God commissioned art in Scripture necessarily mean that art is required in our communal worship today? Karl Barth found art a “visual aid” to his theological work, but declared that images “have no place at all in a building designed for Protestant worship.”

However, in Exodus 31, we see that the tabernacle—and later the Temple—stood at the heart of the worshiping life of the Israelite people. In the middle of their worship experience was an artistic object, not to be worshiped itself, but to enable and aid their worship of God. Christians in a variety of ecclesial traditions have been blessed and guided in their worship by the presence of the arts in their liturgical context—from the icons of the Eastern Orthodox church to the range of music, dance, and drama in Christian worship around the globe.

Of course, the fact that the arts are commanded by God does not mean that we fulfill that command perfectly. In the biblical narrative, the paradigmatic misuse of the arts—the notorious golden calf incident—is found in Exodus 32, merely one chapter after the text about Bezalel, when Aaron misappropriates these God-given skills to make a golden calf, declaring, “These are your gods, O Israel, who brought you up out of the land of Egypt!” But even when our use of the arts does not approach such blatant idolatry, our artistic faithfulness is still inconstant. Like the rest of creation, even our best artistic expressions exist in a fallen world and await redemption.

The Arts as Evangelism?

What does all of this tell us about the use of the arts in our evangelism?

Bezalel does not fit the typical model of an evangelist. He was not preaching the truth of God to the nations or publishing tracts to be handed out. And yet, as he faithfully fulfilled his calling as an artist, his work had an evangelistic function. Through the creative exercise of his God-given artistic gifts, he bore witness to God.

Of course, Bezalel’s work—like any artwork—was tied to a specific context: He provided a place for God to “tabernacle” among the Israelite people and for this particular people to worship their God. But it is also a model for the ways in which we can bear witness to God, who “tabernacled” on the earth in the Word made flesh (John 1:14). Indeed, for many Christians, the incarnation of Christ not only affirms the goodness of the material world, but it also validates our engagement with and application of the arts.

Cherith Lundin

Cherith LundinOur notion of what evangelism is should not be limited to preaching on the street corner, writing pamphlets, and debating the finer points of theology. Our evangelism should be characterized by our faithful witness to the goodness and grace of God in all aspects of our lives. That witness extends to and includes the calling and work of artists.

Marissa Voytenko, a Chicago-based artist and member of Christians in the Visual Arts, affirms that, for some, the arts can be a more effective way to engage conversations about faith: “As a painter, it’s easier for me to talk about redemption, equality, beauty, and the love of God through my artwork rather than turning directly to Scripture, though it is obviously informed by that. Art can be less threatening to nonbelievers because it allows a broader conversation to happen. It leaves space for multiple perspectives, interpretations, and conclusions. My vulnerability in sharing my work shows risk, and I think it allows for others to be vulnerable as well.”

The faithful exercise of artistic gifts by Christians neither negates the integrity of their art nor threatens the truth of the gospel message, whether the work in question explicitly references Jesus Christ or not. The work of Christian artists is enhanced when they view it as part of their fulfillment of their vocational calling. Similarly, the church’s evangelism is enhanced by the presence of artists, whose witness may provide an encounter with God for people who are unlikely to listen to a sermon, pick up a pamphlet, or read this article.

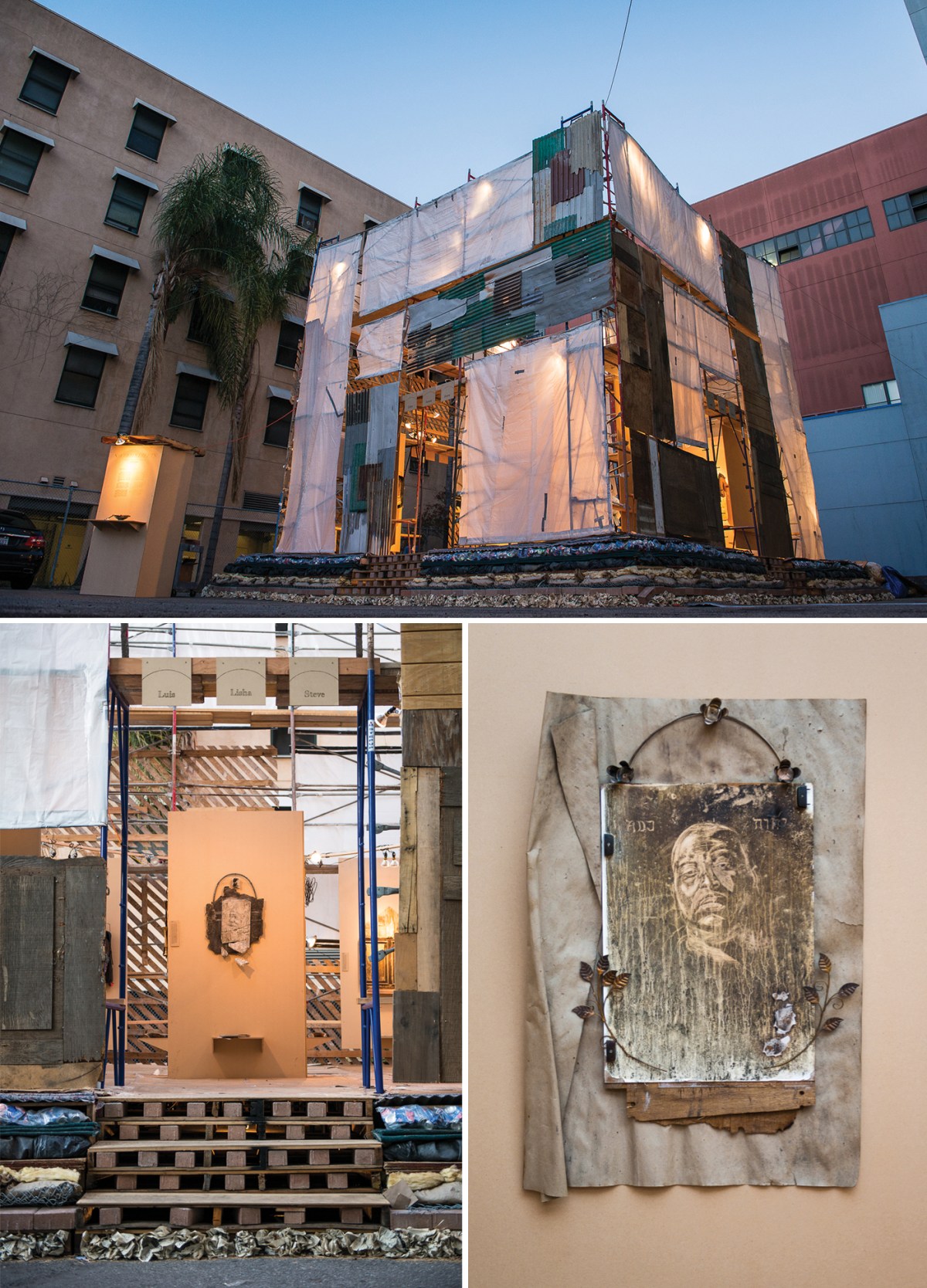

Delro Rosco

Delro RoscoAs Spradlin notes, “The best way for the church to embrace the evangelistic potential of artistic expression is to see artists for what the Bible reveals them to be: people who are unusually wise at imaginative design or expression.” By glorifying God and serving as witnesses to Christ, artists contribute to the church’s evangelistic mission. Here, as elsewhere, art is capable of doing something—something meaningful, practical, and perhaps eternally significant.

Bezalel is rightly remembered as an artist. But his calling—and that of every Christian artist—includes the witness of an evangelist.

David McNutt holds a PhD from the University of Cambridge and is an associate editor at IVP Academic, a guest professor at Wheaton College, and an ordained teaching elder in the Presbyterian Church (USA).

Was this article helpful? Did we miss something? Let us know here.