If President Donald Trump really was pro-life, Pope Francis said on Monday, then America’s chief executive wouldn’t end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program.

“If he is a good pro-life believer, he must understand that family is the cradle of life and one must defend its unity,” the pontiff told reporters. Separating children from their parents “isn’t something that bears fruit for either the youngsters or their families.”

This stance shouldn’t surprise anyone, as one of the distinctive features of Catholic theology is what’s been described as a “consistent ethic of life.” In other words, protection and preservation at all stages of life. That’s why the Catholic church’s “seamless garment” condemns abortion, the death penalty, assisted suicide, and embryonic stem cell research.

[Editor’s note: CT has reported how many evangelicals feel the same. Leaders have advocated for life not only around abortion, euthanasia, and the death penalty, but also related to refugees, the elderly, and #BlackLivesMatter.]

But almost no Americans—including Catholics and evangelicals—hold to a consistent ethic of life, according to the General Social Survey (GSS).

For my analysis, I relied on three questions asked by the GSS, the gold standard of social science research due to its massive sample size, large question set, and 40 years of data. They were:

-

Please tell me whether or not you think it should be possible for a pregnant woman to obtain a legal abortion if: The woman wants it for any reason? (Favor/Oppose)

-

Do you favor or oppose the death penalty for persons convicted of murder? (Favor/Oppose)

-

Do you think a person has the right to end his or her own life if this person: Has an incurable disease? (Yes/No)

Below is a Venn diagram of how the American population feels about these issues. A fair number of respondents are opposed to abortion (38%), but are also in favor of the death penalty and assisted suicide (19%).

However, when one moves to the overlapping portions of the diagram, the percentages drop off drastically. The number of Americans who ascribe to a consistent ethic of life, as measured by the three GSS questions, is approximately 4 percent. Even if we relax the standard to only two of the three issues, still less than a quarter of Americans would qualify as consistently choosing life (23%).

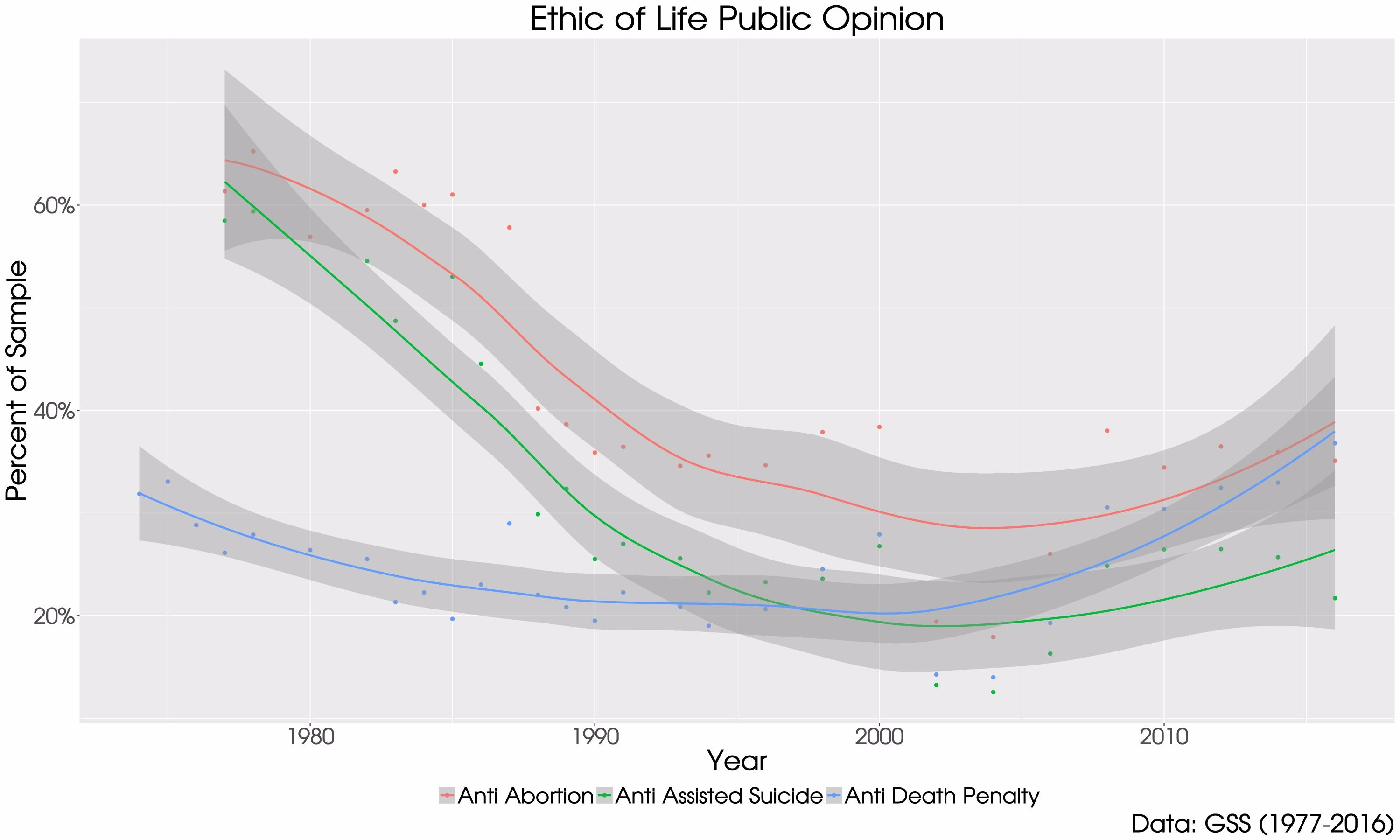

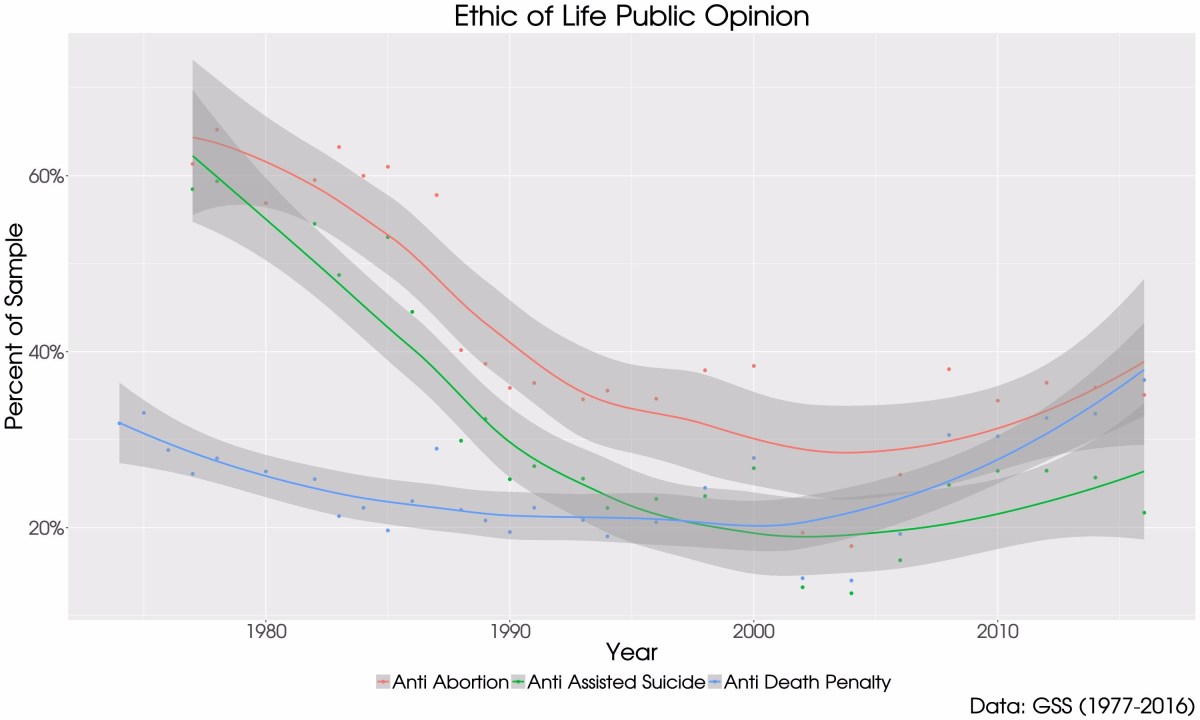

Public opinion has shifted over time. Opposition to the death penalty was relatively consistent over the last 30 years; since the early 2000s, it has reached almost 40 percent. The other two issues saw a significant shift between 1977 and 2000. Though opposition in both cases has been increasing again in the new millennium, overall the American public has become more supportive of allowing a woman to receive an abortion for any reason as well as allowing terminally ill individuals to end their lives (both by 20 to 25 points more).

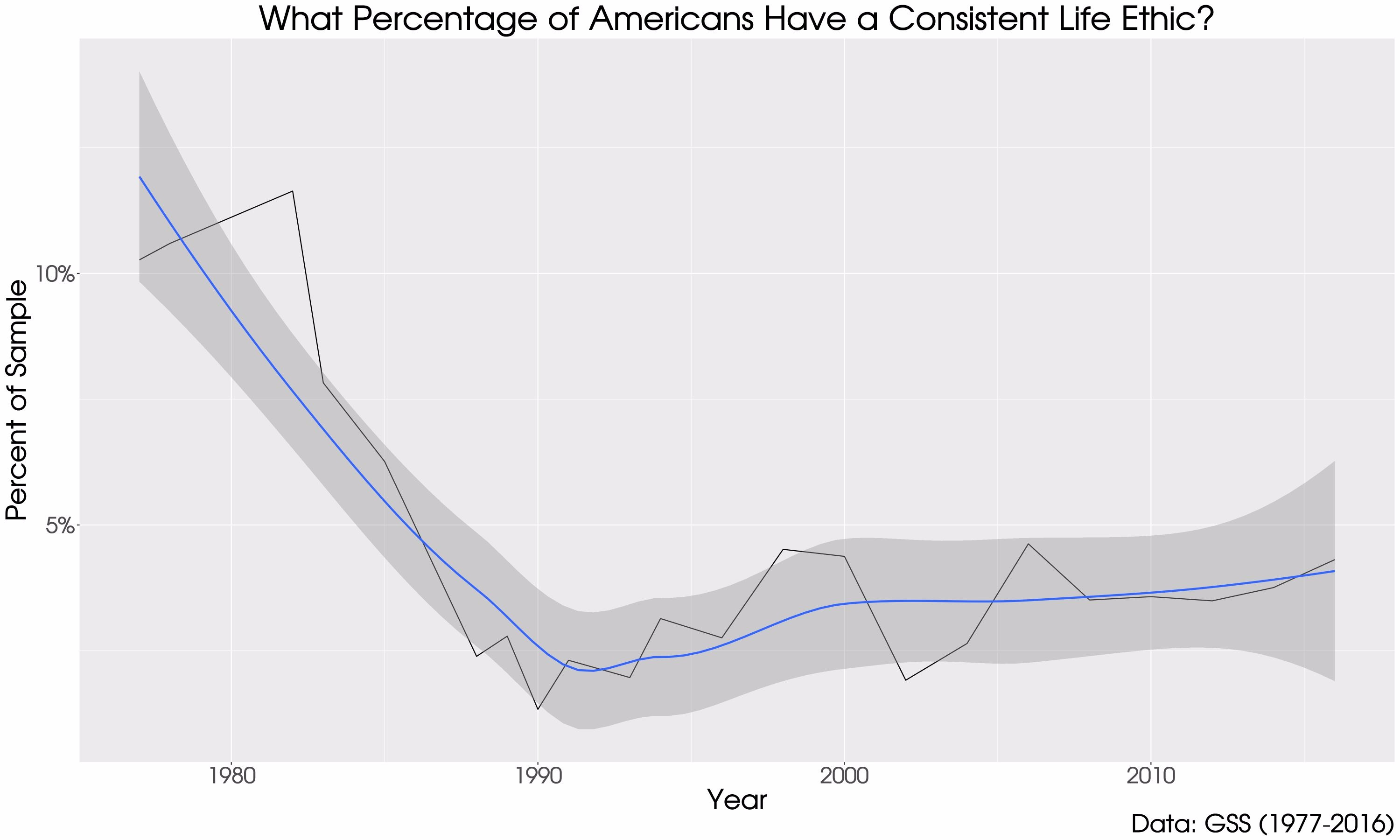

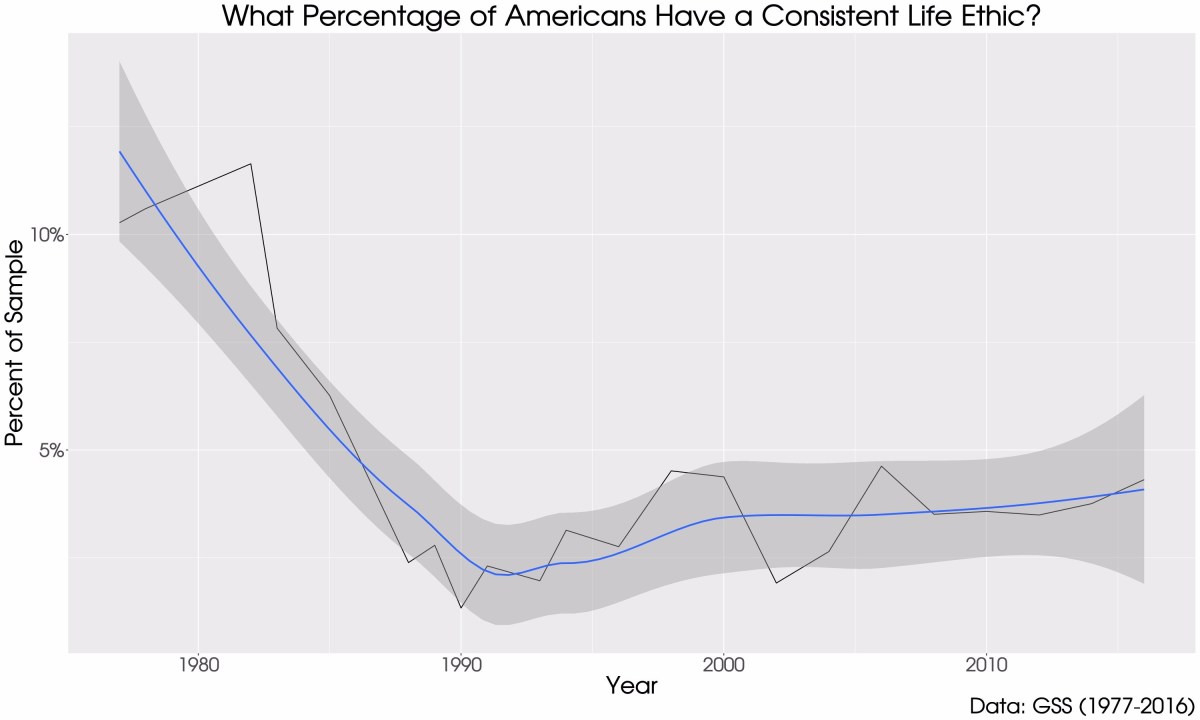

The chart below also tracks how the number of individuals holding to a “consistent ethic” have changed over the last four decades. Between 1977 and 1990, the number of those opposing euthanasia, abortion, and the death penalty dropped from more than 10 percent of the population to about 3 percent. This number has risen only slightly since that time period; in no year since has it risen past 5 percent.

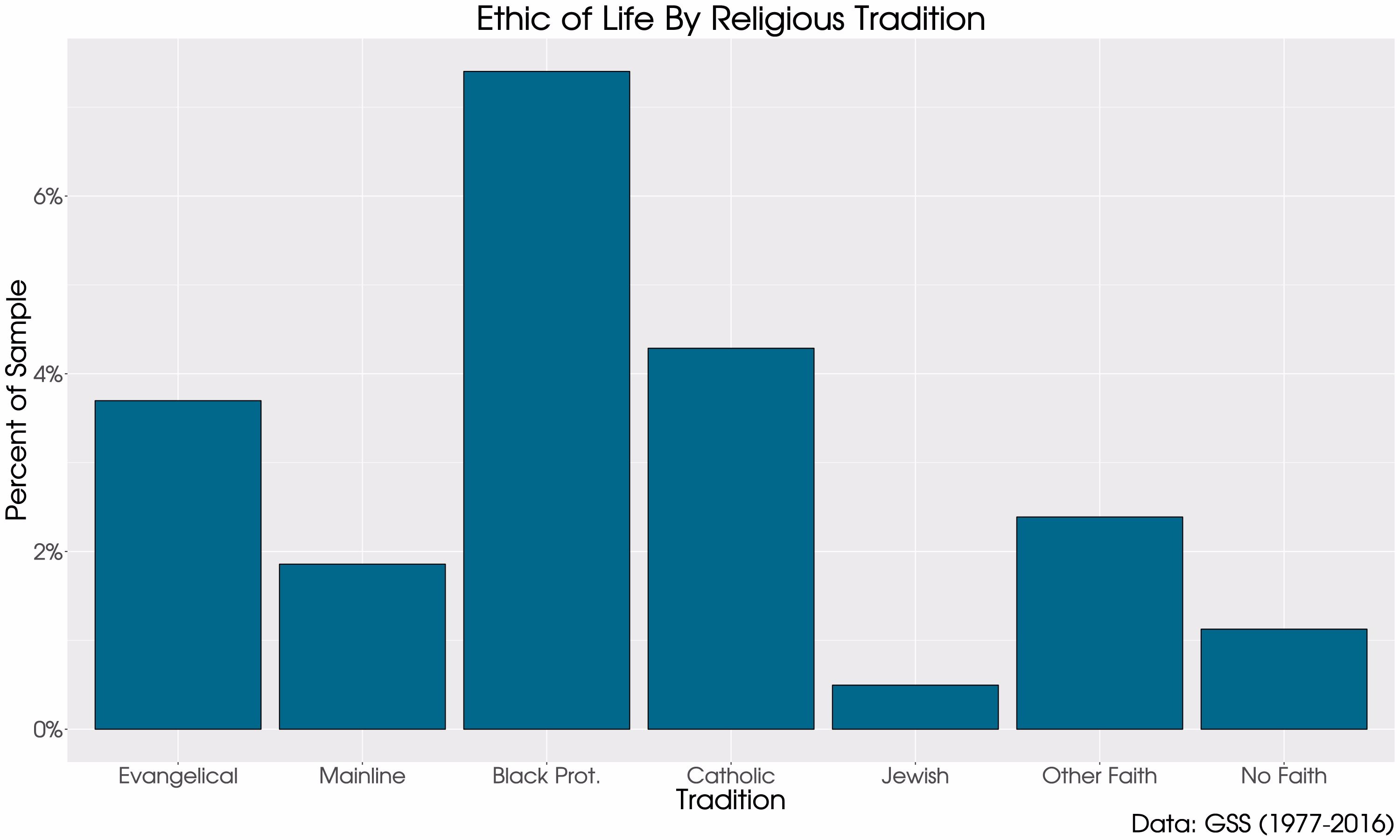

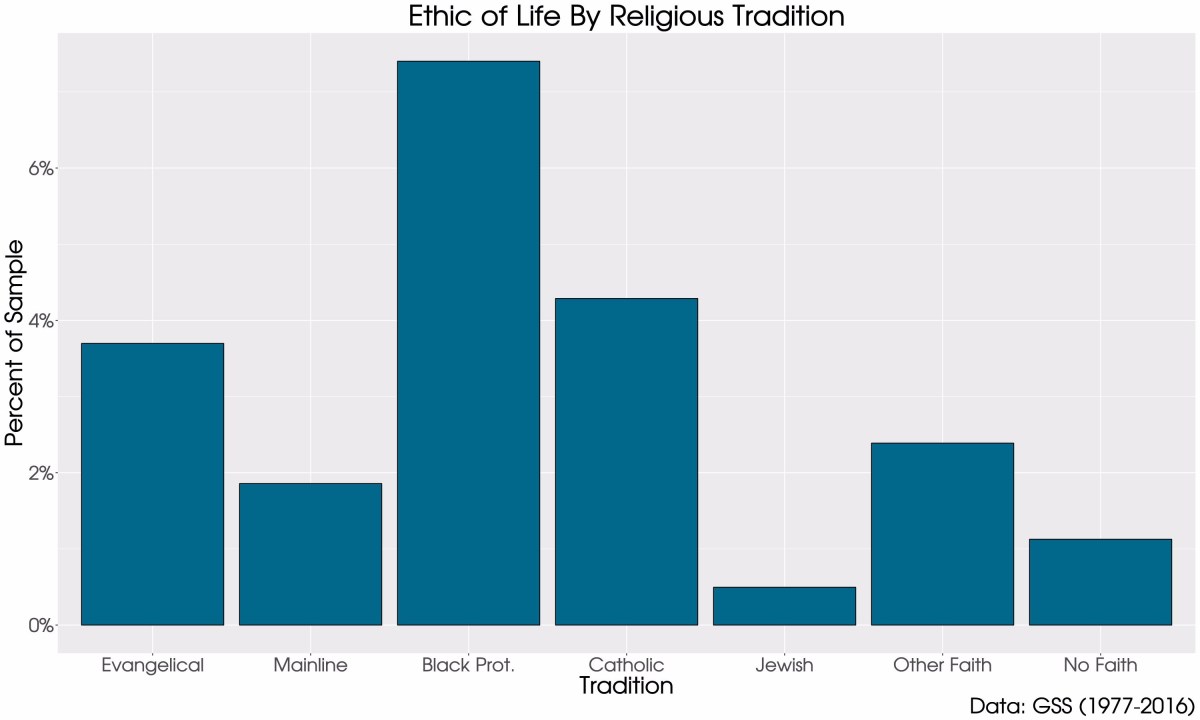

Despite Francis’s admonitions, American Catholics are not the most likely to believe in a consistent ethic of life. Instead, it’s black Protestants, with more than 7 percent qualifying under my GSS measurement. (While evangelicals consistently oppose abortion, many of them are also in favor of the debated death penalty.)

The GSS data suggest that almost no one in the United States holds a philosophically consistent point of view on issues relating to life. Instead, most Americans take things on a case-by-case basis. Americans are a pragmatic bunch, evaluating an issue on its merits and in isolation from other issues.

In addition, John Zaller argued in “The Nature and Origin of Mass Opinion” that individuals will answer survey questions with whatever response is on the top of their head, which means that they are easily manipulated and lack any sort of consistent belief system. Both of these ideas might help explain why there are so few Americans with a consistent ethic of life.

Ryan P. Burge is an instructor of political science at Eastern Illinois University.