In this series

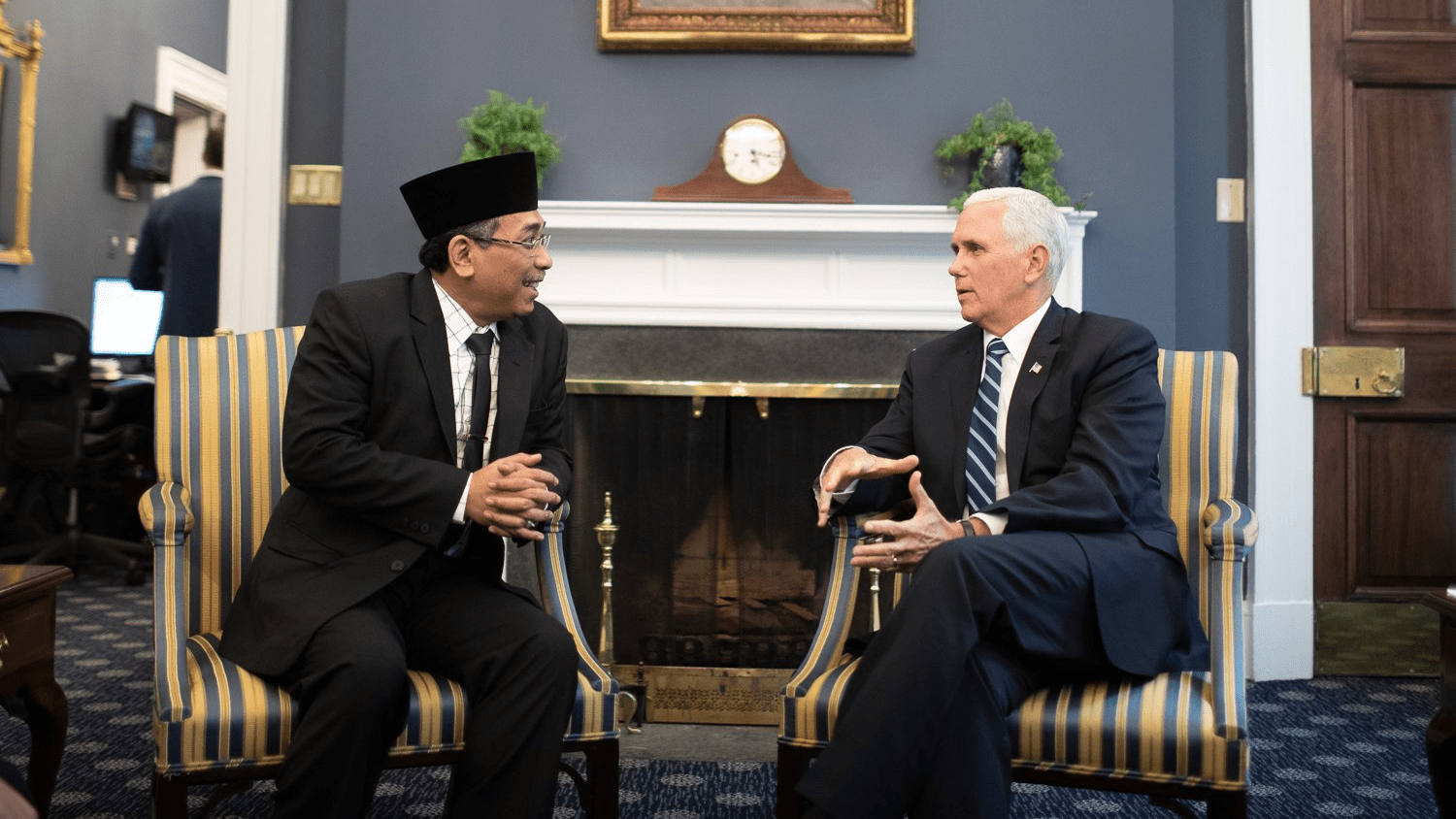

Less than a week after the first family of suicide bombers killed or injured dozens of worshipers at Sunday services in Indonesia, the country’s top Muslim leader met with Vice President Mike Pence to discuss religious freedom in the face of mounting extremism.

“Honored to welcome the @NahdlatulUlama Secretary General to the @WhiteHouse today,” Pence tweeted after his meeting Thursday with Yahya Cholil Staquf, who leads Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), the largest Muslim organization in the world.

“Their efforts opposing radical Islam are critical in Indonesia—where we saw despicable attacks on Christians. @POTUS Trump’s admin stands with NU in its fight for religious freedom & against jihad.”

Last Sunday, a family of six—including four children—believed to be affiliated with the terrorist group Jamaah Ansharut Daulah (JAD) set off explosives at three churches in Surabaya, the second-largest city in Indonesia.

As the holiday of Ramadan began, Staquf sat down with Pence and senior advisers in the West Wing to discuss the attack, which has heightened ongoing concerns from Christians and Muslims alike over radicalization and sectarian violence.

His organization—a Sunni group with as many as 50 million members—has been championed as a model of “moderate Islam” due to its vocal stance against extremism and its efforts to build healthier relationships across faiths. In 2016, CT reported how NU called for majority-Muslim countries to do more to protect freedoms for Christians and other faiths.

One of the victims of Sunday’s attacks was a Christian trained by NU as a church guard; he died blocking a suicide bomber on a motorcycle.

“The VP conveyed deeply personal condolences on behalf of the United States for the events of last weekend, reiterated the administration’s commitment to helping Indonesia and the NU in its efforts to combat extremism, and offered Ramadan greetings to the NU community,” said Johnnie Moore, an evangelical adviser to the Trump administration who also attended.

Thursday’s meeting builds on Pence’s trip to Indonesia last year, when he met Staquf for the first time and praised the nation’s religious tolerance, saying: “As the largest majority Muslim country, Indonesia’s tradition of modern Islam, frankly, is the inspiration to the world.”

Yet the fringe of radical Muslims in Indonesia is gaining clout, raising the risk of violent attacks and increasing Christian persecution in the political sphere. Last year, religious freedom groups began to question the country’s reputation as a religiously tolerant democracy once its top Christian politician, the governor of the capital city of Jakarta, faced protests from hardline Islamists and ended up convicted of blasphemy.

The surprising verdict came as four senior Indonesian political leaders—three Muslims, one Christian—were finishing a US tour seeking partners to promote and preserve the archipelago’s pluralism.

“With the news of Ahok’s sentencing to two years in prison, a pall fell over our gathering,” wrote Paul Marshall, a professor of religious freedom at Baylor University and a scholar with the Leimena Institute, a Christian think tank in Jakarta. “Our very well-informed companions believed this victory for radicalism might be a prelude to the demise of democracy in Indonesia, the world’s largest Muslim-majority country.” (Though he explained for CT why he still has hope.)

That incident, along with other political discrimination targeting Christians and fellow minorities, earned Indonesia a place among “Tier 2” countries for religious freedom violations, as designated by the US Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF).

(Recently, a few prominent evangelical leaders were appointed to the commission: Moore, who was tapped by the Trump administration for the role, as well as Family Research Council president Tony Perkins and founder Gary Bauer.)

In USCIRF’s annual report released last month, the independent agency (which makes policy recommendations to the US State Department) suggested the American government train Indonesian officials in counterterrorism so they might better address violence against places of worship, as well as help fund counter-extremism programs.

As Marshall explained:

If the third-largest democracy on the planet succumbs to Islamic radicalism, then the future of the Muslim world and the rest of us looks dire. The major center of Muslim moderation—and the major counter to ISIS and similar ideologies—will be undercut. This will affect us all.

Staquf has been vocal about what he sees as a necessary responsibility for Muslims to identify elements within their own traditions and communities that make them prone to radicalization and violence.

“Western politicians should stop pretending that extremism and terrorism have nothing to do with Islam,” he told TIME last September. “There is a clear relationship between fundamentalism, terrorism, and the basic assumptions of Islamic orthodoxy. So long as we lack consensus regarding this matter, we cannot gain victory over fundamentalist violence within Islam.”