Among Billy Graham's greatest contributions to evangelicalism was the way he defused prejudice to bring people together. Perhaps more than any other high-profile American figure in the 20th century, Graham challenged Christians to look beyond worldly divisions and remember their call to the ministry of reconciliation.

In the early 1950s, a few years before Martin Luther King Jr. and the civil rights movement garnered the national spotlight, Graham was talking about the church's obligation to overcome the race problem in America. “The ground at the foot of the cross is level,” he said, “and it touches my heart when I see whites standing shoulder to shoulder with blacks at the cross.”

Decades later, in a 1993 Christianity Today article, Graham was still on message. He wrote, “Of all people, Christians should be the most active in reaching out to those of other races.”

To be sure, Graham was never at risk of being mistaken for a civil rights activist. His proclivity for caution and incremental steps on controversial matters was another one of his legacies to the evangelical movement. Still, for a white evangelical of his stature to put the issue of race relations on his ministry's agenda was quite remarkable.

The Evangelist's Evolution

Graham did not, of course, arrive on the scene 60 years ago with a fully developed theology of inclusion. It took him years to finally shake off the rituals of American apartheid that defined the era of his national emergence. For instance, during the early years of Graham's ministry, he freely accepted the custom of segregated seating at his Southern crusades.

Soon, Graham's every move drew media attention. Reporters inquired about the negligible participation of blacks in his crusades. Did holding segregated events jibe with the message he was preaching?

By 1952, the 34-year-old evangelist was deeply distressed by the racial prejudice he saw among Christians and wondered whether his failure to speak up was part of the problem. Graham saw an opportunity to take a stand during his Jackson, Mississippi, crusade. When Governor Hugh L. White insisted that Graham hold separate services for whites and blacks, the evangelist refused.

“There is no scriptural basis for segregation,” he told the crusade audience. “It may be there are places where such is desirable to both races, but certainly not in the church.” Though defiant, Graham still acquiesced on the issue of segregated seating.

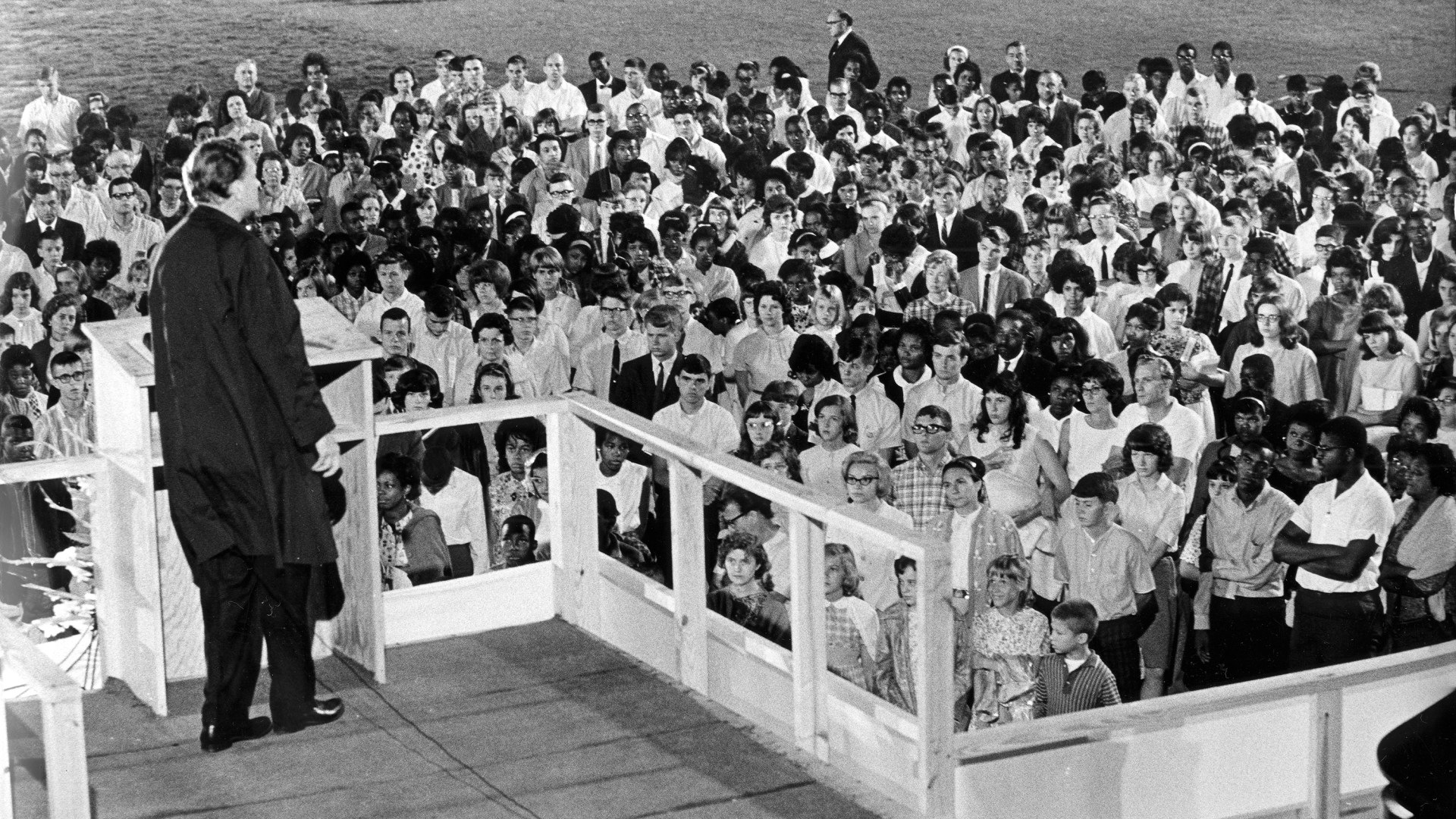

A year later, however, he stunned the sponsoring committee of his Chattanooga, Tennessee, crusade. Graham railed against the practice of segregated seats. Then the committee watched in astonishment as he personally tore down the ropes separating the black and white sections at the arena.

From then on, Graham took cautious but deliberate steps towards dismantling the barriers of racism in the church.

In 1957, he invited King to say a prayer at his epic New York City crusade at Madison Square Garden. He also began integrating his ministry internally by adding his first black team member, Howard O. Jones, a young pastor from Cleveland. Soon Graham was working regularly with African American churches within the communities where his crusades were held. That same year, at a black church in Brooklyn, Graham said publicly for the first time that anti-segregation legislation might be necessary to bring an end to discrimination.

Perseverance Despite Pressure

In their book The Preacher and the Presidents, journalists Nancy Gibbs and Michael Duffy write:

Graham found himself caught between the growing activism of the mainstream Protestant churches with whom he worked and the hostility of fundamentalists whose theology was more congenial to him but who disapproved of his integrated crusades and his ecumenical outreach. That hostility, which had been growing for years, reached such a point by 1966 that Bob Jones Jr. forbade his students to attend Graham's Greenville, South Carolina, crusade or to pray for its success, and denounced Graham as a false teacher who “is doing more harm to the cause of Jesus Christ than any living man.”

“What Billy did was radical,” said Howard Jones, who died in 2010. “He weathered the barrage of angry letters and criticisms. He resisted the idea of playing it safe.”

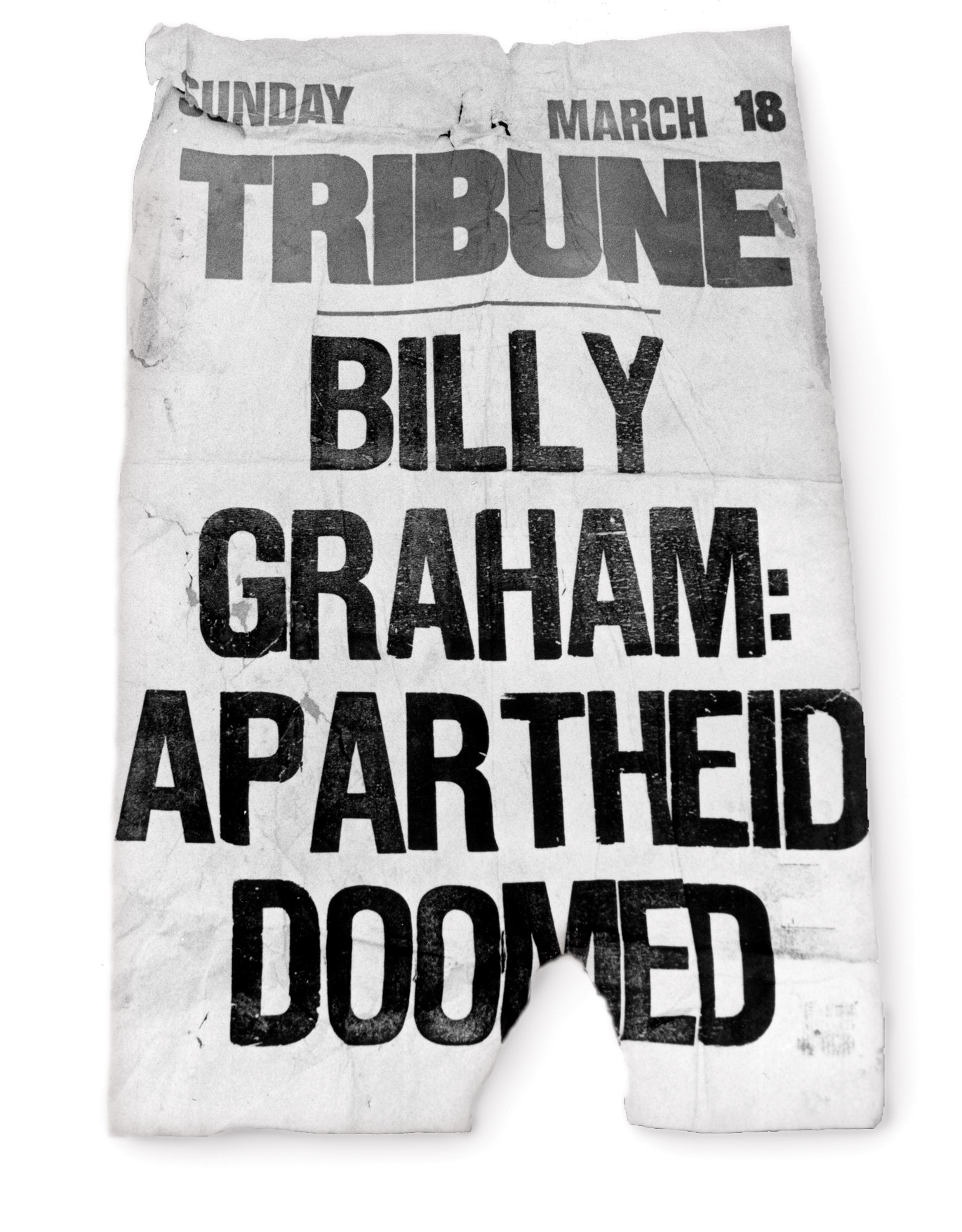

Graham's evolving ethic of social justice extended beyond US borders as well. In the early '60s, years before boycotts of South Africa came into vogue, Graham took a pioneering stand against that country's system of white supremacy. In his autobiography, Just As I Am, he wrote: “Churches in another nation, South Africa, strongly urged us to come, but I refused; the meetings could not be integrated, and I felt that a basic moral principle was at stake.” Religion scholar Michael G. Long says Graham's 1960 boycott blazed a trail for the many boycotts that followed.

This did not mean that Graham was fully on board with the methods of the civil rights movement that was upending America's conscience in the '60s. Though friendly with King, Graham was wary of the kind of civil disobedience practiced by his followers. Echoing a mantra that has long helped some evangelicals justify social inaction, Graham said, “No matter what the law may be—it may be an unjust law—I believe we have a Christian responsibility to obey it. Otherwise, you have anarchy.” King, in response, channeled St. Augustine: “An unjust law is no law at all.”

At the height of the movement, Graham sometimes struggled with balancing his theme of spiritual change through the message of the gospel with the more holistic brand of transformation sought by black activists. “Some extreme Negro leaders are going too far and too fast,” Graham said in the early '60s. “Only the supernatural love of God through changed men can solve this burning question.”

Faithful to the End

In spite of such shortsighted misgivings, the evangelist held a steady course in his opposition to racism and advocacy of cultural diversity among Christians. Over the years he consistently spoke out against racial injustice and gradually added more people of color to his organization.

Perhaps Graham's ongoing heart for racial reconciliation is best capsulized in his handling of the controversy that confronted him during one of his final crusades. In June 2002, Graham arrived in Cincinnati, Ohio, against a backdrop of simmering racial unrest.

A year earlier, an unarmed African American had been shot and killed by the Cincinnati police. Community activists called for a boycott of the city. Many national entertainers canceled engagements in Cincinnati as a show of support.

When activists demanded that Graham observe the boycott and cancel his crusade, he gave it serious thought. But after much discussion and prayer, Graham and his team decided it was important for the rally to continue as planned. And many African American church leaders in the community agreed. In the end, the crusade became a shining model of grace and reconciliation for a city in need of healing.

“It was one more time that Billy followed his heart and did what he believed to be right, regardless of public or political pressure,” says Jones. “He always was faithful to what God was calling him to do.”

Edward Gilbreath is author of Reconciliation Blues: A Black Evangelical's Inside View of White Christianity.