In this series

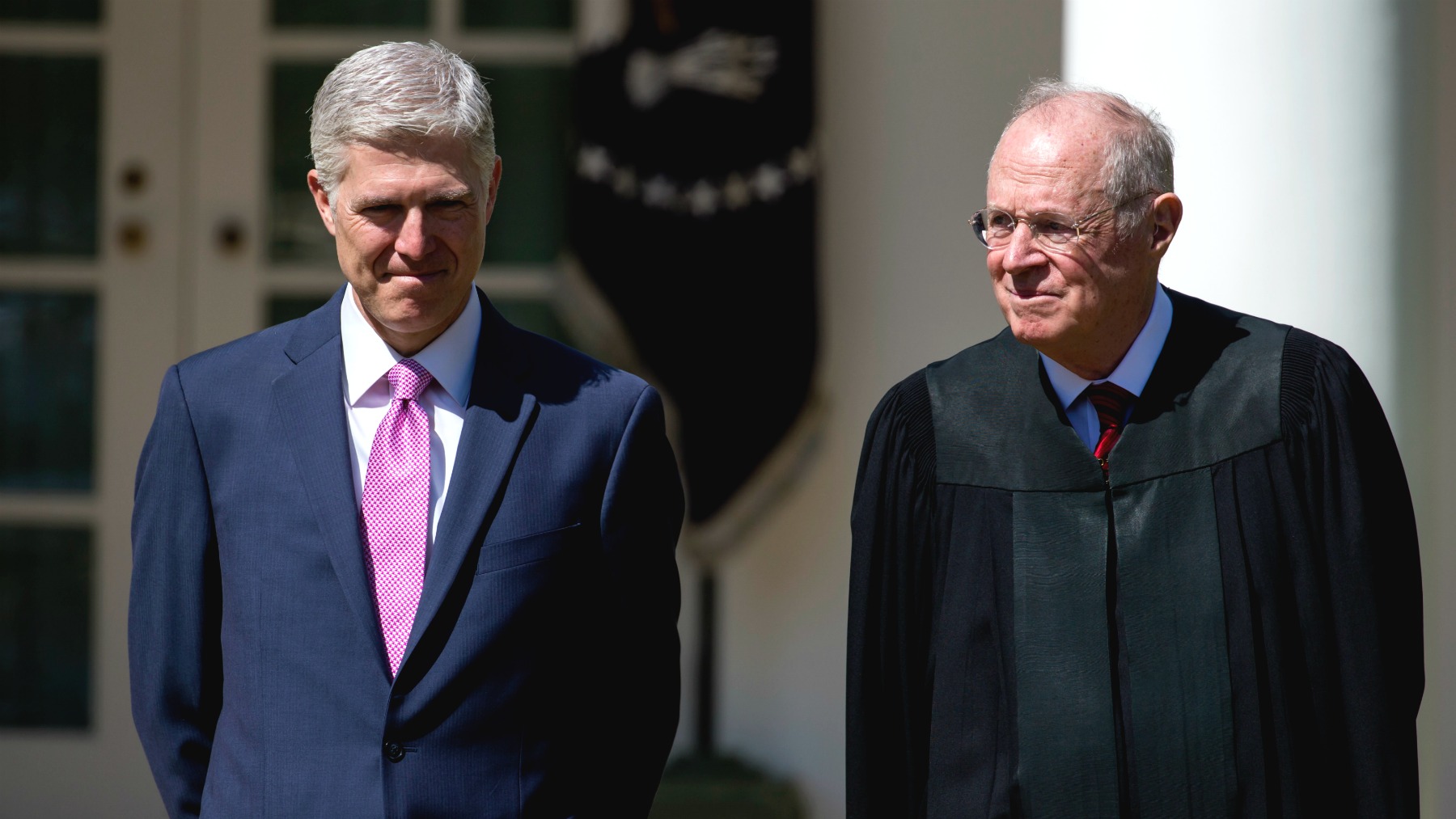

The US Supreme Court waited for Neil Gorsuch before hearing its biggest church-state case of the year.

Now, for the sake of Christian schools across the country, American evangelicals are hoping the new justice will continue his pattern of siding with religious groups’ First Amendment rights.

More than 15 months after the high court took on a case involving a Missouri church denied a state grant to make its preschool playground safer, the nine justices will hear oral arguments on Wednesday in Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia v. Comer, their only religious liberty case this term.

“The church isn’t asking for favorable treatment. It is asking to be treated the same as every other nonprofit,” said David Cortman, senior counsel for Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF), which is representing Trinity Lutheran in court.

The case tests how far officials can take the separation of church and state, and whether constitutional principles can be used to justify what Cortman calls “worse treatment” for religious organizations.

Depending on how broadly the court rules, the dispute over this Lutheran school playground could determine the future of state funding to religious schools, which has become a particularly hot issue amid the recent push for school choice.

Dozens of religious organizations have sided with Trinity Lutheran, including the National Association of Evangelicals, the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC), the US Conference of Catholic Bishops, and the American Association of Christian Schools. They view the state of Missouri’s decision as religious discrimination—a case where a church was denied a benefit simply for being a church.

Back in 2012, the Trinity Lutheran Child Learning Center applied for a Missouri program that helped fund playground resurfacing using recycled tires, but was ultimately excluded because of its religious affiliation. (Days before Wednesday’s arguments, Missouri’s new governor amended what he called a “prejudiced policy” to now include religious organizations in the program.)

The Missouri constitution doesn’t allow state money to go “directly or indirectly, in aid of any church, sect, or denomination of religion.” More than 30 other states have similar restrictions, which go beyond the First Amendment guidelines on religious freedom to address government funding in particular.

Such laws, nicknamed “Blaine Amendments,” regularly come up in church-state debates. Cortman said that a victory in the Trinity Lutheran case won’t strike down the state-level Blaine Amendments, though it could set a precedent against a strict interpretation of the funding ban.

The Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty (which is not affiliated with the SBC, but with more than a dozen other Baptist groups) has argued against Trinity Lutheran. Its friend-of-the-court brief defends the church-state separation Missouri upheld in its decision.

“Restrictions on aid to religious institutions are not suspect, but they are an effective means to protect religious liberty and the separation of church and state,” said Holly Hollman, general counsel of the Baptist Joint Committee.

“Although our constitutional tradition allows for limited government funding for some activities of religiously affiliated nonprofits, churches are treated differently, and that’s good for churches,” she said. “All houses of worship receive special legal status to protect their autonomy and religious liberty.”

Evangelical organizations—like other religious nonprofits—have good reason to avoid aid that may conflict with their values and identity or lead to dependency, according to Thomas C. Berg, a law professor at University of St. Thomas in Minnesota. But there are other factors at play.

“When religious organizations have to compete on an unlevel playing field, because their nonreligious competition is receiving aid, that affects their autonomy as well,” Berg said. “As a general matter, in a time of active government—where either providing aid or withholding it can affect religious organizations’ autonomy—I think the presumptive legal rule should be to treat those organizations as eligible for even-handed aid and let them decide whether applying for it will advance or hurt their autonomy.”

Gorsuch has been known to favor free exercise, so his vote could sway a split court in Trinity Lutheran’s favor.

“His jurisprudence demonstrates an even-handed application of the principle that religious liberty is fundamental to freedom and to human dignity,” stated Hannah Smith, senior counsel for Becket (formerly the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty). “And that protecting the religious rights of others — even the rights of those with whom we may disagree — ultimately leads to greater protections for all of our rights.”

The firm has also filed on Trinity Lutheran’s behalf and sees ample legal backing for a victory: “A long line of Supreme Court cases says that the government can’t ban religious people from getting public benefits simply because they are religious. And a long line of Supreme Court Justices has decried the history of state Blaine Amendments as ugly, anti-Catholic bigotry.”

Voters in states like Missouri and Oklahoma have rejected proposals to do away with their versions of such amendments, named for a 19th-century congressman, James G. Blaine, who proposed a failed Constitutional amendment aimed at keeping tax dollars out of sectarian schools.

“State lawmakers have attempted to introduce constitutional amendments that would repeal Missouri’s Blaine provision, but they haven’t been successful,” the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported. “The issue could resurface this legislative session, as lawmakers and Gov. Eric Greitens have expressed a willingness to consider school choice proposals, such as vouchers for students to attend private school.”