HORATIO

O day and night, but this is wondrous strange!

HAMLET

And therefore as a stranger give it welcome.

There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio,

Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.— William Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act 1, Scene 5

The Netflix series Stranger Things revels in the strangest things conjured by pop culture: monsters, like those that spring from the twisted imagination of Guillermo del Toro (Pan's Labyrinth); government conspiracies, straight out of The X-Files; horror-thriller hybrids lifted from Stephen King; plot points that depend on Dungeons & Dragons for context.

Netflix

NetflixBy contrast, the eight-episode series' debt to Steven Spielberg, and especially 1982's E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, seems sweetly natural. Mothers and fathers, resolutely going to hell and back to save their children. Teenagers who make immature decisions, and then wise ones. Courageous children whose steadfast friendships strengthen them to face both bullies and monsters.

I was born in 1983 and didn't grow up watching popular films and TV shows, so my hook into Stranger Things had little to do with the nostalgia most people seem to experience watching the show, with its myriad references to films, TV shows, and music of the era. (I first saw E.T. in February. This February.) I was hooked purely by Stranger Things' plot, which melds monster horror, conspiracy thriller, and plain, old-fashioned suspense: Will Byers, about age 10, disappears one night, which sends his single mom Joyce (Winona Ryder, in the show's most obvious nod to the 1980s), his brother, and his friends and their families into a tailspin as they try to find him.

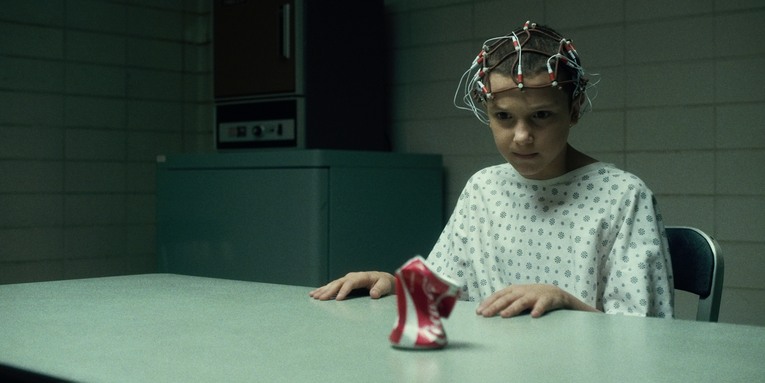

Eventually they realize something paranormal is going on—especially when the lights in his house seem to start blinking and Mike's sister Nancy's best friend goes missing. There's also a strange girl with a shaved head named Eleven who turns up, for reasons nobody can understand, and Mike and his friends Dustin and Lucas (named, I think quite obviously, for the Star Wars creator) hide her in the basement while they try to figure out how to rescue their friend. There's also the local sheriff (David Harbour), who lives a hermit's life after the loss of his own daughter, and stumbles into the story and knows he has to get involved.

Netflix

NetflixOne of the central conceits of Stranger Things is the existence of a plane of existence the boys call “The Upside Down,” a parallel dimension that exists alongside our own, but swaps out decay and death for every bit of life and flourishing on our own plane. Experienced sources (aka my husband) inform me that this, along with one of the show's major monsters, is drawn directly from Dungeons & Dragons, the role-playing game many evangelicals were warned away from in the 1990s. The show's children—its central characters (who, to the one, are fantastic)—are avid D&D players. In fact, that's how we meet them: playing a many-hours-long campaign in the basement, and unable to defeat a menacing in-game monster with their powers and rolls of the die.

Eventually it turns out that their game knowledge is applicable to real life—they take for granted that things beyond common “philosophy,” as Hamlet puts it, are there, and that instead of sitting around contemplating this mystery they ought to focus on the objective and save their friend. Joyce has a harder time convincing people that she isn't crazy to believe that Will is communicating with her through Christmas lights.

Every trope from the 1980s is here: monsters, government conspiracies, single-parent families, rebellious teenagers, bullies, the weird kid at school—even the show's title sequence and design, which seems like an obvious homage to Star Wars. And by aping the 1980s, it both taps into our nostalgia-soaked culture and blazes a new path: by switching between types of genre plots, it keeps changing the rules, keeping us from guessing (and, eventually, from knowing) what is going on in a deeply satisfying way.

Netflix

NetflixWatching Stranger Things, with its establishing shots that begin and end on the night sky, I found myself thinking of Midnight Special, Jeff Nichols' sci-fi film out this year about a young boy with magical powers and a parallel dimension that nobody can explain. Many critics (including myself) compared Midnight Special to Spielberg, citing Close Encounters of the Third Kind and E.T. as influences—as has Nichols himself in many interviews. The beauty of Midnight Special (I reviewed it from Berlin) is its suggestion of a dimension beyond what we can see, something inexplicable that refuses to conform to our rules, but nonetheless intrudes on our reality—and in this case, something explicitly religious.

That kind of parallel dimension was also the appeal of the horror novels written by Frank Peretti and sold largely to a Christian market in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Novels like This Present Darkness and Piercing the Darkness recast “spiritual warfare” as literal warfare in which Christians could engage through prayer and proclamation of Scripture. Peretti vividly evoked a demonic realm floating around our own (and perhaps accidentally triggered many sleepless nights for the teenagers reading those novels; I may speak from experience here). The idea that important things are taking place in the unseen world right around us during our boring days—that was exciting. And the idea that we might engage in those was even more exciting.

In a modern world—where science can explain everything from depression to deja vu to the Aurora Borealis, where belief and devotion are sometimes reduced to a series of steps or principles that you can execute with enough willpower—even religious folk yearn for a re-enchanted world, one where fairies, or demons, or other intelligences exist just beyond what we can see. C.S. Lewis tapped into this with the Narnia series, which posited the existence of worlds just through our cupboards and closets and re-enchanted the ideas of Scripture. Other authors have attempted it since then. Filmmakers and TV creators and painters and novelists are forever striving to re-enchant the world with their work.

Netflix

NetflixWhich, in a way, explains the popularity of Pokemon Go—a game that imbues the regular, everyday world we all inhabit with newfound mystery and surprise. Players find Pokemon hidden in the world they occupy every day. (A certain CT editor located one on a copier in our office last week, then promptly posted a photo to Facebook.) Who doesn't want to chase down presences on their block, or in their school? Who wouldn't delight in the serendipity of “capturing” a presence that isn't “really” there but might as well be?

What we're after is joy—the serendipity of discovery, the thrill of mystery, the feeling of excitement lurking around the corner. Modern science brought many great things with it, and many scientists seem to testify that they find wonder and enchantment in their work. But when this study purports to “explain” why we act as we do, or that set of principles or guidelines proclaims that if we only follow them, we'll be right with ourselves or God—well, doesn't some of the light seem to have gone out of the world?

Our desire for magic doesn't let up when we reduce the life of efficiency or of mystery to a four-step plan. But art still seems best poised to capture that magic. Stranger Things is just the latest version of this yearning—and let me tell you: it sure manages to bring joy with it.

Caveat Spectator

I think Stranger Things knows something most children's and YA entertainment of our time does not, which is that putting children and teenagers in peril does not automatically make it only appropriate for adults. However, some families may want to filter for language—the profanity used is commensurate or even mild compared with PG-rated films of the early 80s (think the Back to the Future series or Ghostbusters), which means some language of the b***h and a*****e variety. One teenage character, we understand, loses her virginity to her boyfriend; she is not punished by the show for it. Some teenage drinking (they seem to pay). But mostly it's the monsters that are frightening, plus there's some magical science-based powers displayed and science-y manipulation of children.

Alissa Wilkinson is Christianity Today’s critic at large and Associate Professor of English and Humanities at The King’s College in New York City. She is co-author, with Robert Joustra, of How to Survive the Apocalypse: Zombies, Cylons, Faith, and Politics at the End of the World. She tweets @alissamarie.