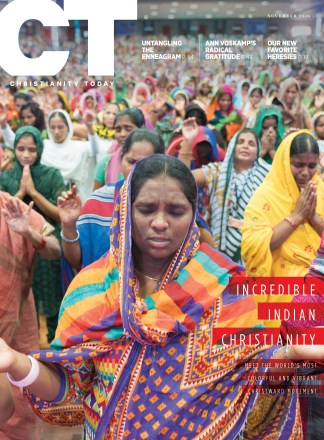

The world’s most unexpected megachurch pastor might be an illiterate, barefoot father of five.

Bhagwana Lal grows maize and raises goats on a hilltop in Rajasthan, India’s largest state, famous for its supply of marble that graces the Taj Mahal. He belongs to the tribals: the cultural group below the Dalits, whose members are literally outcasts from India’s caste system (and often called “thumb signers” because of how they vote).

Yet every Sunday, his one-room church, with cheerful blue windows and ceiling fans barely six feet off the ground, pulls in 2,000 people. His indigenous congregation draws from local farmers, whose families’ members take turns attending so that someone is tending the family’s animals. The cracks in the church’s white outer walls are a source of pride: They mark the three times the building has been expanded.

Thousands of colorful flags stream down the sanctuary along the blue beams that support the corrugated metal roof. Their rustling approaches a roar.

When asked the reason for the flags, Lal responds, “For joy!” laughing heartily. The decorations are normally used at weddings. “The same feeling should be inside the church. People should feel this is God’s place.”

Gary S. Chapman

Gary S. Chapman

Yet consider a contrasting megachurch in southern India. A taxi drives under the shadow of Hyderabad’s four-story elevated train, whose massive support beams are marked with alternating colorful gods and goddesses. The roadside, lined with movie posters and squatter tents, gives way to clusters of large stone elephant-headed gods waiting to be painted with customary bright colors. The taxi turns into a dense traffic jam: a mile-long jumble of buses, motorcycles, and pedicabs surrounded by a throng of people on foot.

Amid the chaos, one detail jumps out: Many people have Bibles in hand.

An ad above the corner bus stop reveals why: “Welcome to the largest church in India.” The crowd is departing from Calvary Temple—its 6 a.m. service, no less. The church can accommodate 35,000 people and fills each of its five Sunday services. Its Sunday school teaches 7,000 children.

Founding pastor Satish Kumar has just returned from speaking at Rick Warren’s Purpose-Driven Church Conference. He speaks between a thick fabric cross and a pulpit that replicates the facade of the church. When he asks his congregants to open their Bibles and turn to 1 Corinthians 13, the rustle of pages sounds like the rushing wind back at Lal’s church.

“Many Americans think nothing is happening among Christians in India,” says Kumar after the service. “We have to change that opinion.”

Gary S. Chapman

Gary S. Chapman

Christianity Today circled India from north to south and back again for two weeks in order to witness the innovative and successful mission efforts of Indian evangelicals—this, despite rising persecution from Hindu nationalists. In fact, evangelical leaders across India agree that their biggest challenge is not restrictions on religious freedom, but training enough pastors to disciple the surge of new believers from non-Christian backgrounds. They believe the church’s future in India is not a persecuted red (or rather, Hindu saffron) but a rosy one.

The best estimates of Indian Christians range from 25 to 60 million, with the majority being Catholics. That’s a tiny minority amid 1 billion Hindus, but still sizable enough to rank among the 25 countries with the most Christians, surpassing “Christian countries” such as Uganda and Greece.

This is why a US missions agency now trains its new cross-cultural workers in India alongside Indian counterparts. “This is real collaboration by the global church,” says P. Singh, a leading scholar at a respected Christian institution.

Addressing mixed groups gathered at eight tables flanked by flags, Singh asks the trainees to share three stereotypes about each other’s homelands. The Indian lists for Americans include: “Hollywood, burgers, Donald Trump”; “punctual, disciplined, educated”; and “rich, white, luxury of choice.” The American lists for Indians include: “Hinduism, food, Bollywood”; “rickshaws, cows, bright colors”; and “productive, crowded, mysterious.” Singh asks, “Do you mean productive in terms of population?” Everyone laughs.

But Singh has a point: It’s past time for Westerners to shed their stereotypes of majority-world Christians as poor and persecuted. When Western missionaries largely left India after independence in 1947, he says, God raised up indigenous Indian workers whose efforts are bearing more fruit than churches can harvest. “It’s the missio dei,” says Singh. “God will always find a way to bring salvation to his people.”

Gary S. Chapman

Gary S. Chapman

From Graveyard to Vineyard

Indian Christianity is hard to quantify, as one would expect in a diverse and dense nation of 1.25 billion. (This story restricts itself to evangelicals, and excludes India’s heavily Christian northeastern states.) But whether pastoring churches in the wilderness or in city centers, evangelical leaders across the subcontinent agree that God is moving like never before.

“North India was known as the graveyard of missions,” says Isaac Shaw, president of Delhi Bible Institute (DBI). “It was the heartbreak of evangelism.” Now these descriptions feel as dated as colonialism.

While Christianity previously flourished primarily in South India, today the clear trend is robust growth in the North. For example, in the 1980s, DBI discipled and sent out 100 students per year to pastor in the North. By the turn of the century, it was sending 1,000. Last year it sent out 7,600 students. Its goal for 2016 is 10,000—and it’s achievable, says Shaw. “You can see how the leaven of God’s truth rises slowly but surely.”

India’s reputation as a missionary graveyard is now as outdated as colonialism.

Standing next to the prominent cross on the roof of a seminary, president F. Philip surveys a lake in Rajasthan near a vacation spot that some consider India’s most romantic city. But the school is located here for another reason: India’s “tribal belt” is fast becoming its “Bible belt,” with church planting and baptisms surging in the states that bifurcate the subcontinent from Gujarat in the west to Jharkhand in the east.

Many US evangelicals will recall the earlier event of the Dalits’ possible move toward Christianity around the turn of the millennium [see “India Undaunted,” CT May 2004]. But today, more evangelistic energy is being focused on India’s tribals, according to Philip, regional director for the Lausanne Movement and editor of Christian Trends, an Indian evangelical magazine.

“There has been a tremendous response to the gospel among the tribals,” says Philip. The resulting challenge is having enough trained leaders, given that most tribals are very poor and minimally educated. The seminary trains tribal pastors to serve a network of 300,000 believers worshiping across 1,600 congregations. Most of the school’s 140 current students are first-generation Christians. “Our desire is to take the least,” says Philip, “and make them the best.”

Gary S. Chapman

Gary S. Chapman

But Christianity is not growing only at the bottom of the caste system. Leaders report encouraging growth among Indians from all types of non-Christian backgrounds.

At Singh’s institution, faculty offices are labeled not by professor names but by significant places in international church history: Ephesus, Chalcedon, Wittenberg, Edinburgh. Most Western Christians wouldn’t recognize the city on Singh’s door. Dornakal is where the first Indian Anglican bishop, Vedanayagam Samuel Azariah, served for decades and the church grew from 50,000 to 250,000.

In the adjoining office, labeled “Lausanne,” the four staff members of the Research Project on Christward Movements are analyzing five new groups of people turning to Christ across India’s socio-religious spectrum. They already have 2,500 pages of interviews with new believers.

Gary S. Chapman

Gary S. Chapman

Surviving the Saffron Surge

In Varanasi, the walls of a call center display posters encouraging workers to “think positive” and listing “15 mantras for how to live better.” One poster stands out. Its text comes from John 16:33: “In the world you will have tribulation; but be of good cheer, I have overcome the world.”

The center is actually a “prayer tower” hotline run by Living Rock Church, whose seven volunteers take about 300 calls per day. “Here in India, people pray for anything,” says pastor Patsy David. “If the cow is sick, they will call.” Many calls are for health or money problems; some, for a love interest’s change of heart. The volunteers pray with callers for 5 to 10 minutes, then try to connect them to a local church.

Doing so has never been easier. In Varanasi—where devout Hindus pilgrimage to bathe in the Ganges River—churches have multiplied from 5 in the 1990s to 250 today, says David. “Now in every nook and corner, you can find a church.”

“Where two or three are gathered, the policeman is there long before Jesus is.” – John Dayal

Perhaps because of that, more and more calls are about persecution. David shows CT a list of incidents that took place in Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state, in the past month. In one, a pastor was publically humiliated by being half-shaven, put on a donkey, and adorned with a garland of shoes instead of the customary flowers. In another, a 75-year-old pastor was beaten. Waiting in David’s office is Jogindar, a 30-year-old pastor who says he was tied upside down to a tree, beaten with sticks, and thrown into a pit. David’s list totals 26 incidents. “And that’s just the major ones,” he says. As CT leaves Varanasi, 100 pastors gather at a nearby church to discuss how best to respond.

Their main ally is the Evangelical Fellowship of India (EFI), which represents 65,000 churches across 90 denominations. (By comparison, the National Association of Evangelicals represents 45,000 churches in almost 40 denominations.) While Christian persecution in India stretches back to the martyrdom of Thomas in A.D. 72, EFI has been busy documenting today’s “saffron surge.” From independence in 1947 until 1996, EFI and its partners recorded only 39 incidents of persecution. Now, its network verifies 100 to 200 each year.

Last year, EFI and other concerned groups launched a free 24-hour hotline for Christians to report persecution. The line initially collapsed from overload. By the end of 12 months, it had received more than 11,000 calls. “Not a day goes by without a pastor being beaten up, a church being attacked, or a Christian home being robbed,” says Vijayesh Lal, EFI’s general secretary. By the end of June, his researchers had already confirmed 135 incidents—almost the same total as in previous full years.

Gary S. Chapman

Gary S. ChapmanThe perpetrators tend to be extremist followers of Hindutva, a nationalist and hegemonic strain of political Hinduism. Hindutva can be as violent as radical Islam, says John Dayal, an outspoken Catholic intellectual and activist who formerly led the All India Christian Council. High above Delhi on a club rooftop, he explains the “growing empathy between Hinduism as a religion and Hindutva as a political nationalism.”

Dayal cites the violent disruption of private meetings inside Christian homes. “Where two or three are gathered, the policeman is there long before Jesus is.”

“The government will say it’s only 1 percent causing problems,” says Dayal. “But 1 percent of 1 billion Hindus is 10 million lunatics.”

Of greater concern to Dayal and other Christian leaders are the increasing economic and political restrictions on Christians. As one leader puts it: “Instead of cutting off heads, they are cutting off the roots. They go in with the rulebook.”

For example, Dayal notes that three hills in the state of Andhra Pradesh are considered to belong to a Hindu deity, which local farmers have long “leased” the land from. But a new law says Christian farmers can no longer do so and must give up their land.

“This economic and political emasculation of Christians is the bigger problem, because you are impacting generations. You are taking away the future,” says Dayal. “You are making it punitive to be a Christian. This outweighs the violence, rape, and other opposition.”

One source of encouragement is the Catholic grave of Thomas in Chennai, because it shows that the first Christian in India was also persecuted, says Singh. It also refutes the Hindutva argument that Christians in India are just a product of Western colonialism, allowing Christians to demonstrate that their presence dates from the days of Jesus—who was, after all, an Easterner. “It shows that Christianity in India is more apostolic than colonial,” he says.

Gary S. Chapman

Gary S. Chapman

The Saffron Shadow’s Silver Lining

Some think Christians can better defend their freedoms using carrots rather than sticks. “We can’t be free of persecution, because the government has a wrong conception of what we Christians are about,” says a Christian business leader in Mumbai. “We are not anti-India. In fact, we are the only community who prays for our government and our leaders.

“The real answer is a concentrated effort as the body of Christ to appeal to and educate the government. If we are united, the Lord will be able to achieve what we need to achieve.”

“The right prayer is not for persecution to go away, but for sustenance through it.” – Paul Cornelius

Two of the best efforts so far: the National United Christian Forum and the United Christian Prayer for India (UCPI), which Lal says represent 98 percent of India’s evangelicals, Pentecostals, historic Protestants, and Catholics. Initially a prayer movement that gathered Christians in 1,500 cities in November 2013, the UCPI has convinced hundreds of pastors to pray every Sunday, plant churches, and send cross-cultural workers.

“The church is more united than ever before,” says Shaw. “Not to obliterate church lines, but to stand together against political opposition.”

Thus, many pastors see a silver lining on the saffron storm clouds. “Like the early church in Acts, persecution helps the church to grow spiritually and to expand,’ ” says Vivian Fernandes, lead pastor of Maharashtra Baptist Society (MBS) in Mumbai. “The early church was married to persecution, prison, and poverty. Now we are married to prosperity, personality, and popularity.

“What is hindering the church is not from outside—it is from inside. People can come and throw stones, then they go. But it is the people inside doing bad things that can destroy the church.”

Paul Cornelius, regional secretary for the Asia Theological Association, India chapter, agrees. “The right prayer is not for persecution to go away but for sustenance through it,” he says. “To pray for it to entirely go away is unbiblical. If the church is being the church, persecution is to be expected.

“My topmost prayer is for the integrity of the Indian church—for it to be more Christlike. The integrity of the church is where the gospel is at stake.”

Gary S. Chapman

Gary S. Chapman

Word, Works, and Wonders

Wati Longkumer, leader of the Indian Mission Association, is encouraging its 250-plus agencies to more effectively dispatch their 50,000 workers. “In light of the current situation, we should relook at our missions methods and not provoke,” he says. “We should not temper our evangelizing; instead, we should get more creative.”

Singh illustrates the spectrum of Christian mission as a wheel with three spokes. “What is the key avenue for communicating the gospel? Evangelicals say, ‘Word,’ mainliners say, ‘Works,’ and charismatics say, ‘Wonders,’ ” he says. “All three are legitimate and needed if they point to Christ. Different contexts call for one or another, and without all three, the wheel will collapse.”

During a monsoon downpour, our auto rickshaw navigates a Mumbai slum known as “Small UP.” Just past a trash-filled stream where two children play under a bridge, the road ends at the green and white gate of a Muslim cemetery.

“You are presenting Jesus with a knife and fork, but the gospel has to be eaten with fingers here.” – R.B. Lal

We disembark and turn right, walking up 92 steps—which the monsoon has turned into a waterfall—to the local Hindu temple. Then we turn left and follow the yellow-and-red brick road until it terminates in dirt. Here sits a church, literally at the end of the slum, with nothing but a small Christian cemetery and the jungle-covered mountain stretching into the mist beyond it. The building lay dormant for seven years until the 27-year-old pastor reopened it in 2013. “Here people look at churches in a negative way—as only interested in conversions,” he says. “If we go into the community directly with the gospel, then people will oppose us.” Instead, his church builds community connections through service.

Gary S. Chapman

Gary S. Chapman

To do this, it partners with the Association for Christian Thoughtfulness (ACT), which helps churches distribute materials on HIV/AIDS, abuse, and other social needs to 200 houses at a time. In the 1970s, churches and ministries in Mumbai, India’s most populous and wealthy city, filled 50 pages; the latest edition of the Mumbai Christian Directory required 338. In the middle is a bookmark shaped like a watermelon slice, bearing the blessing of Genesis 1:28: “Be fruitful and multiply.”

Mumbai churches have done just that. ACT estimates that in the past decade, more than half have launched ministries to the poor, trafficked, or other groups. “Everybody is doing it,” says CEO Alita Ram. “And India looks at Mumbai as a trendsetter. Mumbai Christians are on the forefront because of prayer and the unity of pastors over time.”

She refers to the Mumbai Transformation Network (MTN), a long-running collaboration by local pastors to serve their city. Due to its success, MTN recently gathered 180 people from 34 cities who were inspired to launch networks in their own cities.

Founder Viju Abraham was motivated by India’s most famous Christian. “Why does Mother Teresa have a better message than us?” he says of the nun, recently sainted for her work with lepers. “There is something wrong with our theology if we do evangelism but no social work. If she has something to say and we don’t, let’s re-examine our theology.”

Gary S. Chapman

Gary S. Chapman

One of MTN’s core members is Fernandes’s MBS, which operates an HIV ministry, literacy programs, a daycare, and a recovery home. “The greatest tragedy is not unanswered prayer, but unoffered prayer,” Fernandes explains at an MBS center in Thurbe, one of India’s largest red-light districts. At this center, former sex workers come to earn a dignified income by making handcrafts sold through local churches. “When it comes to prayer, we have all fallen short. We can’t all contribute financially, but we can all contribute prayer.”

“The Indian church in its own right has come to understand the power of prayer,” says Shaw. “Just like in the Acts of the Apostles, they gave themselves to word and prayer, and the church grew.”

One success story of church planting is in Bihar, known as “the land of Buddha” because it is where Siddhārtha Gautama attained enlightenment and gave many of his sermons. The northern state, which borders Nepal, is also the home of Empower Believers Connections (EBC), a flourishing house church movement.

Near the terminus of one of India’s longest bridges over the Ganges, about 60 pastors from across Bihar gather in its major city, Patna, for their twice-a-year training and encouragement. Representing 33 of Bihar’s 38 districts, they sit in a semi-circle on rust-colored plastic chairs in a Catholic retreat center ringed with photos of Buddhist tourism landmarks. A portrait of Mother Teresa graces the right of the stage; a portrait of Pope Francis is on the left. Above the stage, serenely presiding over all, is a six-foot painting of Jesus mimicking the Buddha’s garb and posture.

Gary S. Chapman

Gary S. Chapman

In addition to planting churches among Buddhists and other non-Christian groups, EBC is focused on making its churches self-sustainable through small enterprises. “We believe that God provides,” says Mathai Soren, who leads the effort. “But God has given us hands and feet and the wisdom to use them.”

India has more believers than “Christian nations” like Uganda and Greece.

EBC churches are testing out a number of “Christ-centered family businesses, so the whole family can contribute while a pastor is out doing ministry.” Examples include family farms that focus not on subsistence crops like rice and corn, but on vegetables and spices, or raising poultry and goats. Some churches run private schools; one runs a youth hostel. Another runs a boisterous brass band that performs at parties and parades. One church even manufactures LCD bulbs.

“The ministry is the priority, not the business. But the business should support the ministry,” says Soren. “And opponents have less to criticize when you are doing social good.”

Gary S. Chapman

Gary S. Chapman

Back in Hyderabad, Kumar started Calvary Temple 11 years ago with 25 people; today it claims to be the second-largest church in the world (150,000 members) as well as the fastest-growing (80,000 joined in the past three years). He estimates that 70 percent of his congregation comes from non-Christian backgrounds, and 70,000 are younger than 30.

Kumar has scaled his church efficiently: Members mark their attendance by scanning key cards at each entrance kiosk, where they pick up a small white cup filled with prepackaged Communion wine. Nearby, long metal racks hold more than 100 pairs of shoes in rows eight feet high. After its third service, the church feeds lunch to about 15,000. A free health clinic sees about 1,000 patients each Sunday, while a pharmacy offers free and discounted medicines. Every member who doesn’t attend on Sunday gets a phone call asking the reason and offering prayer. And every member gets a birthday cake delivered to their doorstep.

Kumar has achieved such scale without the theological shortcuts that many megachurches in the developing world take. Calvary Temple’s tagline is “only for those who worship in spirit and truth.” He emphasizes that his church is a “Bible-based church” that does not participate in charismatic signs or prosperity theology.

“Signs and wonders may attract people to the church, but don’t keep people there,” says Kumar. “Only the pure Word of God keeps and builds people in the church.”

Kumar preaches that Sunday from the life of Solomon, noting how the king of Israel “went wrong on wisdom, wealth, and women.” His main point: “Don’t pray for more prosperity; pray for more purity.” One way he applies it personally: His church office doubles as his living room, with his bedroom on the opposite wall. His sons sleep on his office couches.

“I never criticize or condemn the other faiths,” says Kumar. “When you have so much to tell about Jesus Christ, why would you talk about other people’s faiths? If the taste of the Christ is so good, you don’t have to bind them; they will keep coming.”

Gary S. Chapman

Gary S. Chapman

A Subcontinental Savior

Richard Howell, Delhi-based leader of the Asia Evangelical Alliance, says that “word, works, and wonders” require different permutations in India than Western Christians are accustomed to. He cites a Brahmin, a member of India’s highest caste: “We have not rejected Jesus Christ; you have not presented him in a way we can understand.” Ever since the British left, Indian evangelicals have been working to change that.

One promising strategy is to present Jesus as the path to enlightenment sought by many Hindus. “If you begin with total depravity, they don’t understand,” says Howell. “But if you present the need for restoration, they understand.” Howell says both high and low castes share a primary aspiration: hope. So Indian evangelicals are tapping into Hinduism’s many “stories of hope.” For example, Christians are reinterpreting the myth of the Baliraja—the “sacrificed king”—to show that Jesus is the one Hindus have waited for.

“Christianity is not being presented as opposed to Indian culture,” says Howell. “Instead, Christianity is being presented as the fulfillment of the cultural aspirations that Indians already have.”

While Western evangelicals have grown familiar with the C1–C6 debate over “insider movements” among Muslims [see “The Hidden History of Insider Movements,” CT January 2013], in India the contextualization debate centers on “Christward movements.” “This terminology better captures what is happening,” says Singh. “People are being drawn to Christ; maybe not to Christianity or to the church as we know it, but undeniably to Christ.”

“Christward movements are culturally Hindu yet Christian in faith,” says Howell. Members read the Bible and pray openly, but they meet on Saturdays in homes, not churches, in order to avoid “the impression that Christianity is Western.” Their biggest break is not with the Western church as much as the historic church: They don’t perform baptisms.

Howell supports their abstention. He estimates that 70 percent of Christians in India are of Dalit background, and thus constrained by the Scheduled Caste welfare regulations. “They worship no god but Jesus,” he says. “But they don’t take baptism because they will lose their jobs and families, because their benefits will be taken away by the government. The church is not equipped to help them. If they take baptism, millions would be out of jobs. What would we do?” The abstention is strategic, not syncretistic, he says.

“It’s conversion of the heart that really matters,” says Howell. “You can take 10 baptisms, but if there isn’t a change of lifestyle, it doesn’t make sense.”

Howell promotes the Christward movements as examples of “fulfillment theology.” “Let us take [Hindu practices] and put them under the lordship of Christ by giving them a Christian interpretation.” He knows that many Western Christians are “nervous” to stray so far from the historical forms of Christianity. “But we need to let God control the narrative.”

Gary S. Chapman

Gary S. Chapman

Gospel with Fingers Not Forks

One of the most intriguing cases of contextualization is Yeshu Darbar, based in Allahabad at SHIATS University, whose founder invented a better plow in order to sow the gospel. Today the Royal Court of Jesus movement occupies a strategic location near the Triveni Sangam—the joining point for the Ganges and Yamuna rivers, as well as the invisible and mythic Saraswati River—where Hinduism’s famous Kumbh Mela, the world’s largest religious gathering, is regularly held. It draws up to 10 million pilgrims, who believe that bathing in the water absolves them of sins.

“We don’t have to go out and share the gospel. They come right here,” says David Phillips, assistant to SHIATS vice chancellor and Yeshu Darbar founder R. B. Lal. “We’re contextualizing the gospel in a new way. We’re doing what George Verwer and Ralph Winter had always wanted to do.”

Yeshu Darbar has such a reputation for healings, taxi drivers at the train station use its name to divert visitors.

Yeshu Darbar’s services take place on SHIATS’s former soccer field. The stage backdrop recreates a courtyard with square white posts, green vines, and blue walls evoking the sky. Red foil and silver tinsel dangle from a ceiling emblazoned with the words of Jesus: “The time has come. The kingdom of God has come near. Repent and believe the Good News!”

After the sermon, attendees line the metal railing at the front of the stage and await their turn for Lal’s laying on of hands and anointing with oil. The line quickly transforms into an exorcism line. “Oh Jesus, oh Jesus, why are you tormenting me?” screams a partially veiled woman in a teal sari. Another woman in a green sari thrashes silently before staring Lal in the eyes and saying, “Don’t tell me to come out. She is mine.” Lal slowly repeats “come out, come out, come out” until she subsides.

Lal’s services have developed a reputation for such healings. At one point, Phillips says, the taxi drivers at the Allahabad train station started putting Yeshu Darbar’s name on their vehicles because they wanted to divert its visitors in order to make money. Meanwhile, hundreds of village pastors have replicated Yeshu Darbar’s name and approach. “We have not [trademarked] our name,” says Phillips. “If the gospel is being preached, why should we be upset?”

Gary S. Chapman

Gary S. Chapman

Lal says he never intended to launch such a movement. He was an administrator and scientist who applied “the Bible into my life, every word, and it worked.” When accused of converting Hindus and Muslims, he explains that he never asks anyone to leave their current religion.

“I consider other religions as cultures. I tell them, ‘Why don’t you take Jesus Christ and make him a Hindu? Make him a Muslim. Make him a Buddhist,’ ” he says. “I’m giving them the gospel of Jesus along with Jesus. And I guarantee you, if they accept Jesus in their own setting, transformation will take place.”

Church leaders across the subcontinent will explain that most Indians consider Jesus to be a white, Western god. Lal seeks to separate his Savior from the stereotype. “Christianity trapped Jesus Christ so that the Hindus and Muslims cannot get to him,” says Lal. “We are de-Christianizing Jesus.

“You [Western Christians] are presenting Jesus with a knife and fork, but we Indians are accustomed to fingers,” he says. “The gospel has to be eaten with fingers here.”

Howell vouches for the orthodoxy of Yeshu Darbar—its members repent, take baptism, and renounce idol worship—as well as God’s blessing. “For God to start this in Allahabad, it is the laughter of God,” he says. “And of all people, he chooses a scientist.”

“All movements are messy,” says Singh. “But what’s undeniably clear is that the Spirit is active and doing something new in our time.”

Gary S. Chapman

Gary S. Chapman

Singh takes an optimistic—and, he argues, biblical—stance on Christward movements. He cites the “Barnabas principle” from Acts 11, when the Jerusalem church sent Barnabas to investigate the newly formed Gentile church in Antioch. “Barnabas probably found the form of worship and presentation of the gospel among Gentiles to be different than among Jews. But when he found evidence of God’s grace, he was glad and encouraged them. This gave him an avenue to later teach and disciple them.” Thus, Singh’s stance: If grace is present in a movement, then encourage and equip it.

In fact, some Indian experts think Western or traditional churches trying to impose their cultural form of Christianity could disrupt church growth even more than Hindutva extremism. “If we come in with a theology checklist intent on giving certificates of orthodoxy, there is a danger of these groups getting completely withdrawn and isolated,” says Singh. “They need the body of Christ.” His goal: “facilitating these groups without fracturing the unity of the church.”

He says one biblical example is John 4:30, where many Samaritans “made their way toward” Jesus, who warns the disciples against hindering them. “These people are on a journey, and taking baby steps toward Christ,” says Singh. “Don’t see them through eyes of prejudice, like the 12 disciples saw the Samaritans. Learn to see them as Jesus did.”

“We need to take risks and take Jesus to new settings,” says Howell. “Jesus is alive. He will take care of himself.”

Jeremy Weber is senior news editor at CT.

For a Bible study based on this article, visit our sister brand ChristianBibleStudies.com.”