Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the best-selling 19th-century novel, rehabilitated America’s moral imagination. Author Harriet Beecher Stowe did so by humanizing a political issue. She not only gave slaveholding the villainous face of Simon Legree; she also made a Christian martyr of his slave. “If taking every drop of blood in this poor old body would save your precious soul,” Uncle Tom said, “I’d give ’em freely, as the Lord gave his for me.” The abolitionist polemic was so successful that, upon meeting Stowe amid the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln reportedly said, “So this is the little lady who made this big war.”

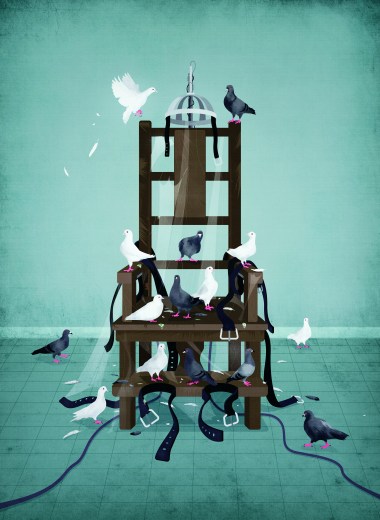

Executing Grace: How the Death Penalty Killed Jesus and Why It's Killing Us

HarperCollins

320 pages

$12.13

In Executing Grace: How the Death Penalty Killed Jesus and Why It’s Killing Us (HarperOne), Shane Claiborne takes a similar approach to argue for the end of capital punishment in the United States. Throughout the book, the activist and founder of the Simple Way tries to put a human face on the victims and perpetrators of the death penalty, even the executioners themselves.

“Ultimately, we are not talking about an issue,” he explains. “We are talking about people.” While the book relies heavily upon these “faces of grace,” Claiborne also takes up an array of biblical, historical, and sociological arguments.

Arsenal of Evidence

Early on, Claiborne engages familiar biblical texts to dispute the well-worn notion that the death penalty is God’s idea. Among his contentions: In the Bible, murderers like Cain, Moses, and David are not executed but spared. The Old Testament’s eye-for-eye standard of justice was not license for death, but a limit on retribution (Lev. 24:14–23). Further, Claiborne argues, Jesus applied a more rigorous limit on this “letter of the law” in the Sermon on the Mount (Matt. 5:38–39, 44). To Claiborne, the “sword” borne by rulers in Romans 13:4 is not the saber of a Roman executioner, but a small dagger worn on the belt. Most important, Christ’s death on behalf of fallen humanity lets mercy have the final word (James 2:13).

Claiborne also notes that the early church was united against state killing—not least because for 300 years, Christians were the ones under its blade. According to a third-century text called the Apostolic Tradition, Christians were forbidden from being executioners. Claiborne lets church fathers like Tertullian, Cyprian, and Origen raise their voices to defend the consensus conviction that “It is better to die than to kill.”

“Ultimately, we are not talking about an issue,” he explains. “We are talking about people.”

The book cites overwhelming sociological evidence. Claiborne writes, “One of the most powerful arguments against the death penalty is the simple fact of how disproportionately it is applied to race.” A black man is more likely to be executed than a white man, a poor man than a rich man. And a black, poor man in Texas—where more than half of America’s 2015 executions took place—is more likely than anyone to be sentenced to die. Practices like judicial override (where a judge can impose a death sentence even after a jury recommends a life sentence) and sentencing criteria like “future dangerousness” add to the problem of arbitrariness.

Perhaps most troubling is how many innocent men have been sent to die. Since 1976, about one of nine death row inmates has been exonerated, usually after languishing for decades in a cell. “Even if you believe that the death penalty is right in principle,” writes Claiborne, “knowing that innocent people are being sentenced and sometimes executed should give you pause. There is no redress once someone has been executed.”

This arsenal of evidence is impressive. But it doesn’t do enough to address the most powerful arguments for preserving the death penalty in some form. At times, Claiborne’s attempt to attach human faces to the death penalty makes his evidence appear overly anecdotal. And we learn too little about developments between Origen (“We must use the sword against no one”) to Martin Luther (“The hand that wields the sword is . . . no longer man’s hand but God’s”).

Executing Grace offers stories of restorative justice, where the goal is rehabilitation and reconciliation—not punishment.

Executing Grace offers stories of restorative justice, where the goal is rehabilitation and reconciliation—not punishment. But it’s fair to ask for examples beyond Rwanda and South Africa, where forgiveness of capital crimes was crucial to healing national wounds. What might restorative justice look like in an American murder case?

Claiborne denies that he sets grace and judgment, forgiveness and justice, against each other. But his vision for those essential j-words needs clearer focus. According to Claiborne, “The central concern of biblical justice was not ‘getting what you deserve.’ ” But the Bible upholds punishment—and not simply restoration—as an important dimension of justice.

From a biblical perspective, our rebellion against God makes us all capital offenders. To be sure, we need biblical language to delight in God’s willingness to judge Jesus and spare the repentant. But not all criminals will be rehabilitated. Like the killer Meursault in the Camus novel The Stranger, some will go to their state-sanctioned death without guilt or remorse. The Bible also gives reason for consolation, even hope, that when a sinner refuses mercy, God will avenge (Rom. 12:19).

As N. T. Wright explains in Surprised By Hope, God’s judgment is as much cause for celebration as his grace: “Faced with a world in rebellion, a world of exploitation and wickedness, a good God must be a God of judgment.”

Ethical Precision

Claiborne hopes the pro-life movement will oppose the death penalty as strongly as it opposes abortion and euthanasia. It’s debatable whether these issues belong in the same category. (Capital punishment, after all, raises questions of guilt that abortion doesn’t.) Either way, it’s clear that Christians must work for ethical precision in defining the value of human life.

For Claiborne, all killing is wrong because it hurts others as well as ourselves. In his words, “God hates sin, because God loves people and sin destroys us.” This is, of course, true. God’s commands are not matters of divine caprice: they point toward a way of life that protects human flourishing. But sin is about going against God’s will, even where it appears that no harm has resulted.

Claiborne hopes the pro-life movement will oppose the death penalty as strongly as it opposes abortion and euthanasia.

Forgetting this has consequences. In Canada, where I live, physician-assisted suicide was recently legalized on the theory that it prevents the harm of prolonged suffering. We might protest that facilitating suicide inflicts harm—but the person seeking death thinks the real harm comes in cruelly obstructing someone’s wish to die. To avoid this impasse, we must derive the value of human life from something beyond our desires and our pain.

Not everyone will share Claiborne’s “gut” instinct that there is something terribly wrong with executing serial killers and terrorists. Still, Executing Grace goes far in helping make Christ central to our conversation about the death penalty. As Claiborne pleads, we must “think and speak of Christ as one who was executed.”

Jen Pollock Michel is the author of Teach Us to Want: Longing, Ambition and the Life of Faith (InterVarsity Press).