In 2008, the death of a Hindu leader led to the worst case of anti-Christian violence in India’s history.

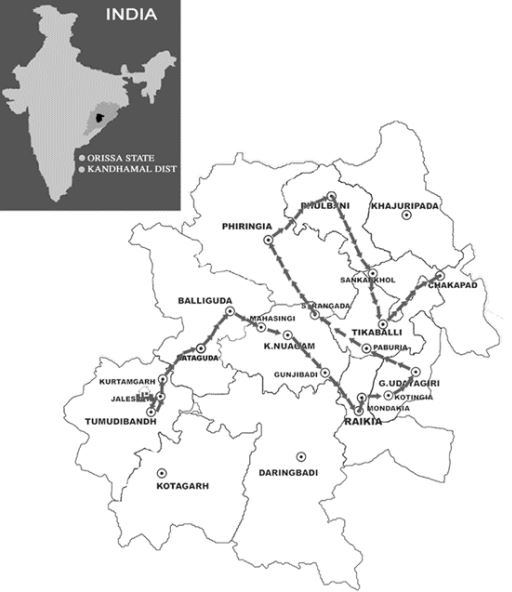

About 100 Christians were killed, 300 churches attacked, 6,000 Christian homes damaged, and 50,000 people displaced when Hindu fundamentalists blamed Christians for the murder of Hindu leader Swami Laxmanananda Saraswati. The violence took place in the Kandhamal district of the eastern coastal state of Odisha.

(The same state made the news on Christmas Eve the year before for another string of attacks connected to Saraswati, and in 1999 when Hindu radicals burned missionary Graham Staines and his two young sons to death as they slept in their Jeep. In 2008, fundamentalists announced their intention to destroy all of the Christians living there.)

This month, India’s Supreme Court ordered the Odisha government to reinvestigate the trials of perpetrators “where acquittals were not justified on facts.” Of the 827 criminal cases registered, 315 were not pursued, and in the 362 cases where a verdict was given, only 78 resulted in conviction. About 6,495 people were arrested, but just 150 cases are still ongoing.

Chief Justice Tirath Singh Thakur and Justice Uday Umesh Lalit also ruled the compensation the state government offered—from $150 to $750 for destroyed homes and about $7,500 for families who lost a member—is not enough. Odisha state had set aside about $400,000 in all to pay for the damage.

Archbishop Raphel Cheenath, who filed the lawsuit, asked for about $6,000 per damaged house and about $22,500 for each family member killed in the riots. (Cheenath, 82, passed away yesterday.)

The judges didn’t go that far, ordering an additional $4,500 for the widows and children of the 39 Christians on the government’s official death toll. They also ruled that the state and federal government pay another $300 for a home that was “partially damaged” and an extra $1,050 for a “fully damaged home.”

The court also said those who sustained minor injuries ($150) and major injuries ($450) also receive compensation.

“We do respect the judgement, but are not satisfied,” said Dibakar Parichha, a Catholic priest and advocate who has coordinated the legal fight for the Kandhamal victims. “Nevertheless, it is rather [a] good judgment for [many of] the victims of Kandhamal.”

Part of Parichha’s disappointment stemmed from the court’s decision not to increase the list of beneficiaries entitled to compensation.

“We are disappointed that Christian traders, NGOs, and others who lost their businesses to arson and violence have not been compensated,” said activist John Dayal. “The economic strength of the Christians in the district had been severely impacted in the violence—by design. But they have not been paid any compensation at all.”

“Too little, too late,” said Tehmina Arora, a Supreme Court lawyer who has played a key role in the legal challenge on behalf of the Kandhamal victims. Even the improved compensation package “does not match the amount of compensation” paid to Sikhs and Muslims after similar communal attacks, she said.

Arora acknowledged the concern expressed by the Supreme Court.

“The minorities are as much children of the soil as the majority,” she said, quoting the chief justice’s assurance as he gave his judgment. However, “this concern is not backed by a clear directive and deadline on how to address the injustice,” she said. “Who is going to monitor and follow up this directive?”

Campaigners say that India’s National Human Rights Commission has been “sitting for years” on the plea for better compensation.

For instance, despite more than 25 visits to government offices, Obseswar Nayak in Borimunda village was denied the maximum compensation of $750 for a “fully damaged house” because “part of the wall was intact.”

Another “partially damaged house”—with its first and second floor ceilings burnt—was John Pradhan’s home in Gurkapia village. Government officials also listed it as “partially damaged” since “part of the wall was intact.”

Three-quarters of the damage done to Christian homes took place along the route of Saraswati’s funeral procession, noted a website set up to protest the convictions of seven Christians for his murder. (A Maoist was also found guilty.)

“The [Hindu extremists] wanted to make a spectacle of [the body], and were prepared—as events were to prove—to take full advantage of the passions that would arise. They did not even go by the shortest route, but meandered across [Kandhamal],” noted a report by a group of human-rights organizations.

Among the slogans shouted was, “Kill Christians and destroy their institutions!”

“It was obvious that public reaction to the murder of a prominent religious leader like the Swami would be extreme,” noted the National Commission for Minorities after its September 2008 visit to Kandhamal. “Yet when options to be followed after the murder were being considered, there is little evidence that high-level political and official leadership offered guidance and support to the local district administration.”

Five years after the riots, a report by several organizations—including the former UN Special Rapporteur on adequate housing—noted that the government didn’t compensate the victims for any loss of household articles, equipment, clothing, or livestock.

The report recommended that the government “take immediate measures to adequately rehabilitate and resettle the victim-survivors of the Kandhamal violence” and “ensure full reparation to those whose livelihoods were affected due to violence and strife.”

The ruling by Chief Justice Thakur is “a step forward in justice for the victims of Kandhamal,” Sajan K. George, president of the Global Council of Indian Christians, told Fides news agency. “It is a positive sign that the Supreme Court of India recognized as unjust compensation paid. The justice procedure is slow and inadequate, but this is a sign of hope.”

After his appointment to the court in December, Thakur declared that “people of this country need not live in fear till the time the judiciary is independent. When the Constitution guarantees rule of law to those who are not our citizens, there is no question that citizens of India, no matter what religion or faith, should feel unprotected.”

Thakur’s appointment was “like a beacon of hope for those living in fear,” wrote Anto Akkara, who wrote a book about the Kandhamal events and started a petition protesting the apparent discrepancies and injustices in the case against the seven Christians who were found guilty of Saraswati’s murder.