In this series

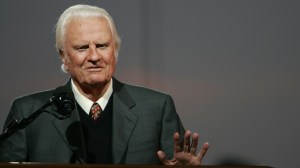

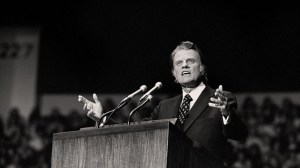

In 1974, Billy Graham convened an enormous conference in Lausanne, Switzerland.

“I traveled the whole world meeting such wonderful leaders,” Graham later told Lausanne global executive director Michael Oh. “But I found that they didn’t know each other.”

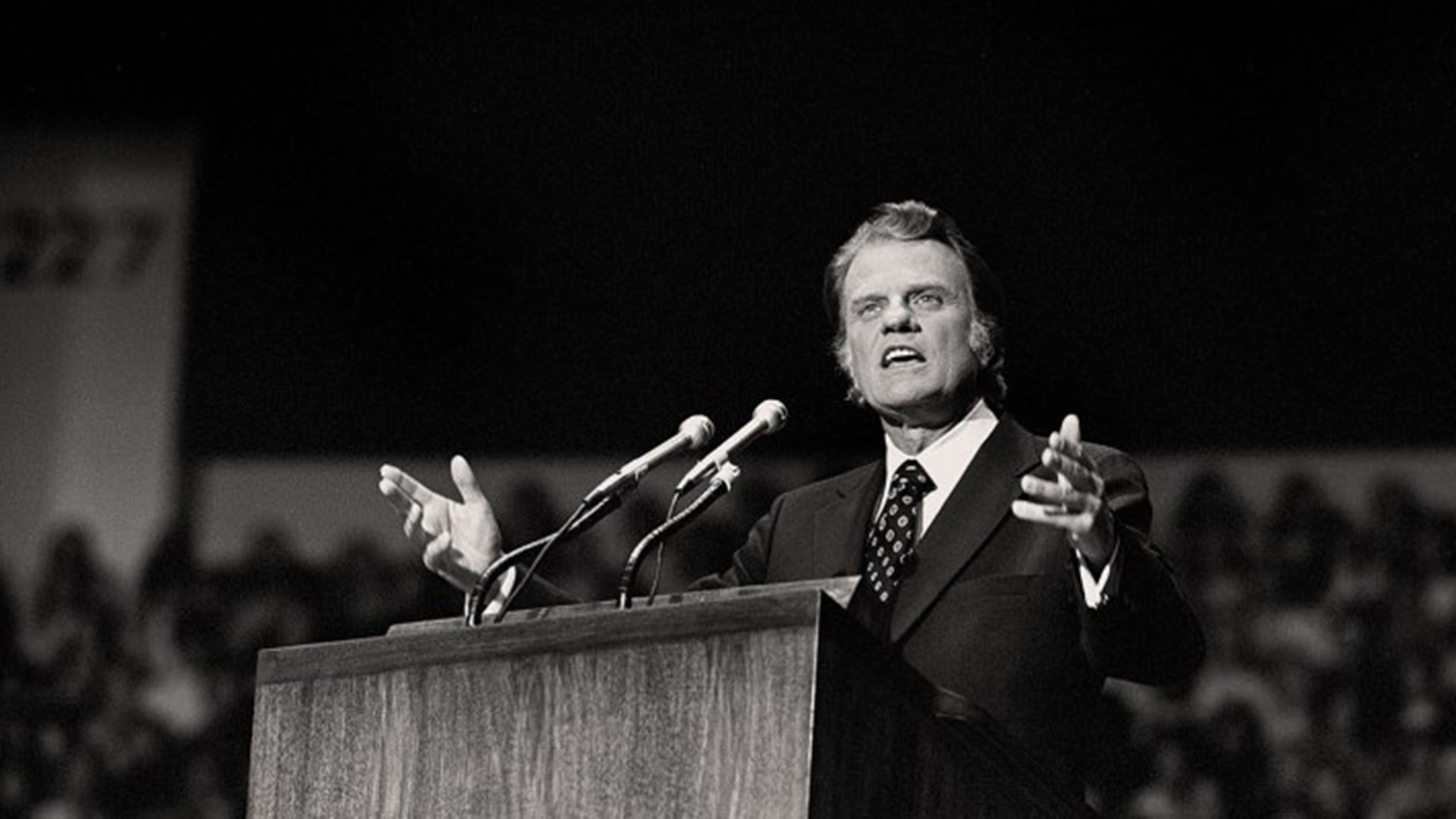

Graham wanted to assess the way political, ideological, and theological world issues affected evangelism, and to bring evangelical leaders to a common vision for both evangelism and social justice. He invited about 2,400 evangelical leaders from 150 countries.

The meeting turned out to be outrageously important. Not only did the participants make up “possibly the widest-ranging meeting of Christians ever held” and signal the rising strength of conservative Christians worldwide, it also delivered unity on the most divisive issue of the day—whether social justice should be as highly prioritized as evangelism.

And it kicked off the Lausanne Movement.

“No one else did as much to turn evangelicalism into an international movement that could stand alongside—and ultimately challenge—both the Vatican and the liberal World Council of Churches for the mantle of global Christian leadership,” wrote George Washington University professor Melani McAlister for The Atlantic. Her forthcoming book is The Kingdom of God Has No Borders: A Global History of American Evangelicals.

“He used his status as the most important religious figure of the 20th century to help lead American evangelicals into a more robust engagement with the rest of the world,” she wrote.

In some ways, the first Lausanne conference was the culmination of a meeting 20 years earlier, when Graham was first introduced to British evangelist John Stott at Cambridge University.

The two became close friends during a mission at the school.

“The first time I visited Billy at his old log home with Leighton [Ford], the very first thing Billy asked me was ‘How’s John?’” remembered Doug Birdsall, honorary co-chair of the Lausanne Movement. “This should not have surprised me because just a year earlier when I first met John Stott in London on Lausanne-related matters, his first question had been, ‘How’s Billy?’”

Stott was among the small group of leaders Graham gathered in Montreaux, Switzerland, in 1960 to mull over how to unite evangelicals globally. The answer: Gather around evangelism, the only word that would unite them, Graham decided.

Out of the Montreaux meetings grew the 1966 World Congress on Evangelism, which drew 700 participants, including Stott.

And out of the 1966 Congress grew the Lausanne Congress, organized and funded almost entirely by the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association. Graham and Stott both spoke, emphasizing the urgency of evangelism and addressing the argument over whether evangelism should be valued more highly than social justice issues.

They did it: Graham as “the indispensable convener,” and Stott as “the indispensable uniter.” The Lausanne Covenant brokered peace between the two sides (“we affirm that evangelism and socio-political involvement are both part of our Christian duty”) and gave walking orders for future partnerships in evangelism.

The Congress also gave walking orders to a Continuation Committee, which included both Stott and Graham and met in Mexico City in 1975. There, the Lausanne Movement was fleshed out, with Graham’s brother-in-law Leighton Ford elected as chairman in 1976.

At the same time, Graham was supporting a global outlook at the World Evangelical Alliance (WEA).

The week after the Lausanne Congress, in which the WEA was heavily involved, Graham “took time to attend the WEA General Assembly nearby at Chateau d'Oex,” the WEA stated. It wasn’t the first time he’d given input: in 1968, “at a time when the WEA needed added impetus, he stepped in and provided resources for the relaunch and internationalization of the work.”

Expanding evangelism to the entire world was immensely important to Graham. In one interview, he told Newsweek that the outcome of the 1974 Lausanne Congress may have been his most enduring legacy.

Fifteen years later, a second Lausanne Congress was held in Manila, Philippines; about two decades after that, a third was held in Cape Town, South Africa.

“The world has changed greatly” since the first Congress, Graham told the Cape Town attendees via fax. “But in all your deliberations, I pray you may never forget that some things have not changed in the last 36 years—nor will they ever change until our Lord returns.”

Those are “the deepest needs of the human heart,” the gospel, and Jesus’ command to “go into all the world and proclaim the gospel,” he stated.

The numbers bear him out. While there was disagreement on the use of alcohol or how literal the Bible is, nearly all of the Cape Town leaders told the Pew Research Center that “Christianity is the one, true faith leading to eternal life” (96%) and that “the Bible is the Word of God” (98%).

When Blair Carlson, who directed the Third Lausanne Congress, met with Graham to report how it went, he began with the program, the speakers, and the numbers.

“Mr. Graham interrupted me and said, ‘Just tell me, are the Congress participants telling the people in their countries about the Lord Jesus Christ?’”

The numbers again bear him out. A 2011 Pew study found that of the nearly 2.2 billion Christians in the world, no one place has a majority.

Christians are “so far-flung, in fact, that no single continent or region can indisputably claim to be the center of global Christianity,” Pew stated.

No small part of that can be credited to Graham, who preached to some 215 million people in 185 countries and territories. His largest live crusade was to 1 million people in Seoul, South Korea, and he inspired tens of thousands to come to Christ in Hong Kong. He was anti-communist, but visited both North Korea and Russia in attempts at opening doors for peace.

“Christ belongs to all people,” Graham preached in Johannesburg in 1973. “He belongs to the whole world. … I reject any creed based on hate … Christianity is not a white man’s religion, and don’t let anybody ever tell you that it’s white or black.”