For most of Wheaton Academy’s 165-year history, it was a boarding school. Boarding was ended in the 1980s, then brought back—structured as host families—in 2006.

“China had just started its student visas a year or two before,” said Brenda Vishanoff, vice principal for student services and student learning. The first year, the Christian high school near Chicago had two international students—one from China and one from the Central African Republic. In later years, the number jumped to 8, then 16, then 37.

Soon, Wheaton Academy had more international students than it could take, so it opened a network to place them with other Christian schools. Most of those students—including 45 of the 60 enrolled there this year—have been from China.

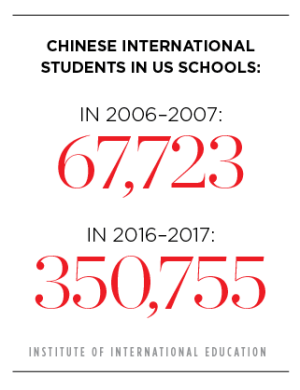

The growth reflects a national trend. From 2004 to 2016, the number of international high school students in the United States more than tripled, according to a recent report by the Institute of International Education (IIE). Nearly three-quarters of international students enrolled on an F-1 visa (good until graduation) in 2016; of those, more than half were Chinese (58%).

Chinese parents send their children to America out of frustration with their own highly competitive and narrowly tracked education system, Vishanoff said. As the Chinese economy grew, more parents had the resources to send their child to the US for college. Soon realizing that an American high school education eases the transition to college—and perhaps makes their child’s application more attractive—parents began sending them earlier.

Because public high schools only allow J-1 visas (good for a year or less), nearly all international high school students on F-1 visas enroll in private high schools, according to IIE. And because most of America’s private high schools are religious, 58 percent of all international high school students enroll at one. And nearly all of those schools are Christian, according to IIE data.

But only about 5 percent of China is Christian, according to the Pew Research Center. More than half of its citizens are unaffiliated (52%) like its atheist government.

Even so, Chinese parents aren’t wary of Christian schools. “We hear from nonbelieving Chinese families that they think their student might be safer and better cared for at a Christian school,” Vishanoff said.

In the past seven years, Wheaton Academy’s WAnet has placed 400 students. It’s not alone—700 members of the Association of Christian Schools International (ACSI) now enroll international students. That’s up from “just a few” 10 years ago, according to assistant vice president Erin Wilcox, brought on by ACSI two years ago to help support those schools. “Schools bring the kids over first, and then realize how hard it is.”

Schools have to train teachers to accommodate students from a different culture who may not speak English fluently. They have to help students acclimate and learn the language, train domestic students to welcome and include students who aren’t like them, and teach host families to provide care for homesick and culture-shocked teenagers.

That adds up. Wheaton Academy charges about $17,000 in tuition and fees for a domestic student; an international student’s tuition, fees, and boarding cost almost $50,000. WAnet’s 11 schools charge between $34,000 and $50,000 for such students.

For Christian schools running on shoestring budgets, such amounts can look like school-savers. “If a superintendent says, ‘I want 50 international students because it will help my budget,’—yeah, it will,” Wilcox said. “But you’re going to spend a good amount of that money on the needs of the students.

“It’s hard for some schools to understand,” she said. “They see the money first and then realize slowly that it’s hard to educate these kids and to train the teachers.”

Adding international students changes a school’s culture. “You get a different perspective,” said Trixanna Wang, who works with such students at Pella Christian High School in Iowa. “In comparative religion classes, our Chinese students are often willing to talk about Buddhism from a personal or cultural perspective. In government or history classes, kids raised in a Communist country tell about that experience. There is definite enrichment.”

And with Chinese students attending a Christian school, living with a Christian host family, and often going to a church on weekends, the opportunity for evangelism is enormous. Pella Christian has seen baptisms each of the past two years. Wheaton Academy has also seen kids come to Christ.

“We often ask the parents … to make sure they’re open to their children becoming Christian,” Vishanoff said. “Often kids will ask permission from their parents before they’re baptized. Most are very open to their children choosing their own religion.”

Serving Chinese high school students is “an unprecedented opportunity for Christian schools to be extending their mission in a way we never would have considered 10 years ago,” said Ruth Kuder, chief education officer at Eastern Christian School in New Jersey. “When we serve [international] students, we’re also serving families and communities. The influence extends far beyond the students we have in front of us.”

It’s an opportunity that may be in jeopardy. Since 2014, the growth rate of international students has fallen from 8 percent (2014) to 3 percent (2015) to 1 percent (2016).

Part of that may be attributable to China’s investment in its own universities or to the slowing growth of China’s economy. But the parental hesitations Vishanoff hears most are about the political climate and physical safety in America. “It does worry some of our parents that maybe the US isn’t as open to immigrants as before,” she said.

Another concern is mass shootings, she said. “We live very close to Chicago, where the murder rate is high. I try to proactively let them know how safe this school is, but I do get questions.”

It’s hard to find a trend line. “The next five years are somewhat unpredictable,” WAnet director Benjamin Euler said. Australia, the United Kingdom, and Canada also draw thousands of Chinese international students. Then again, no one would have predicted the last 5 to 10 years either. “In the early 2000s, there were a few thousand international students in all the Christian high schools combined,” Euler said. “Now we’re up to 70,000-plus in all private schools.”

“It’s a reverberating effect,” he said. “We may not see it in the first year, or even a few years later, but ultimately there is going to be a lot of change in the world as a result of students coming here to study in Christian schools.”