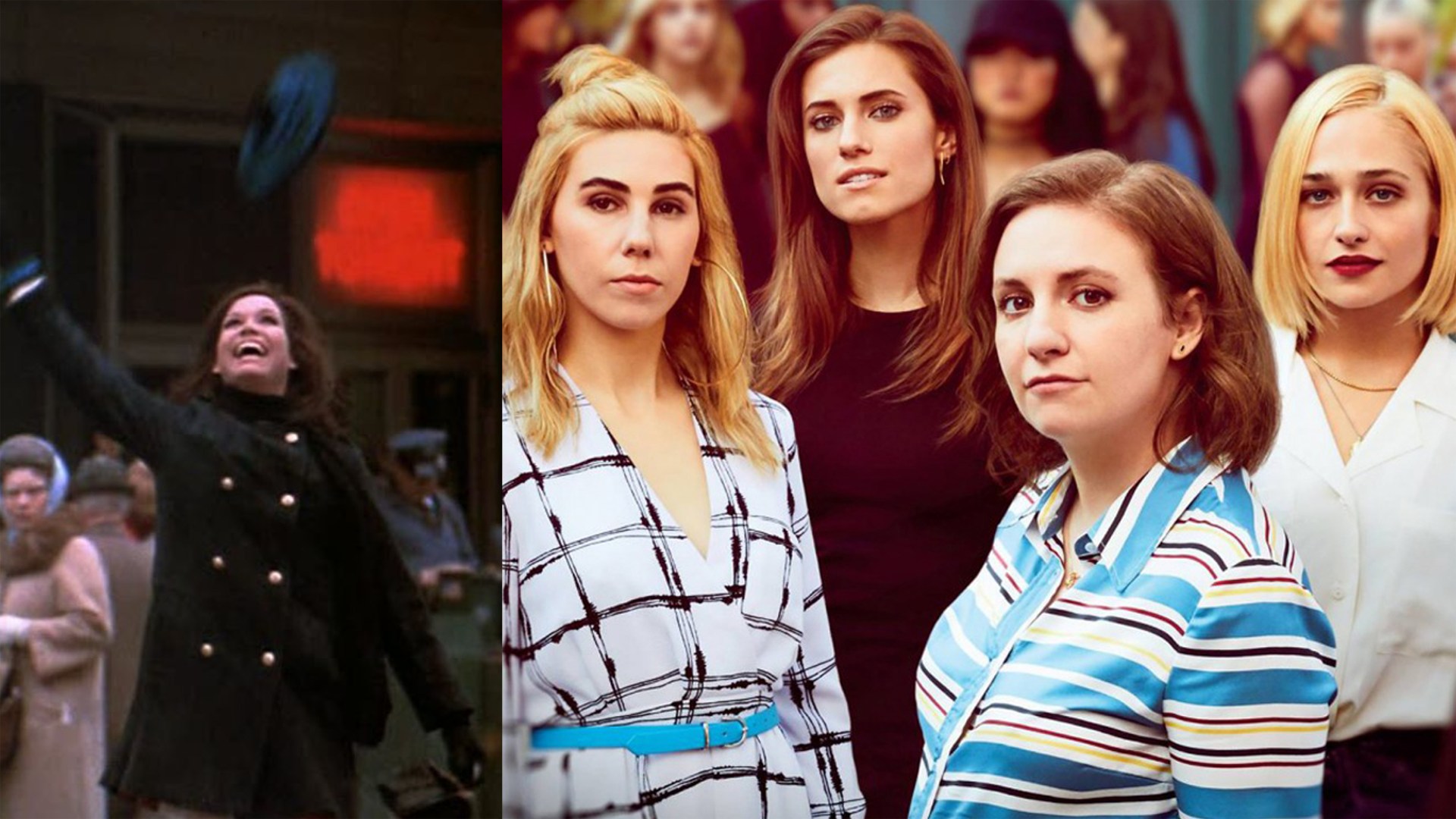

Female television fans are saying some hard goodbyes this month. Two weeks ago television icon Mary Tyler Moore passed away at age 80. This Sunday, Lena Dunham’s HBO series Girls will debut the first episode of its final season.

Separated as they were by years and their approaches to, well, just about everything, it is easier to imagine these two actresses as poles on a spectrum from “purposefully disturbing” to “calculatingly genial” rather than as co-laborers for a common cause. And yet it’s hard to name any two women who have influenced the way television portrays single women more than Dunham and Moore.

As creator, writer, and star of Girls, Dunham has represented the unique challenges of millennial women—from reconciling high hopes in a crappy economy to understanding one’s relationship status in a hook-up culture.

Over the life of the show, Dunham has exploited HBO’s reliance on nudity for her own ends and in so doing served up a feminist critique of unrealistic images of women’s bodies. In a recent interview, Dunham recalled how her insistence on frequent nudity almost spoiled her effort to recruit series regular Allison Williams: “She said, ‘I don't want to do nudity.’ I was like, ‘We have to get back to you. I'm gonna be naked, people are gonna be naked—that's a big part of what this show is.’” The sexually explicit encounters on the show, however, strike me more as gritty renderings of broken dating culture than the refreshingly realistic explorations of sexuality that Dunham no doubt intended.

For all Dunham’s boundary-pushing on pay cable, it is unlikely that her show’s confrontational aesthetic will become the norm. Girls attempts to move culture like a tug boat pulls along a ship. The vanguard series has won tons of praise from the cultural elite but can only claim between less than one million and five million viewers an episode. Girls has influenced the influencers, but its niche popularity suggests that it’s no barometer for whether Americans are ready to recalibrate gender norms.

Mary Tyler Moore, on the other hand, seems to have been more deft at knowing how to nudge the machinery of culture-making in a women-centered direction. Her cheerful ’70s sitcom is widely acknowledged as a crucial pivot in our culture’s acceptance of both single and working women. From 1970–1977, The Mary Tyler Moore Show won 29 Emmys and was consistently rated in the top 20, if not the top 10 programs on television.

The Mary Tyler Moore Show debuted in 1970 with a simple but totally novel premise: It featured a single, working woman as its main character. Mary Richards is a 30-year-old journalist who moves to Minneapolis for her career. She doesn’t live with or near any of her family, nor is she hoping to find a husband and start a family of her own. Instead she forms deep, supportive relationships with other women and her work colleagues. The show de-centers men or motherhood as the central sources of identity, conflict, or comedy for Moore’s character. In fact, Richards does not date much at all—a decision (by the writers) that closed down any need to comment on the ongoing sexual revolution.

By generally ignoring its main character’s love life, Mary Tyler Moore’s series produced seven years of episodes that all pass the Bechdel test (which requires that a story have two female characters who speak to each other about something other than men). Forty years since the show aired, it’s difficult to name another actress whose body of work comes close to providing such consistently well-rounded representations of women. And yet, most of the time, the single, working woman at its center wasn’t debating feminist politics or fighting for professional respect. She was busy being the change she wanted others to get used to seeing in the world.

Therein lies the first lesson of Mary Tyler Moore: she created an incredibly likeable character who nevertheless embodied a change to the status quo. Television historian Victoria Johnson has argued that The Mary Tyler Moore Show imagined a reassuringly sane middle ground after the profound cultural upheaval of the 1960s. Through Mary’s affable character, viewers could reconcile certain feminist principles with traditional American values.

However, a comparative analysis of The Mary Tyler Moore Show and Girls does more than illustrate feminism’s impact on primetime. When reading it as a story of contrasting approaches, we encounter a larger question: What tactics for shaping—or as Christians often say, “engaging”—culture have the most impact? In a moment when so little is civil in our civil discourse and polarization is the theme of each morning’s front page, a look over our collective shoulders suggests that a “culture war” footing rooted in bold confrontation (more in line with Dunham’s approach) has rarely been as effective as a patient, steady charm offensive (à la Moore).

Moore’s sturdy optimism offers a challenge to Dunham’s confrontational style. She also offers Christians a model of what being a “faithful presence” might look like, perhaps, if we decide to go be salt and light right where we are, rather than loudly confronting others with our intentions to be so.

Moore set in motion a new, lasting way of portraying women’s lives on the screen (and also off the screen) in part because she never lost her winsomeness. She challenged viewers’ cultural values and assumptions without resorting to the posture of a warrior or the preaching of a zealot.

However, Moore’s influence didn’t entirely depend on her likability. The actress also wielded behind-the-scenes influence as co-owner (with then-husband Graham Tinker) of MTM Enterprises, the production company that produced her show and many others. Even though her style was less assertive than her feminist-activist counterparts, her investment in creating an institution distinguished Moore as one of strongest forces for women’s advancement in Hollywood. In 1973, for example, 25 of the show’s 75 writers were women. By making it a priority to hire and promote women to top roles, she gave them the power to craft their own gender’s portrayal in the media.

Moore also understood that if you want to influence the direction of culture, the content of media matters, but so do the means of making it. In his book To Change the World, sociologist James Davidson Hunter identifies the lack of attention to culture-making institutions as a chief weakness in how Christians think about and attempt to influence culture. Hunter laments, “Since the 1960s, none of the movements in contemporary Christianity have been prominent in creating, contributing to, or supporting structures in the arts, humane letters, the academy, and the like.” Similarly Andy Crouch’s book Playing God argues that institutions are crucial to culture-making because they allow our influence to be stewarded, multiplied to others, and made to last over time.

By all accounts, attempts to shape culture are difficult and largely unpredictable, especially when it comes to women. The history of the single gal on TV seems to suggest that change is not necessarily won by breaking the taboos of the dominant culture. I have just enough rebel in me to feel a little disappointed by that, and my disappointment helps me sympathize with Lena Dunham and other iconoclasts—left and right—who believe that a cultural turnaround is just one well-chosen act of defiance away.

Still, I would argue that winsomeness, not antagonism, kept people tuning into the adventures of Mary Richards and acclimating to the new woman she represented. By way of the “boob tube”—its very nickname arguably an affront to feminism—Moore used her own likeability to shift how single, working women were imagined on screen so that more women off screen could flourish. As evangelicals struggle to influence a culture dominated by values and attitudes with which we disagree, this model of winsomeness reminds us that bringing the kingdom might be less like warring with the world than being humbly Christlike within it.

Laura Kenna has a PhD in American Studies and teaches on cultural criticism, film, and writing at Trinity Fellows Academy. She also blogs about popular culture at remotepossibilitiesblog.com.