Two unfathomable things happened, more quickly than almost anyone could have imagined, one year ago this June.

First, the terror: A young man named Dylann Roof, armed with a .45-caliber handgun, sat through almost an hour of the Wednesday night Bible study at Charleston, South Carolina’s venerable “Mother Emanuel” AME Church. Then he opened fire. Within minutes, nine—Depayne Middleton Doctor, Cynthia Hurd, Susie Jackson, Ethel Lance, Clementa Pinckney, Tywanza Sanders, Daniel Simmons, Sharonda Singleton, and Myra Thompson—were dead. Five survived. In an instant, wives lost husbands, fathers lost daughters, children lost parents, and a church lost its pastor.

Then, the mercy: Two days later, as the nation simmered with outrage and disbelief, the families of those murdered by Roof were allowed, in accordance with the law for bond hearings, to speak by closed-circuit television to Roof. Television networks carried the feed from both rooms: the room where Roof stood, nearly expressionless, flanked by police; and the room where his victims’ relatives were gathered. One after another, they spoke words of forgiveness even as their voices shook with grief and anger. Perhaps the baldest declaration of forgiveness came from Nadine Collier, daughter of slain member Ethel Lance:

I forgive you. You took something very precious away from me. I will never get to talk to her ever again—but I forgive you, and have mercy on your soul. . . . You hurt me. You hurt a lot of people. If God forgives you, I forgive you.

Of all the evidence in recent years that white supremacy remains imprinted on American life, the shootings were the most indisputable. A white boy had come of age in the 21st century drinking from the same poisoned spring as lynch mobs across the country in the 20th. He had stepped through loopholes in gun laws broad enough to allow a 21-year-old with a criminal history to purchase a Glock, and carried it into the sanctuary of a church in hopes of avenging imagined wrongs and inciting a race war.

At the same time, in a way without any obvious parallel in recent decades, the offers of forgiveness, prayers, and mercy in the face of judgment were an extraordinary public reminder of the holy power of the gospel of Jesus Christ, its persistence even in an increasingly secular nation, and its capacity to change hearts, minds—and legislatures. Within three weeks of the shooting, the debate about the Confederate flag flying over South Carolina’s State Capitol, a debate that had been entrenched in stalemate in the South Carolina House of Representatives, was over. On July 10, 2015, the flag was removed. As South Carolina Governor Nikki Haley noted, the grace shown on June 19 helped to change the minds of wavering officials.

All this happened in a few terrible and memorable days. And it all deserves to be remembered and commemorated, lamented and honored, as CT seeks to do with the following story.

But none of it is over.

Trauma and Grace

“I have not grieved yet,” said Shirrene Goss, whose brother, Tywanza Sanders, is numbered among the Emanuel 9. “It hasn’t been life as usual. When life still has to go on—what can you do?”

One year is nothing in the face of grief. Trauma can be inflicted in an instant, but it takes a lifetime—perhaps more—to be healed. The first debt owed to the survivors of the massacre at Mother Emanuel is to recognize the grief they still carry, and will carry for years to come. More deeply, to commemorate the one-year anniversary of Charleston requires seeing the ways that it simply re-inscribed the legacy of violence against Americans of African descent, a 300-year-old trauma that has not healed and oftentimes is not even acknowledged. The shootings in the basement of Mother Emanuel happened in an instant, but they recalled and perpetuated centuries of history—as, indeed, does the church itself, founded by African Americans and burned to the ground after Denmark Vesey’s slave revolt of 1822. To truly heal this most basic laceration in our body politic will likely take centuries more.

If the trauma inflicted in an instant will take a lifetime to heal, likewise, the questions that sprang up suddenly and insistently on June 17 can never be fully answered, and may forever haunt the Christian faith this side of the new creation. Where, exactly, was God—Emanuel, “God with us”—at the moment that Roof opened fire? In what sense is God “with us” in moments like these? What could possibly explain God’s terrifying patience with such evil? These are not abstract questions for the survivors, even as many of them continue to worship at Mother Emanuel and other churches in Charleston, pressing on to know and love the God who did not rescue their relatives and friends.

Then there is the unavoidable reality that this terror happened in a specific church—a historic congregation trying to make its way in the present, with ordinary human beings entrusted with sacred things, suddenly asked also to represent the endurance of African American Christians on a national stage. It is not surprising that in the aftermath of the shootings, fault lines already present grew wider and relationships that were strained ended up fractured. There is unfinished business within Mother Emanuel itself, as well as within the body of Christ in the city of Charleston. That business is only harder to address in the glare of public attention. And as other churches-turned-pilgrimage-sites—like 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham and Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta—can attest, that attention may never go away.

But while the trauma is not over, neither is the grace. Any forgiveness worth the name is a long obedience in the same direction. To extend forgiveness aloud is less to describe a finished reality than to commit to a personal journey—whether or not the offender ever joins you. And this is what many of the survivors of Charleston are extending, day after day, as they determine to forgive and to keep forgiving. In doing so, they bear more than their wounds. They also come bearing healing—as not just sufferers of God’s apparent absence but witnesses to God’s presence.

One year later, in company with the martyrs, the church in Charleston continues to sing the praises of the ever-present God. “There’s not a friend like the lowly Jesus—no, not one,” goes the hymn sung at Mother Emanuel one recent Sunday. If there is any God who can be said to be present at moments of great trauma, to empower forgiveness even of one’s most implacable enemies, it is surely this God, and only this: Jesus, the Lamb who was slain. Their Emanuel, and ours. —The Editors

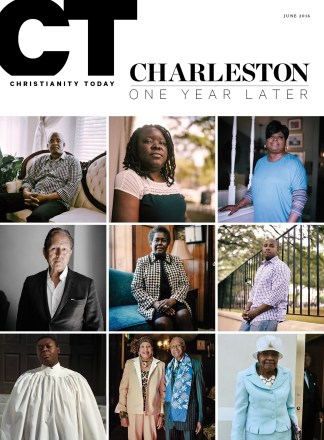

Anthony Thompson, husband of Myra Thompson

Anthony Thompson stands by his dining room table and hears his wife’s voice for the first time in months. From a digital recorder in his hand comes the sound of Myra Thompson’s first sermon, given at Emanuel AME Church during the 2014 Christmas season.

“The people walking in darkness have seen a great light,” she said, quoting from Isaiah. “There are so many storms in our lives. So much strife, anger, jealousy, disrespect. . . . These storms make it hard to find peace.

“Tell your storm to move, because Jesus is coming.”

As Anthony listens to the recording, Myra seems to be in the room with him. Her smiling face appears on the wall down the hallway of their modest brick home, not far from the now-iconic “Charleston Strong” mural painted after the shooting that took Myra’s life. On the dining room table is Myra’s Bible. The reading from Isaiah is still marked.

“She’s telling me to tell my storm to move,” he says.

Anthony, a retired probation officer and pastor at Holy Trinity Reformed Episcopal Church, had helped Myra prepare the Bible study she taught at Emanuel that fateful Wednesday night. They’d spent hours going over the text until she was satisfied.

As she left for church, Anthony remembers, she seemed to glow. She walked out the door before he’d said goodbye.

Myra was a schoolteacher, reading specialist, and, later, a school counselor.

“Everything she did was for somebody else,” he says.

When Anthony arrived at Emanuel after hearing the horrible news, the police wouldn’t let him inside the church. Because of the investigation, Thompson wasn’t able to see his wife’s body for another 10 days. Even today, he has a hard time believing she is gone.

“She was the boss,” he says, fiddling with his wedding ring as he tells of their life together. On their front lawn are neatly tended gardens and a pair of white rocking chairs. Inside, fresh flowers are set on the table every week; that’s what Myra wanted.

Their lives were busy with church, work, and raising Myra’s daughter, Denise, who called Anthony “Father.” In recent years, they took road trips to see Denise in Atlanta, spending hours on the drive down singing along to Motown hits.

On their most recent trip, Myra had taken Denise aside and described what she wanted for her funeral. It was as if she knew, says Anthony.

Anthony was one of the victims’ family members to speak at Roof’s bond hearing.

“We would like you to take this opportunity to repent,” the preacher told Roof. “Repent. Confess. Give your life to the one who matters most: Christ. So that he can change it.”

“I wasn’t planning on going,” says Anthony. “But God put it in my head. It was like he was speaking through me.” Afterward, Anthony felt peace. Today he doesn’t spend much time thinking about Roof or the trial.

“I pray for Dylann,” he says. “I pray every day that God will forgive him. That he will do what the Lord tells him to do—to repent and believe and live to tell about it.”

Nadine Collier, daughter of Ethel Lance

Nadine Collier misses her mother’s smile, so ebullient it was almost audible. It was the smile that greeted worshipers at Emanuel AME Church, where Ethel Lance was a lifelong member and an usher.

She even misses her mom’s love for caffeine-free Diet Coke. But not her biscuits, which were hard as rocks, says Collier (pronounced “Coyer”). “She could not bake,” she says, smiling.

The two talked every day, becoming close after Collier’s sister died in 2013. Losing her mother two years later means the grief weighs heavy.

Still, Collier’s faith remains strong. She drew global acclaim as the first family member to speak at Roof’s bond hearing.

“I forgive you,” she said. “You took something very precious away from me. I will never get to talk to her ever again. I will never be able to hold her again, but I forgive you, and have mercy on your soul. . . . If God forgives you, I forgive you.”

That’s what her mother would have wanted, says Collier. “I know she would have said, ‘That’s my baby. I taught her well.’ I would not have it any other way.”

In that moment, Collier says, she learned that forgiveness isn’t weak, a Christian duty done begrudgingly. Rather, “Forgiveness is power.”

She repeats that line on the hardest days. But healing is slow, given that Roof’s trial has now been delayed until at least January 2017.

“It’s like a setback,” she says. “You are trying to move forward, but it is pushing you back, because that part of your life is not closed. I still haven’t grieved yet.”

For much of the past year, Collier says, she has tried to process the loss without the community at Emanuel, where she grew up and sang in the choir.

The break from Emanuel started the first Sunday after the shooting.

“I thought they would shut it down, or be closed for a minute,” she says. “I was hurt. I felt disrespect. Not only for me but for everyone.”

The spectacle in the building where her mom had been murdered—swarming with out-of-town crowds and TV cameras—was too much.

Lance’s funeral was held at another church, in part because Collier could not return to Emanuel. She has been back once, on her mother’s birthday.

“Lord knows, that near killed me,” she says. “When I got in there, I tell you, I got so cold. I cried the whole time. It’s never going to be the same.”

Since then, Collier has worshiped at another church, whose name she prefers not to mention. There, she says, church members know what happened to her mom, but they don’t bring the shooting up every time she worships there.

There, she’s not Nadine from Emanuel. She’s Nadine.

Shirrene Goss, sister of Tywanza Sanders, niece of Susie Jackson

Among the family members of the Emanuel AME shooting victims, Shirrene Goss was hit especially hard. On June 17, 2015, she lost her brother, Tywanza Sanders, and her aunt, Susie Jackson. Her mother, Felicia Sanders, was also at the Bible study, but survived by diving to the ground with her granddaughter and playing dead.

Her mother “is a strong woman, much stronger than I would be,” says Goss, who attended Emanuel growing up and joined its Young People’s Department as a young adult. This past Lent, her mother and some friends re-read Rick Warren’s The Purpose-Driven Life together, as a way of grieving and preparing for the next chapter of their lives.

“It’s one thing to deal with the death of a loved one, but given the circumstances under which Tywanza died, it’s thrust us into a whole new world, dealing with media,” says Goss. She was among those who spoke at Tywanza’s and Susie’s joint funeral, attended by Governor Nikki Haley, Charleston Mayor Joe Riley, and the Reverend Jesse Jackson. Goss, 14 years older than her brother, recalled her nickname for him: “My Wanza.” “Now . . . seeing all the love that everyone had for him, he is not just ‘My Wanza,’ he’s ‘Our Wanza,’ ” she said.

Still, Goss says, she has not grieved yet. “When life has to go on—what can you do?” She stays busy raising her children and helping her parents. She was not at the bond hearing for Roof, but plans to be in the courtroom at his trial, set for January 2017.

“At this point, I can’t say I have forgiven. As a believer, I know that I have to.”

Betty Deas Clark, pastor, Emanuel AME Church

Worship began at Mother Emanuel a few minutes after 9:30 a.m. with a pronouncement from the back of the sanctuary. “The Lord is in his temple. Let all the world be glad!”

Like most Sundays since June 17, 2015, Emanuel’s pews were brimming with visitors—tourists, reporters, and attendees of a rally on gun violence taking place at the church that afternoon.

The visitors found their place among members dressed in their Sunday best: suitcoats for men, floral dresses and hats for women. Ushers, wearing white shirts and gloves, handed out bulletins.

At the front of the church, a floor-to-ceiling stained-glass window depicts two scenes from Jesus’ life: the Cross, where he is surrounded by two thieves and the weeping women; and the Ascension, where his arms are outstretched in blessing.

After the call to worship and a hymn, Betty Deas Clark—named Emanuel’s new pastor this January—invited worshipers to pray at the altar. Clark, a Charleston native, personally knew five of the nine victims.

As dozens filed forward, the church band played a calypso rendition of “There’s Not a Friend Like the Lowly Jesus”:

There’s not an hour that he is not near us. No, not one! No, not one! No night so dark, but his love can cheer us. No, not one! No, not one!

Jesus knows all about our struggles.

He will guide till the day is done.

There’s not a friend like the lowly Jesus.

No, not one! No, not one!

Later, worshipers paused to remember all those affected by the June 17 massacre, as a congregant read each victim’s name aloud. After the litany, family members stood while a traditional prayer attributed to Francis of Assisi was said for them: Lord, make me an instrument of your peace . . .

Clark’s tenure is marked by the call to be an instrument of God’s peace in a church marred by division over the past year.

Clark’s predecessor, interim pastor Norvell Goff, was praised for reopening the church the Sunday after the shooting. Worshiping, preached Goff, “sends a message to every demon on earth and in heaven: No weapon formed against us shall prosper.” Still, a number of victims’ family members say there were no calls, meals, or pastoral visits in that season of grief.

Clark is now tasked with helping to heal Emanuel AME’s wounds. To do so, she is drawing on the church’s past. Founded in 1816 amid the reign of slavery, Mother Emanuel has survived a burning, a ban against worship (during which members met underground), and an earthquake. Always it has been sustained by the liturgy, music, and preaching of the Word.

The Sunday CT visited, Clark returned to the pulpit in the afternoon for a rally on gun violence. The topic at hand: closing the so-called “Charleston loophole,” which allowed Roof to purchase the weapon he used on June 17. Roof’s criminal history should have disqualified him from buying the gun. But his background check wasn’t completed within three days, so the sale went forward.

At the rally, Clark drew from 2 Chronicles 6, where God tells Solomon how to respond when drought, pestilence, and swarms of locusts beset him. When tragedy befalls us, said Clark, the first step is to humble yourself, pray, and turn from your evil ways.

“How will God change Charleston?” preached Clark. “We cannot look for it on the outside. We have to look for it on the inside. We’ve got to change. We’ve got to put God first, and remember that the Earth is the Lord’s and the fullness thereof.”