Editor’s note: On February 22, 2017, the Trump administration revoked the Obama administration’s guidance that Title IX required public schools to accommodate transgender students in restrooms and lockerrooms.

What was intended as a “list of shame” for Christian colleges may instead become a badge of honor.

The US Department of Education (DOE) now publicly lists which schools have religious exemptions from portions of Title IX, the civil rights law banning sex discrimination in educational programs that receive federal funding. The lengthy list reveals that members of the Council for Christian Colleges and Universities (CCCU) are split on the strategy for safeguarding religious freedom in Christian higher education.

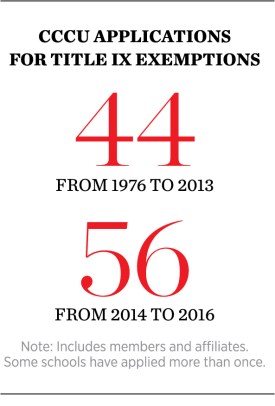

Since Congress finalized Title IX in 1975, 66 of its 246 exemptions have been given to CCCU members and affiliates. With eight more schools still on the pending list, more than half of the CCCU’s 143 American schools have claimed an exemption.

A disproportionate number of those (49%) have come in just the past three years, after the DOE sent out “Dear Colleague” letters to schools: first to inform them that they could not discriminate against transgender or gay students (2014), then to tell them that they had to treat students according to their gender identity (2016).

Dordt College, an Iowa school affiliated with the Christian Reformed Church, received its exemption this September after waiting nearly a year.

“The boundaries around religion in America are constricting to the point where I was concerned that the likelihood of the government acknowledging [Dordt] as a religious institution—and therefore being covered under the First Amendment—was decreasing,” said president Erik Hoekstra.

The protection provided by the exemption is probably broader than that of the First Amendment, said Alliance Defending Freedom attorney Greg Baylor, who helped Dordt and other CCCU schools write their letters of exemption.

“If you relied exclusively on the Constitution, you’d need to invoke it in front of the agency or judge, and it would be a much more expensive and involved argument than getting the exemption in the first place,” he said. “The outcome of it would also be less obvious.”

So far the DOE has not denied a single request (though it has stalled some for up to 10 years). It has also been willing to acknowledge religious exemptions for the first time in processing complaints. But, Baylor said, “It’s not crazy to think that might change.”

In April, under pressure from groups such as Campus Pride and the Human Rights Campaign, the DOE published a public list of schools that have asked for religious exemptions from Title IX. The list of exempt schools has sometimes been used to accuse schools of bigotry.

And the language schools have to use—asking for the ability to treat people differently because of their gender or perceived gender—can be an uncomfortable thing to do, said Erskine College spokesperson Cliff Smith.

“Personally, I think it sounds like we would like the ability to discriminate against people,” he said. “That’s one of the unfortunate parts of this whole conversation, because it really takes a direction that isn’t one any conscientious Christian would want to go.”

The list may also trigger legislative actions. This year, a California state senator proposed withholding state funds from schools that ask for religious exemptions from sexual orientation and gender identity discrimination policies.

Evangelical, Jewish, and Muslim leaders reacted strongly. Schools including Biola University and Azusa Pacific University flooded the senate committee with complaints, and students created a website explaining how the bill particularly disadvantages minority lower-income students who can’t afford to go to a private school without state grants. The Southern Baptist Convention’s Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission hammered on the same point, releasing a statement signed by 145 religious leaders that accused the legislation of being “its own form of discrimination.”

The proposal was adjusted; instead, California passed a law requiring schools to tell current and prospective students, faculty members, and employees if—and why—they have an exemption.

Fear of being on a public list isn’t enough to keep some CCCU schools off of it.

“You have to do the right thing and let the chips fall where they may,” Hoekstra said. There’s also strength in numbers, he said.

“It’s easy to dismiss one person who raises a hand,” he said. “If there is some sensitivity or pushback, it signals to the federal government that they should consult with [religious colleges] before bringing these things forward.”

Still, not all schools are choosing to ask for an exemption. Some, like Erskine, are still evaluating how to address Title IX issues.

“We want to make sure we’re clear about what our theological or moral position is,” Smith said. “But at the same time, we want policies or things we pursue to not give cause for someone to be unnecessarily offended.”

Other schools, such as Bethel University in St. Paul, Minnesota, feel protected by their tight ties to a denomination. Bethel has a close legal affiliation with Converge (formerly the Baptist General Conference).

“We don’t see a benefit in asserting that exemption at this time,” said Bethel human resources officer Cara Wald. “That doesn’t mean things couldn’t change in the future.”

Cornerstone University hasn’t asked for the exemption yet, but the nondenominational school’s board is considering the possibility.

“We would have a hard time operating according to conscience without an aspect of the exemption,” said Cornerstone Title IX coordinator Gerald Longjohn. “We can be appropriately hospitable and compassionate in working with our students, but there are aspects of the ‘Dear Colleague’ letter that will cause a tension point for us.”

The school has been forced to think carefully about how to reflect Christlike hospitality in a way that doesn’t compromise conviction. And that’s a good thing, he said.

“Perhaps the ‘shame list’ has overplayed its hand a little,” he said. “We haven’t assessed whether or not [being on the list] is a positive move for our stakeholders. But given our parents and our base, any move we make that indicates we’re doing all we can to preserve our identity as a Christian college is a good one.”

Sarah Eekhoff Zylstra is a contributing editor at CT.