Don’t worry. I won’t spoil the ending. But you need to know (if you don’t already) that something extraordinary is coming soon to a theater near you.

Before the clock strikes 2017, legendary filmmaker Martin Scorsese will deliver his passion project, a movie he’s been planning for decades. It’s based on a beloved novel by Shusaku Endo about a Portuguese missionary striving to serve persecuted Christians in Japan. And if Scorsese is true to his literary source, and brings his formidable powers to the occasion, he may well deliver one of cinema’s most excruciatingly intense films about faith.

It’s called Silence. And it corners Christians with a compelling question: Are there any circumstances under which a believer should openly apostatize? Is there any earthly authority who, if he commands a believer to publicly renounce his faith, should be obeyed?

I thought about Silence a lot this week as I revisited one of the most enduringly popular films about faith: A Man for All Seasons. How could I not? Here’s another beloved drama in which the word “silence” plays a prominent role, and in which a faithful Christian is commanded to deny Christ’s authority.

In both stories, silence is a matter of life and death. But in Endo’s narrative, the silence in question is God’s: Why will he not intervene and stop the persecution of Japanese believers? In A Man for All Seasons, silence plays a different—but equally important—role.

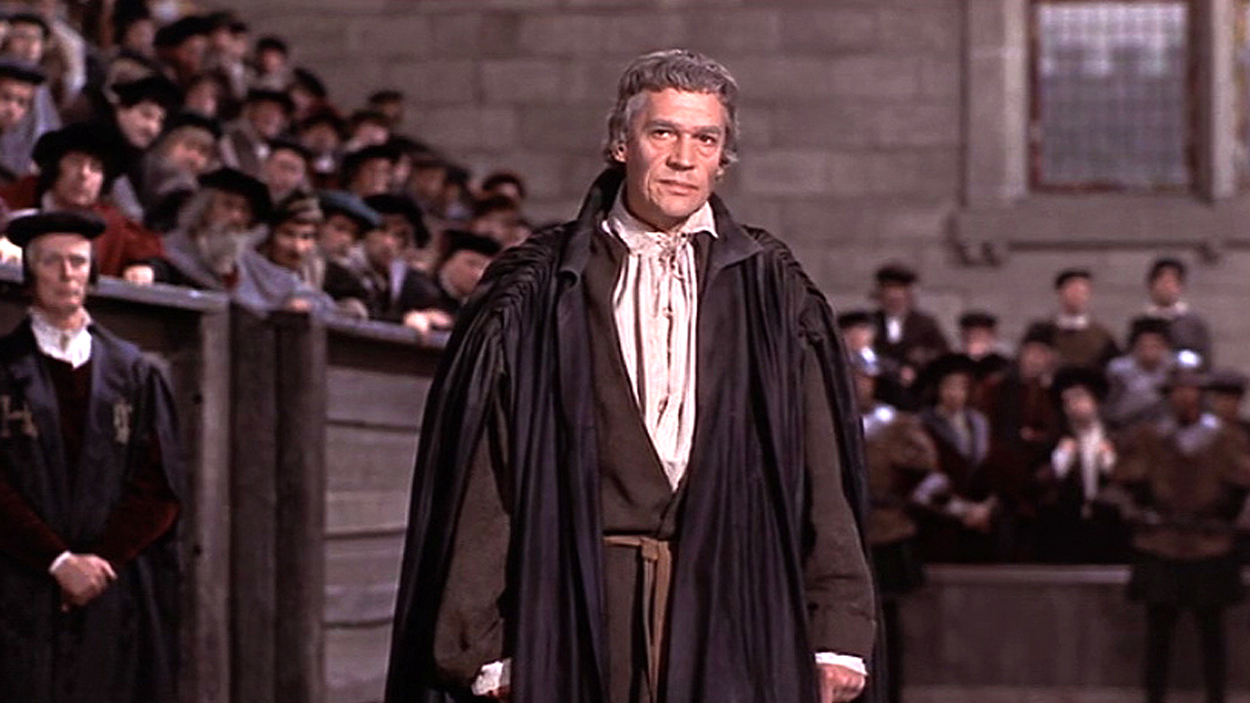

I recommend we prepare for Scorsese’s film by revisiting this classic. Directed by Fred Zinnemann from a script by Robert Bolt (adapting his own stage play), and starring the great Paul Scofield as Sir Thomas More, A Man for All Seasons puts its Christian hero to a test that recalls the climax of Endo’s narrative. More—a man as famous for his moral integrity as for his intellect—is ordered by King Henry VIII to sign an oath granting the king authority over the church. In this way, the king hopes to escape a heirless marriage to Queen Catherine and marry Anne Boleyn, maid of honour to Queen Catherine and sister of Henry’s former mistress. More’s refusal turns the world against him. England wants an heir.

So More must outwit his enemies at every turn, mastering not only his anger, but also controlling the fury of faithful friends and family, whose protests might bring deadly consequences. A genius of political strategy, he knows his only hope lies in the legal sanctuary of silence.

Every time I watch this film, I’m impressed by Scofield’s seemingly effortless performance. Who else could so seamlessly weave together More’s tender affection for his daughter, his consternation toward her brash young suitor, his inspired bursts of righteous anger, and his tremors of grief and foreboding?

He’s surrounded by a cast of giants: quite literally, in the case of Orson Welles as Cardinal Wolsey. Robert Shaw plays Henry as both hilarious and heinous, and Vanessa Redgrave is his controversial mistress. Cromwell is played by Leo McKern, who would later play a champion of justice in the BBC’s series Rumpole of the Bailey. And Richard Rich, an impetuous Judas to More’s Christ figure, is played by none other than the great Jon Hurt.

But this is Scofield’s finest hour. As he sinks his teeth into Bolt’s delicious dialogue, I defy anyone to remain unmoved. Here’s a man immune to the Devil’s seduction. His blessing won’t be bought. He won’t kiss up to a womanizing politician for his own advantage, and then feebly justify it by saying, “Hey, King David was a sinner too.”

In a crucial scene, More explains to his daughter, "When a man takes an oath, he’s holding his own self in his hands. Like water. And if he opens his fingers, then he needn’t hope to find himself again." Those are, of course, just words. But on those rare occasions when a man’s preaching is matched by his practice, he becomes luminous, and others become uncomfortably aware of their shadows. More outshines almost all big-screen characters, just as he shines in the record of history for his eloquence, his integrity, and his unforgettable silence. Would that more people like him could gain a foothold in America’s own corridors of power.

Ah, but there I go again—pinning my hopes on politicians to save the world. Perhaps it would be better to ponder: In my own daily scenarios, where are my convictions put to the test? What powers have a toxic influence over my priorities? How do I compromise for the sake of security? If Sir Thomas More had not been a prestigious Lord Chancellor of the Realm, and if he had been, oh, say, a lowly writer working as an adjunct professor…WWTMD?

I recommend A Man for All Seasons for moviegoers of all ages, although children might find More’s legal challenges difficult to understand, and the story’s conclusion frightful. It is currently available on DVD, Blu-ray, and most streaming platforms.

Questions to Discuss and Consider:

- Let’s begin by considering the matter of filmmaking artistry: Do you think A Man for All Seasons is well made? What are its greatest strengths? What are its weaknesses?

- A Man for All Seasons began as a stage play. What needs to happen for a great stage play to become a great movie? How are the art forms different? What are the differences between the challenges faced by actors on the stage and actors on the screen? Does this feel like a successful adaptation?

- Most of this movie’s energy comes from its intense conversations. There isn’t a lot of action. Do you think that imagery plays a meaningful part in the movie’s power? What images stand out to you?

- In this drama, King Henry VIII is openly unfaithful to his wife. And the Scriptures identify infidelity as a reasonable justification for divorce. Why would it have been immoral for Sir Thomas More to approve of the king’s appeal for a divorce?

- All kings, all presidential candidates—all human beings—have said and done things that are regrettable at some point. What’s a Christian voter to do? Should Christians abstain from endorsing all candidates? Is there merit in voting for “the lesser of two evils”? What governs your decisions when it comes to supporting or opposing those who govern (or who campaign in the hope of governing)?

- More’s refusal to endorse the king’s claims puts his family and friends in danger. If you were commanded to condone actions that conflict with Christ’s teaching, and you knew that refusing would endanger the lives of others, which would you find to be the braver choice—to speak the truth no matter the cost to others or to make a show of personal betrayal for the sake of others’ deliverance?

- Confession time: You may never have been forced into a life-and-death situation by a furious king, but what forces are capable of shaking your faith?

- Have you ever been in a position where you were called to stand up for the truth at risk to your reputation, your safety, or your loved ones’ security? How did you respond?

- More’s situation is complicated by the fact that he is opposed by the king, by the king’s court, and by his fellow Christians. Have you ever found yourself opposed by other Christians over a matter of conscience? How are believers called to respond when they find themselves disagreeing about God’s will?

- What lines from Robert Bolt’s script are most memorable for you? How might they speak into the challenges you face today?