[Our job as Christians is] to have constantly before our eyes in the room we most frequent some work of the best attainable art. This will teach us to refuse evil and choose the good. – George MacDonald

Now is the time to loosen, cast away The useless weight of everything but love. – Malcolm Guite

I both love and dread Lent.

I dread it because it asks a great deal of me. It invites me to give up things that I enjoy, things whose absence I might feel acutely, in some cases painfully. It does so not, as the casual Christian might suppose, as a way to inconvenience me or, more brightly, to enable me to live a more healthy, fruitful, faithful life (which, here and there, it does, and thank God for that).

Lent is decidedly uninterested in such pragmatic outcomes. It is interested instead in helping us to die a good death, with Jesus and with others who have bound themselves to the One whose death defines all deaths and defies death itself, and whose resurrected life determines the shape of the life that is truly life.

Each year, around the latter part of winter, Lent arrives. It nearly always surprises me. Here it is, once again, summoning me to change how I typically live. Predictably, I dread this summons every time. If there were an option to tack on a few extra days to the “ordinary time” that follows Christmastide, to forestall the arrival of Ash Wednesday, I would take it in a heartbeat.

For ten months out of the year, excepting the “little Lent” of Advent, I go about my life ordered by a range of habits, governing how I eat, drink, sleep, talk on the phone, check email, exercise, write books, make decisions, treat other people, mow the lawn, pay bills, pray, worry, and worship.

For the 40 days of Lent, I am invited—and, yes, it is always an invitation, never a coercion—to order aspects of my life differently, disrupting hereby my usual rhythms. This is, of course, what Lent intends to do: throw us off.

Lent is an invitation to get us outside of ourselves, so that we might get over ourselves and redirect our lives more wholly to God and to our neighbors. Lent derails our governing inertias to jolt us into seeing things that have gone unnoticed or into feeling things that have begun to calcify into self-absorbed preoccupation.

The mid-20th century Catholic theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar once observed that the work of Jesus was to remake the self by unselfing it. Christ’s work opens up a “vacant space” in us for the Spirit of God to renew us. This space, von Balthasar writes, “is occupied by Christ and his Spirit, who confirms to us that we, like the Son, are children of the Father.”

If there is no “space” in us, if we are too full of our to-do lists and projects and notifications and likes and deadlines and anxieties and obligations and wants and shoulds, then there is no room for the Spirit of God to confirm our status as beloved sons and daughters of our Father in heaven.

Left to our own devices, we will never manage to find enough time to make space for God; we will squeeze him in and hope for the best. We will make due with an honest effort here, a flurry of activity there, to deny our false self and, with Saint Paul, to crucify the flesh with its errant and erring passions, so that God might make something useful of us in the world.

Thank God we are not left to our own devices.

In fact, with Lent, as with all the feasts and fasts on the church calendar, it is quite the opposite. We are not left to our own impressions and impulses; we are instead entrusted to the wisdom and care of the church universal. We are not asked to make the most of our lives but are rather invited to frame our lives by the life of the Beloved Son, whose humanity acts as the proper orientation for all human life.

We are not left to our own spiritual meanderings, hoping for the best, whether a survival tactic to enable us to endure the tedium of our weeks or a ticket to give us entrance into the communion of the spiritual elite. We are invited, rather, on a 40-day pilgrimage, alongside other pilgrims, much like ourselves and sometimes decidedly unlike ourselves, in memory of the ragtag people of God who, in their great Exodus, wandered the desert for 40 years.

For if there is one thing that the church as Christ’s body would remind us of over and over, it is this: We cannot do it alone. We cannot wander with Christ in the wilderness by ourselves. We can only do it with others, who by faith and in sore need of the same divine grace, seek to walk in the way of Jesus.

Because Lent is an annual pilgrimage, it is all about repetition, the opposite of reinvention.

When I visited the doctor at age nine, he told me that my feet were too flat. If I did nothing about it now, it would hurt me as an adult. So the doctor prescribed a series of exercises. Every morning, before going off to school, I stood up against the wall and lifted up on the balls of my feet, then lowered down slowly, up and down. I did this 100 times in a row. In time, my arches were strengthened. It was repetitious, unexciting work, but much like the work that I have done as an adult with a counselor, a therapist of the soul, it was well worth it.

This, it seems to me, is what Lent is after: 40 days of exercises, repeated year after year, in the company of pilgrims, whose aim is to be conformed to the life of Jesus so that we might be made whole. Inasmuch as Jesus came to heal the world which God so loves, he does so by his Spirit in care-full, deliberate, systematic and systemic ways, very much like the work of any good therapist. The Spirit heals us by mortifying all that is bent against God in us and by making us hale and holy, so that we might become agents of Christ’s life in the world..

This is what I love about Lent.

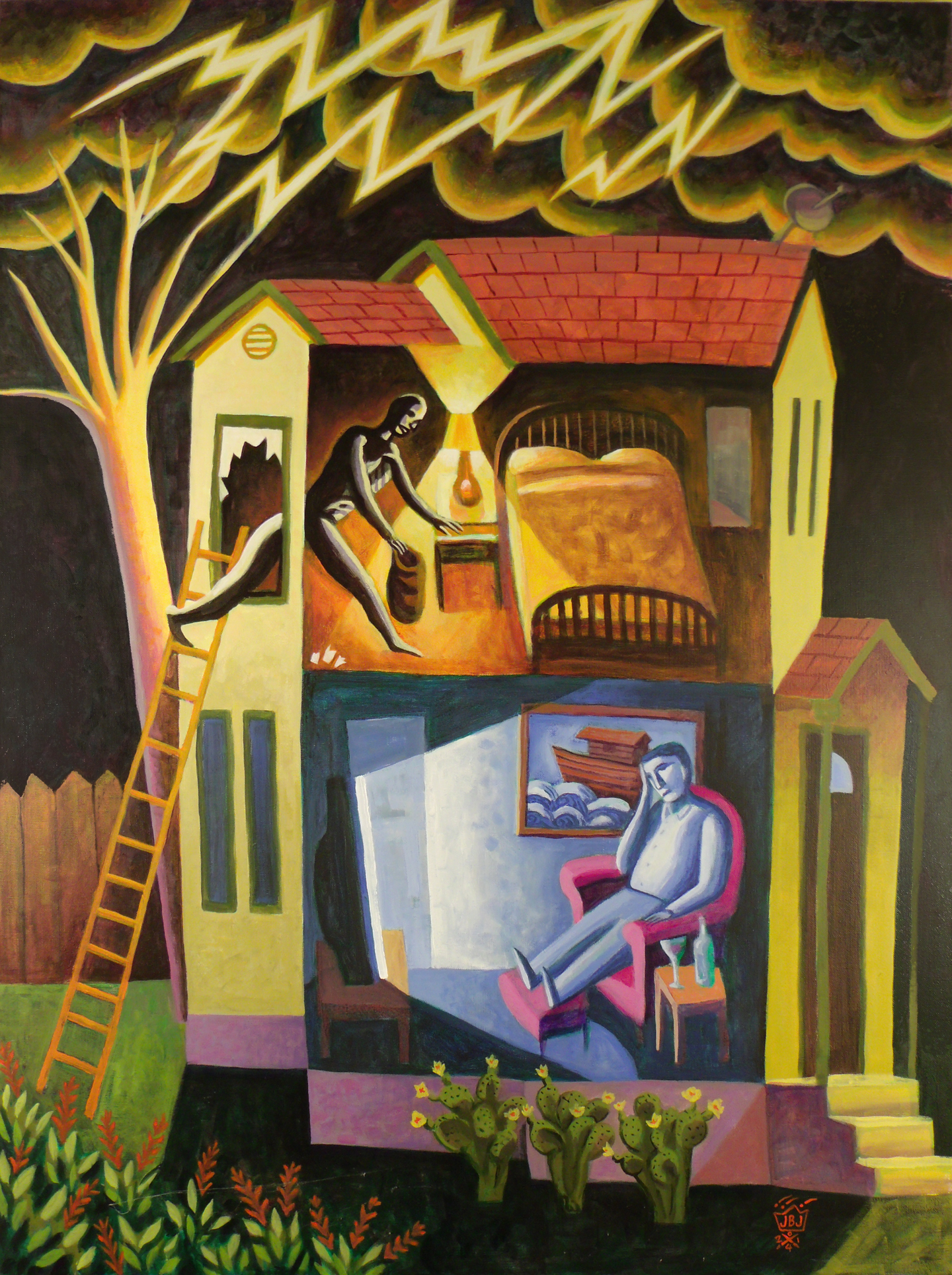

And while it is true that Lent is not interested in reinvention, it certainly welcomes all forms of reimagination. This is the great gift of artists like Jim Janknegt, for example. They help us imagine our participation in the fellowship of Christ’s sufferings. (Janknegt is the author of a new book of Lenten Meditations, which includes 40 paintings based on the parables of Jesus, one for each day of Lent.)

They fix before us an image of a world broken by our own doing, but not abandoned by God. They question our habits of sight. They arrest our attention.

See this image. See it for the first time, again. See what has become hidden and distorted. See the neglected things. See the small but good things. It is in this way that artists can rescue us from what the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge calls the “film of familiarity” and the “lethargy of custom.”

In the company of visual artists, like Jim Janknegt, we are invited to “pray with the eyes” and thereby to see the world as God sees it—a world of beauty and of terror, broken yet full of hope.

In this season of Lent, with its rhythms of Scripture and prayer, community and service, my prayer is that art like Janknegt’s might enable our sight to be healed by God, as together we die with Christ, that we might live with Christ, for the sake of a more radiant, winsome witness in the world.

David Taylor is professor of theology at Fuller Theological Seminary and the author of The Theater of God's Glory: Calvin, Creation, and the Liturgical Arts (Eerdmans: 2017). Janknegt’s book is of artwork, meditations, and prayers is called Lenten Meditations.