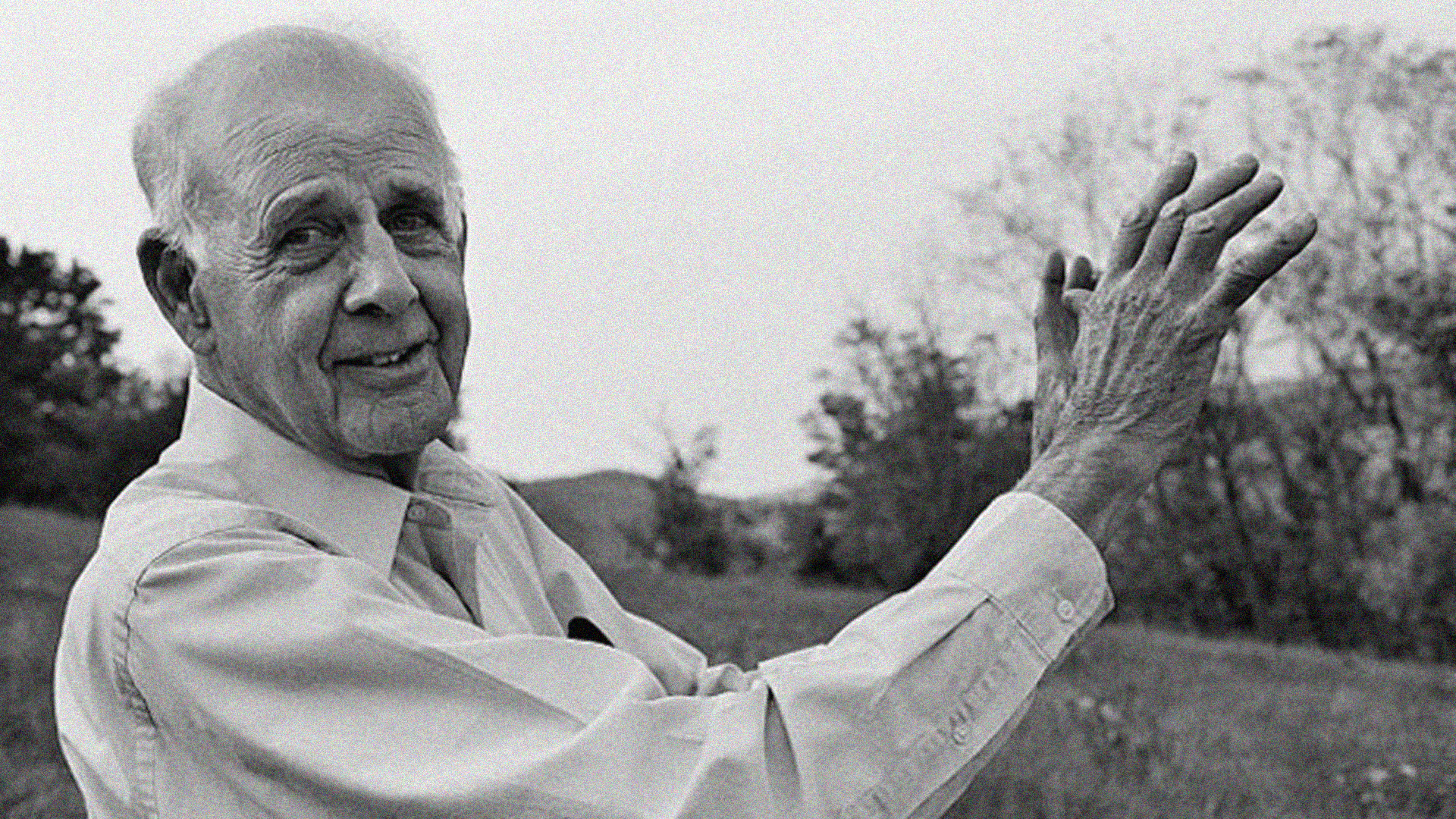

Wendell Berry’s body of writing—spanning over 50 books of poetry, essays, novels, and short stories—can be rather overwhelming to those who’ve merely seen his name on the wall of a farmers’ market or the menu of a hipster cafe. Too many Christians still have only a vague sense of who he is or why he is important, and Ragan Sutterfield’s book, Wendell Berry and the Given Life, prepares readers to explore Berry’s work for themselves.

Sutterfield is well-suited for this task. He is ordained in the Episcopal Church, a former small-scale farmer, and the author of several books, including This Is My Body: From Obesity to Ironman, My Journey into the True Meaning of Flesh, Spirit, and Deeper Faith (2015).

Berry has been an important voice for the last 40 years, but I can see at least two reasons why we should particularly heed his wisdom now. The first is the election of Donald Trump, which many have interpreted as rural America rejecting the country’s reigning economic and political orthodoxies. Berry has spent decades criticizing the industrial assumptions that shape the policies of both major parties, but the local, humane, sustainable economies for which he advocates could not be more different from Trump’s bigger-is-better rhetoric. As Bill McKibben writes in the foreword to Sutterfield’s book, “if there were a literal opposite to Donald Trump on the planet, it would be Wendell Berry.” Perhaps this is the moment to listen carefully to Berry’s vision for creaturely economies.

Sutterfield’s introduction to Berry is also timely given the conversations sparked by Rod Dreher’s new book, The Benedict Option. (It was Dreher, after all, who in a 2011 essay nominated Berry as the “Latter-Day St. Benedict” hoped for by Alasdair MacIntyre in the famous closing paragraph of After Virtue.) While Sutterfield doesn’t mention Dreher’s project, he argues that, like Benedict, Berry provides a “coherent vision for the lived moral and spiritual life. … His insight flows from a life and practices, and so it is a vision that can be practiced and lived.”

While some critics accuse Dreher of advocating withdrawal from secular society out of a fear of contamination, Berry offers a clear alternative to this misconception. For Berry, the real danger is not contamination but complicity; as he notes in an interview with Sutterfield, all who care for the health of the land and its human communities are “involved inescapably in … wrongs that they oppose.” Thus he advocates practices and reforms that reduce our participation in such wrongs. His work reminds us, then, that our faith must be embodied, that it must go to work in local, loving economies that strive to honor the immeasurable gift of life.

Humble, Loving Communities

Like Berry’s own writings, Sutterfield’s book follows a symphonic structure: Throughout its 12 brief chapters, themes emerge, develop in new contexts, and find creative resolution. It is perhaps helpful to understand Sutterfield’s exploration of a given, creaturely life as having four main movements. The first considers Berry’s understanding of coherent, loving communities. Berry always works as an amateur—in its etymological sense of lover—whether he is tending his small Kentucky farm or writing poems, essays, and fiction. In all its varied forms, his work models the humility and love that characterize neighborly economies.

As finite creatures, we are always acting from a place of inescapable ignorance. Too often, Americans arrogantly seek to overcome this ignorance, but Berry proposes instead that we limit the scale of our actions and endeavors to fit our work into the fundamental patterns of creation. Such proper humility enables authentic love. Because love cannot be abstract, we can never love globally but must, like the Good Samaritan, tend our wounded neighbor.

Berry’s commitment to humble, loving communities leads into Sutterfield’s development of his economics. For Berry, healthy economies must begin with the household, which is, after all, what the original Greek term oikos denotes. The industrial economy outsources responsibility to various proxies—we have specialists make our food, clothing, and shelter, and other specialists care for our children, sick, and elderly. A more Christian economy, on the other hand, practices love by making our households centers of production and care so that we can responsibly tend the sources of our lives.

The Benedictine phrase ora et labora flows from this understanding of work as a loving response to God’s prior gift. On this view, our vocations—the work to which we have been called—represent one of the ways we give of ourselves in imitation of the one who has given all. Sutterfield makes this point by way of a lovely midrash on the Lord’s Prayer: “When we come to truly understand our givenness, which is also our indebtedness and embeddedness in the whole of the creation, then our response must be to give as we have been given, even fore-give as we have been fore-given.” Indeed, if all life is ultimately a gift, then our primary response to it should be not work, but grateful rest, which is why Berry emphasizes our need to practice the Sabbath. In Berry’s case, this rest opens space for hospitality: On Sundays he welcomes both the muse that inspires his Sabbath poems and the visitors who come to spend the afternoon on his front porch.

The third movement of Sutterfield’s book imagines how our households might be joined to others in embodied, rooted memberships. While talk of community can sound exclusionary, Berry’s sense of membership is radically inclusive. As one of his fictional characters, Burley Coulter, famously puts it, “The way we are, we are members of each other. All of us. Everything. The difference ain’t in who is a member and who is not, but in who knows it and who don’t.” In reflecting on Paul’s metaphor of the church as Christ’s body, Sutterfield writes, “This unity is made not through the purity of identity, but in a kind of coherent relationality, a wholeness. It is in such a membership that our lives are made complete by being brought into communion with others.”

This kind of deep communion is threatened both by the restless mobility that characterizes Americans and by consumerism’s penchant for turning distinctive places into interchangeable anyplaces, where every Starbucks feels like every other Starbucks. Berry’s prescription for our transient, displaced culture is to stop somewhere and begin knitting ourselves into the warp and woof of our particular places. As Sutterfield puts it, “The challenge for us is to embed and entangle ourselves in one another’s lives and the life of our places so that both our neighborhoods and neighbors matter.”

Imagining an Alternative Kingdom

This is not an easy task for those of us reared in a consumerist culture. In the final chapters of his book, Sutterfield wrestles with this hard edge that, he suggests, makes Berry one of our contemporary prophets. In particular, Berry’s commitment to tell the truth and to practice peaceableness are unfashionable, yet they are central to his efforts to resist the abstracting forces of an industrial economy. Like the biblical prophets, he laments contemporary injustices so that “we can begin the new work of imagining and embodying [an] alternative kingdom.”

In our time of political and culture turmoil, the deck remains stacked against caring, creaturely economies. Sutterfield’s book offers hope, however, by helping us hear Berry’s call to shape our households in ways that would honor the precious gift of life. As he concludes, “When the prophet calls, there are always some who will answer.”

In the book’s afterword, Sutterfield transcribes his recent interview with Berry. When he asks Berry what “continues to give you hope,” Berry replies, “I am sustained by what I know of the history and present examples of good work, and by the goodness and beauty that I still find in the world.” As Sutterfield so ably demonstrates, Berry’s life and writing offer shining examples of such good work. They faithfully bear witness to the immeasurable goodness of our given life, and they challenge us to begin practicing the creaturely virtues of humility and love, work and Sabbath, membership and stability, honesty and peaceableness.

Jeffrey Bilbro teaches English at Spring Arbor University in Spring Arbor, Michigan. He is the co-author of Wendell Berry and Higher Education: Cultivating Virtues of Place (University of Kentucky Press), which releases in June.