What is there to say about Sausage Party? A surprising amount.

Columbia Pictures

Columbia PicturesIt's being touted as the first R-rated computer-animated film, and boy does it earn the rating. Innuendo, profanity, drug use, racial slurs, and graphic sex (insofar as food items can have graphic sex) are all part of the film. I don't expect many CT readers will go to see it. (I cannot repeat this strongly enough: do not bring your children.)

But like earlier efforts by Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg like This Is the End and Preacher, it's also oddly . . . theological? (Some plot spoilers ahead.)

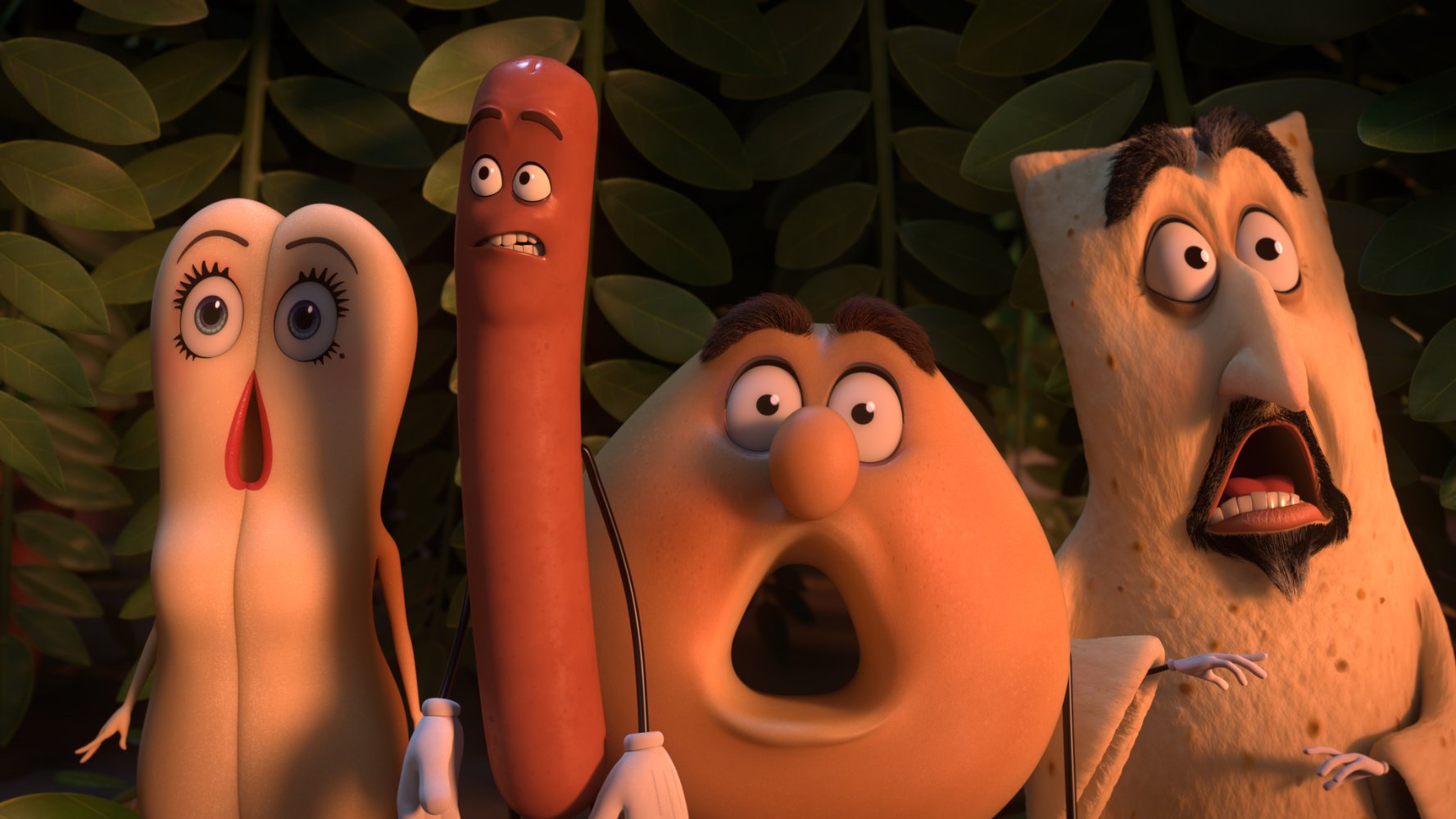

The film starts with a hymn to “the gods,” sung by the food in the supermarket as it opens in the morning. The aforementioned gods are the shoppers, by whom the food items desperately wish to be “chosen” to go to the “great beyond.” Frank, a sausage (voiced by Rogen), and his bun girlfriend Brenda (voiced by Kristen Wiig) desperately hope to be chosen together on red, white, and blue day so they can finally, uh, be together. They fool around through their packaging.

So we start with a sort of culinary Calvinism with a strong Puritan streak. But then everything goes sideways. Brenda the bun—a true believer, if there ever was one—is convinced that they are being punished by the gods for “touching tips.” The food items begin to make uncomfortable discoveries about reality, the biggest of which—no surprise to us—is that the “gods” actually have cruel designs on them and the great beyond is anything but great. It turns out the “nonperishables” (whiskey, Twinkies, and so on) made up the story of the great beyond in order to keep the food happy instead of screaming from anticipation of their impending death. Religion is the opiate of the foodstuff.

Columbia Pictures

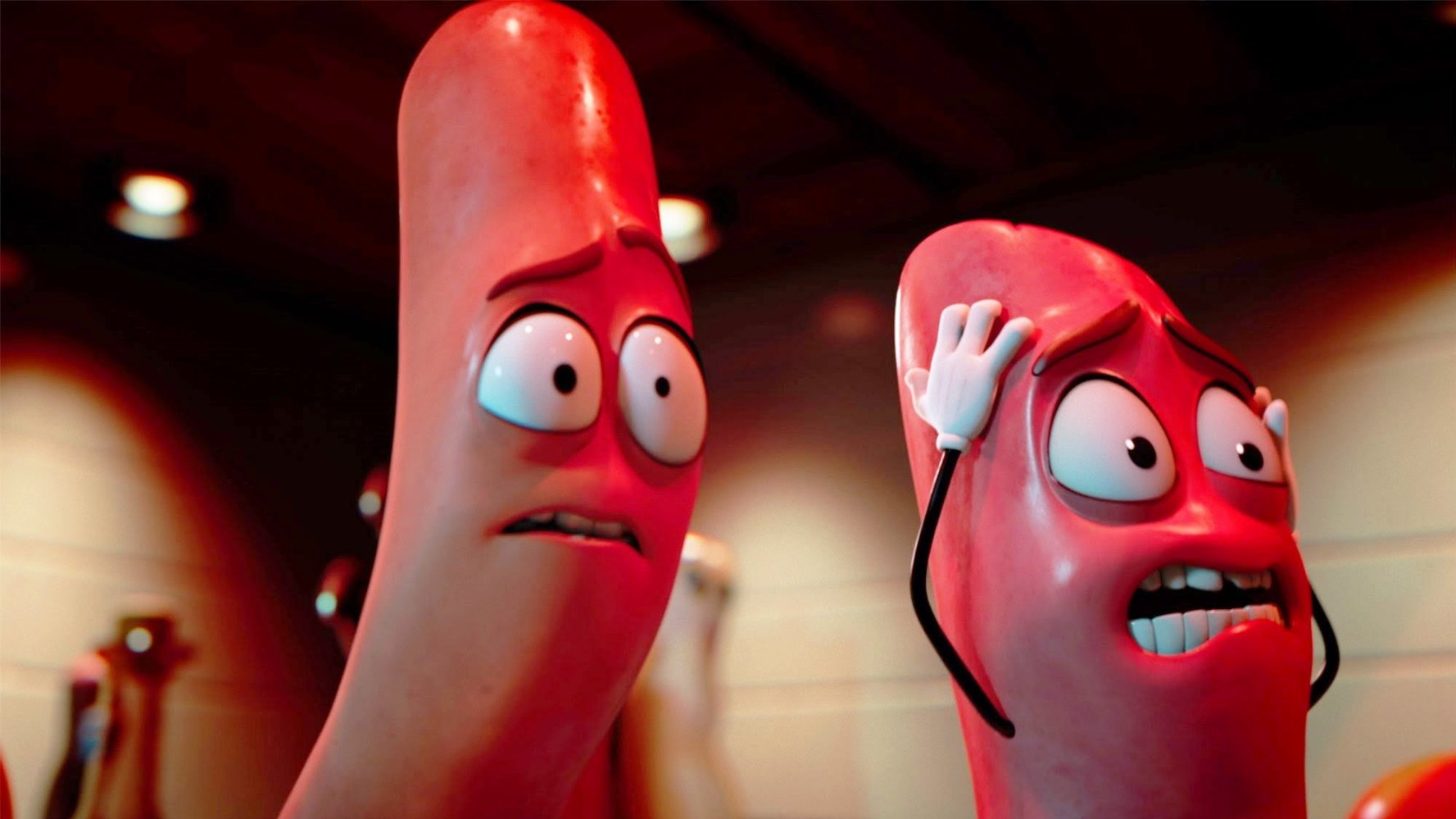

Columbia PicturesIf the movie stopped there, it would have been irritatingly dogmatic in the vein of The Invention of Lying, Ricky Gervais's humorless anti-religious screed. And certainly Sausage Party suggests an anti-theistic worldview is the most enlightened one. But as the story goes on, Frank (the hero and the lead atheist in the bunch) learns that just because you are pretty sure you've apprehended the truth doesn't give you license to cram that down the throats of those who believe (he puts it in much cruder terms). Sausage Party gives a full-throated defense of tolerance and a condemnation of ethnic and religious feuding, underlined by a subplot involving a pita and a bagel.

Sausage Party eventually has the food mounting a revolt against “the gods” and staging a sort of orgy before breaking the fourth wall with the audience. It's all very strange, but it takes seriously and even respects people’s—er, groceries’ right to believe or not, since nobody, as Frank points out, has all the answers, and if they say they do, they’re wrong.

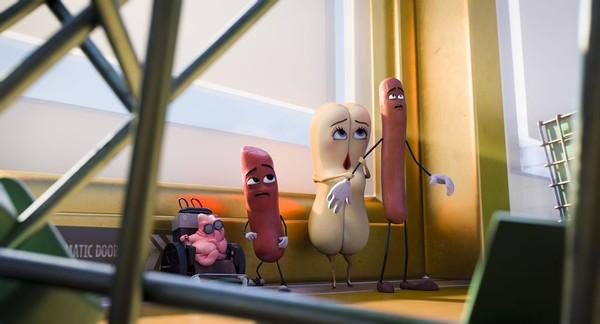

As with This Is the End, Sausage Party sees our earth as a stage en route to a greater beyond, though that looks different at the end of the film than it did at the start. But it isn't gnosticism. The films acknowledge the grossness and messiness of the material world, but they don't suggest we ought to shun it. In a classic late modern move, instead the films celebrate the dirtiness of material existence (primarily sex and drugs, but other things too) as what makes life worth living, then let their characters move into another dimension of eternal bliss. (In This Is the End, the dimension is literally heaven, and of course, the Backstreet Boys are there.) Immanence on Aisle Three.

Columbia Pictures

Columbia PicturesThere's a bifurcation in the worldview there, and, strangely, one that feels pretty familiar to some people who grew up in church. and that lines up with many Christian teenagers' truncated understanding of sexuality. But whether it's another, non-cartoon dimension, extinction, or heaven itself, we're all destined for some kind of next phase beyond this world. The film asks the audience to chill out about life here on earth, since nobody knows what happens next and, anyhow, what your neighbor wants to do isn't really any of your business.

It's a sort of anti-PC secular eschatology for a pluralist age, communitarianism for a world of individualists, and it's consistent, at least. Which, let’s be honest, is more than you expect from a film called Sausage Party.

Alissa Wilkinson is Christianity Today’s critic at large and an associate professor of English and humanities at The King’s College in New York City. She is co-author, with Robert Joustra, of How to Survive the Apocalypse: Zombies, Cylons, Faith, and Politics at the End of the World (Eerdmans). She tweets @alissamarie.