In this series

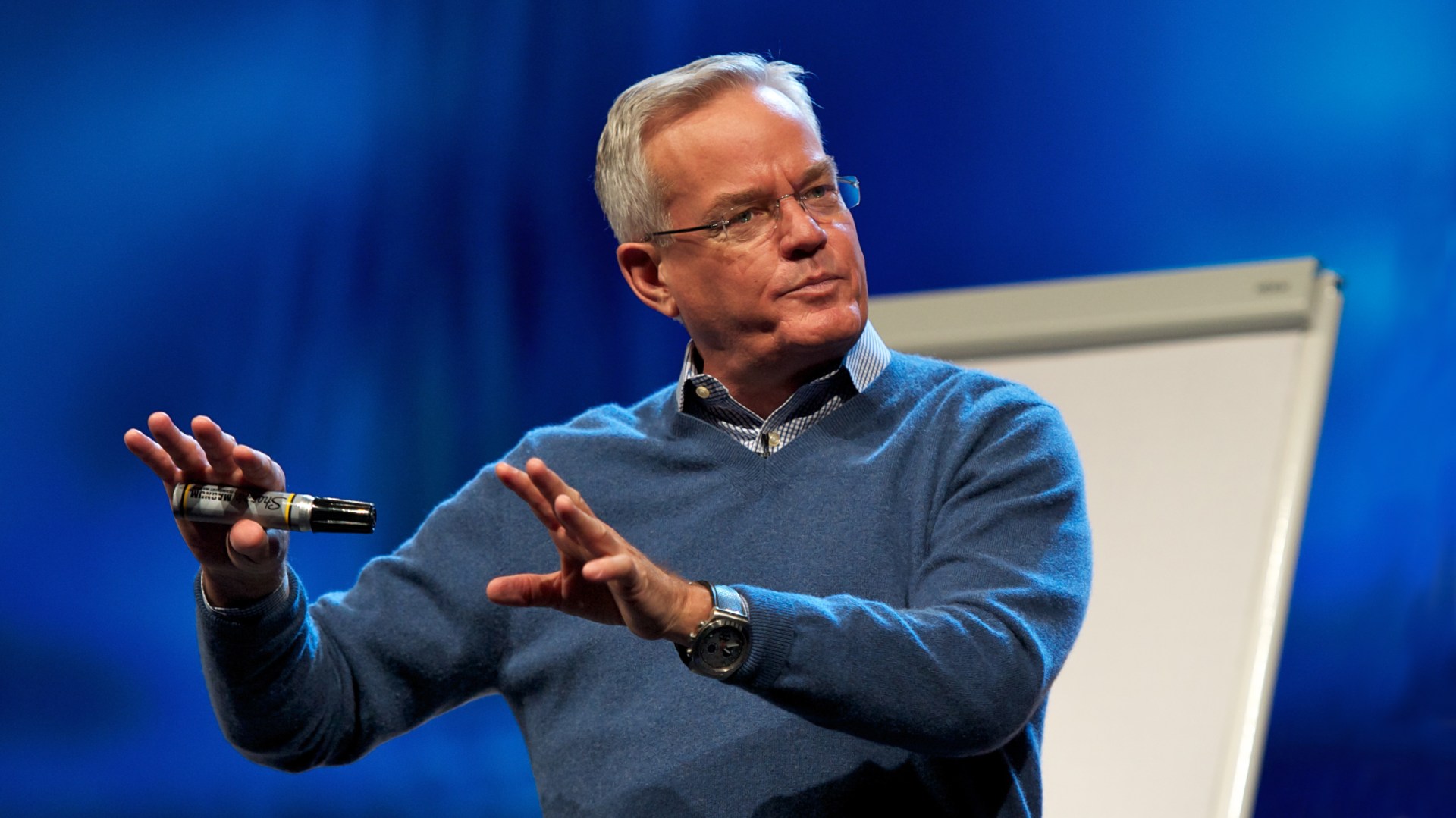

Bill Hybels has stepped down as senior pastor of Willow Creek Community Church, the Chicago-area megachurch he founded over 40 years ago, citing the controversy over recent allegations against him.

Many in the wider Christian community have been confused by those allegations, he said, and the controversy has distracted his church’s leaders from their mission and has hurt the church’s ministries. “They can’t flourish to their fullest potential when the valuable time of our leaders is divided.”

Hybels, who previously planned to retire in October, revealed the news Tuesday evening at a “family meeting” where about 1,000 Willow Creek members gathered at the multisite church’s flagship South Barrington, Illinois, campus.

The crowd listened in silence as their longtime pastor began to read a 12-minute-long prepared statement, then groaned in disappointment when he confirmed what so many of them had feared. Several voices shouted, “No!” across the 7,000-seat auditorium.

Hybels will also leave the board of the Willow Creek Association (WCA), a network of thousands of churches around the world, and will no longer host Willow Creek’s Global Leadership Summit (GLS) in August. “This too was my decision and mine alone,” he said.

Hybels has strongly denied the pattern of misconduct that former Willow Creek staff members recounted in an investigation published three weeks ago by the Chicago Tribune and covered by Christianity Today. At the family meeting, he repeated his denial.

“I’ve been accused of many things I simply did not do,” he said. “But let me acknowledge things I have done. I confess to anger at the accusations. … I sincerely wish my initial response had been listening and humble reflection. I apologize to you, my church, for a response that was defensive instead of inviting learning.”

In last month’s Tribune article, Hybels called the accusations “flat-out lies” and accused a group of former colleagues—including two prominent former staff pastors—of colluding against him to ruin his reputation.

On Tuesday, he told the audience that “I realize now that in certain settings and circumstances in the past I communicated things that were perceived in ways I did not intend, at times making people feel uncomfortable. I was blind to this dynamic for far too long. For that I’m very sorry.”

“I placed myself in situations that would have been far wiser to avoid,” he said. “I was naive about the dynamics those situations created. I’m sorry for the lack of wisdom on my part. I commit to never putting myself in similar situations again.”

Hybels said he would withdraw to consult with counselors and reflect on what God is teaching him. “I have taken these allegations seriously, as have our church elders,” he said. “Some have been misleading, and some have been false. But I have been sobered by these allegations and I am inviting counsel … to help me sort through these in the days ahead.”

After the period of reflection, Hybels plans to return to the church as a member of the congregation.

“Willow will always be my church home,” he said, departing to a standing ovation.

“We accept and see the wisdom in this decision,” said Pam Orr, chair of Willow Creek’s elder board. She said that the church’s work will continue without its founder.

“We will not give up doing the work he called us to,” she said.

Willow Creek members knew big news was coming when the church called the midweek gathering just a day in advance. Some held out hope that Hybels had been able to reconcile with those bringing accusations against him, or even that evidence had been found to disprove the claims. But most saw the resignation coming.

CT

CTAs Steve Carter, the church’s new teaching pastor, prayed over the Hybels family and the church’s elders at the end of the gathering, more in the crowd—arms extended to the stage—began to cry.

Donna Simale, who has been a member of Willow Creek since 1986, couldn’t hold back tears as she described the evening. “I knew” that Hybels would step down, she said. “I just feel so brokenhearted.”

When the news broke last month, “I believed him, and I also knew the people coming forward with concerns,” said Simale. “I felt in my heart there was a misunderstanding.”

Former leaders have accused the church of failing to adequately address several allegations against Hybels, including inappropriate comments, private meetings with female staffers in his hotel room and at his home, intrusive hugs, and, in one case, an unwanted kiss.

Among those raising concerns were Nancy Beach, the first female teaching pastor at Willow Creek; Betty Schmidt, the longest-serving lay elder in the church; John and Nancy Ortberg, former teaching pastors at Willow Creek and longtime friends of Bill and Lynne Hybels; and former Willow staff member Leanne Mellado, whose husband Santiago “Jim” Mellado was the longtime head of the WCA and is current president of Compassion International.

The church’s elders have defended their senior pastor, citing three investigations into Hybels that found no misconduct. They also denounced the Tribune report in an email to the congregation, saying it was “based on false allegations resulting from a campaign by a group of former church members who want to damage the reputation of our church and our senior pastor.”

Steve Carter and Heather Larson, who were named to succeed Hybels last fall, will immediately take over as lead pastors.

At Tuesday’s meeting, Larson said she was grateful for women leaders at Willow in the past—seeming to refer to Beach and others who have made allegations. She hopes tonight’s decision will open the door to reconciliation.

Larson also addressed the women in the congregation.

“I know many of you are confused or frustrated,” she said, saying media accounts did not match many congregants’ experience. “We can respect someone’s story and stand up for our own. You are strong. You have your own voice. For all of us, as women and men, we will put our best energies on moving ahead.”

Tom De Vries, president of the Willow Creek Association (WCA), was at the church Tuesday when Hybels stepped down. A week earlier, he said, the pastor had voluntarily stepped from the WCA board at a regular board meeting.

“He came into the conversation and was burdened by all the things that were going on and how the controversy was affecting the Global Leadership Summit,” said De Vries.

Some of the simulcast sites were concerned about Hybels continuing on as host, and didn’t know if they could promote the event if he remained part of it.

For now, it’s not clear who will host the summit this year. Several speakers from the past have called and offered to help out.

De Vries said that Hybels could return to the WCA and the leadership summit in the future—after a time away.

In order to return, he said, Hybels and his counselors would have to come up with specific outcomes—and show proof that those outcomes had been met.

De Vries said he’s seen some contrition with Hybels behind the scenes. More is likely needed, he said. That’s something he hopes Hybels’s counselors and advisers will work on. Hybels would also need to make amends—where needed—to anyone he has hurt.

“We hope there will be a mending of the wrongs that have been done,” he told CT.

Several congregants told CT they did not view Hybels’s comments on regrettable communications or unwise situations as admitting wrongdoing as alleged by the women who have come forward with their stories. “He’s always been a man of character,” said Roberta Dusek, who has been attending Willow Creek for 34 years. “He’d never put himself in a situation where he was alone with the opposite sex.”

Schmidt, the longtime elder at Willow Creek who has criticized how the church has handled allegations against Hybels, said that she was saddened but not surprised by tonight’s event.

She was disappointed that Hybels made no specific mention of people he has hurt or specific things he did wrong.

It was all too general, she said. There was no contrition by Hybels, no confession, and no asking for forgiveness from those he harmed.

“I don’t think that was much of an apology,” she said. “An apology with no contrition is no apology at all.”

Schmidt was also troubled by Hybels’s plan to take time off and then come back to the church.

“Bill laid out his own restoration path there,” she said. “That is not how a church should be run. He dictated all the terms of what he is going to do. I don’t see that as being biblical.”

CT

CTThe Willow Creek founder’s early departure still leaves questions unanswered. Several of the women who made their accusations against Hybels public, as well as the former church leaders who defended their claims, have continued to restate their concerns in recent days and call for a more thorough investigation.

“It takes great courage for women to tell their stories,” pastor and author John Ortberg wrote in a blog post last week. “In this case, the tremendous courage of several women has been met with an inadequate process that has left them without a refuge and with no way to be assured of a fair hearing.”

He called Hybels’s initial claim that Ortberg and others colluded to bring up the allegations “untrue and a diversion.”

In a statement posted online today, Schmidt, the longtime elder, countered Willow Creek’s recent claim that she said she heard “not an inkling” of allegations against the senior pastor. She said she was clear about her concerns when she brought one woman’s story before the elder board.

Many who have raised concerns or called for further accountability cite their respect for Willow Creek and its legacy as part of their motivation. Cases like Hybels remind Christians of the messiness of ministry—of how even flawed people do great things for God, observed Amy Reynolds, who studies female leadership as a sociologist at Wheaton College.

“The way that these situations often get portrayed is that there are good people and bad people,” she said. “But there is nuance. You can say, look, this person did some good things and some bad things. We want to hold people accountable for the bad things.”

One of the women who shared her story in the Tribune, former Willow Creek staff member and vocalist Vonda Dyer, detailed her experience even further in a blog post published on Sunday.

Dyer, who traveled with Hybels and other church staff overseas, characterized Hybels’s behavior as “grooming,” writing that he often complimented her on her looks and pressured her to spend time alone with him.

Before Tuesday’s announcement, some of Hybels’s friends and colleagues had come forward to defend his character. “I haven’t seen anything that would disqualify him from ministry,” said Rick McDaniel, pastor of Richmond Community Church in Virginia.

He said the accusations about his mentor were hard to hear and that the alleged behavior seemed unwise for a pastor, but that he also trusted Hybels’s commitment to personal ethics. He had confidence that if Hybels had done anything wrong that he would admit it and try to make amends. “I believe that will happen,” he said.

The early retirement puts an end to Hybels’s decades-long career at Willow Creek, where he pioneered new approaches to church life, Christian leadership, and ministry.

He first made his mark in the early 1970s as a youth pastor fresh out of college, when he and Dave Holmbo started a program called Son City at Park Ridge’s South Park Church near Chicago. Featuring contemporary music and drama combined with Hybels’s preaching, the group grew from a few dozen to more than 1,200 in a few years.

Eventually Hybels and friends from Son City decided to found a new church. They rented out the Willow Creek Theater on Sunday mornings, funding the new venture by selling tomato plants door to door.

The church was so successful, it eventually launched the so-called seeker-sensitive movement—a church model aimed at attracting newcomers to the faith. Willow Creek’s success made Hybels one of the most influential American pastors of the past 40 years.

That movement revolutionized how many evangelical churches operate; it transformed Sunday morning services from times of spiritual growth for church members to outreach events aimed at attracting newcomers.

Starting Willow Creek took a toll on Hybels and other leaders. In their book, Rediscovering Church, his wife, Lynne Hybels, describes how those early years nearly ruined the couple’s marriage.

And the church nearly foundered after an incident known as the “Great Train Wreck,” when a key leader left the church after being accused of having several affairs. Some church members blamed Hybels for ousting the departed leader, while others were angry that church leaders had failed to inform them of the alleged misconduct.

“The dream is over,” Lynne Hybels recalls her husband saying after discovering this misconduct, which stalled building plans and fundraising. But the church recovered, as did Hybels’s dream.

Willow Creek became one of the 10 biggest congregations in America, and Hybels grew in national prominence. Starting in 1992, WCA’s annual Global Leadership Summit, hosted by the pastor and featuring top business figures, introduced new strategies to inspire hundreds of thousands of Christian leaders.

Schmidt has called for a thorough, independent investigation of Hybels’s conduct. She said that she knew of two incidents involving Hybels, but thought both had been dealt with. “I want the truth to come out,” she said. “That’s the only way true healing can begin.”

Tuesday’s meeting began like countless services at Willow Creek, with members making their way to the seats they sit in every Sunday and standing beside their church family for worship. But as soon as Hybels stepped on the stage, the tone shifted from friendly chatter, laughter, and neighborly hugs and handshakes to rapt attention.

The pastor’s remarks repeatedly pointed to the good of the church he founded and the future of Willow Creek.

Jay Rasmussen, a Willow Creek member who was not expecting Hybels’s resignation, sat in the back row of the auditorium processing the news. “It does force us to look at the church not as one person but as a place God has blessed with his leadership,” said Rasmussen.

The songs that began the gathering—“Cornerstone” and “In Christ Alone”— underscored this message, as the members sang out, “I find my strength, I find my hope, I find my help in Christ alone.”

Larson told the congregation, “It’s not the end of Bill’s story. It’s not the end of Willow’s story. It’s certainly not the end of God’s story. God is still writing new chapters for all of us.”

Additional reporting by Kate Shellnutt in South Barrington, Illinois.