When word of Prince’s death hit yesterday, what followed was a connected string of remembrances. Over and over, certain words and phrases reappeared: magical, immortal, supernatural. Like the death of David Bowie just a few months ago, Prince Roger Nelson’s death was shocking because most assumed he was already immortal. And yet, he is gone, at the age of 57.

Some will remember Prince mostly for his early work, when he roared into the music scene with raunchy, funky pop hits that featured a collision of funk, R&B, New Wave, and psychedelic rock. The disparate styles intermingled to create the monstrous sounds of Prince’s guitar and his roaring rhythm section. Prince himself danced and sang on top of the beast with a deft voice, howling and wailing and leaping into impossibly high falsetto. The essence of his sound—the power and the agility, the deep grooves and rock riffs, the rumble, that falsetto—never changed.

Neither did Prince’s sense of his own utter uniqueness. A friend in the music business once told me how bizarre a Prince show was for promoters. Everything backstage had to be painted purple, and the stagehands were explicitly told not to make eye contact with Prince. Someone who worked as an assistant engineer on a Prince record said that when Prince recorded vocals, he kicked everyone out of the studio, set up a mic over the mixing console, and recorded alone, with the lights off.

On Twitter yesterday, actor Albert Brooks recounted the one time he met Prince. “He was sitting elevated with literally 15 people at his feet. I said, “Which one is Prince?” No one laughs.” This story is quintessential Prince folklore. Majestic. Aloof. Nearly worshiped. (It is also quintessential Albert Brooks.)

Prince appeared to be an outlier, a magical person, a visitor from either a past or future where spirituality remained vibrant and mystery abounds.

He famously changed his name to a symbol for a while, forcing the media to refer to him as “the artist formerly known as Prince.” This move made him the butt of a thousand jokes on late-night television. Like much of what he did, it was about remaining elusive and refusing definition. He once sang, “I’m not a woman / I’m not a man / I’m something you will never understand.” Like Bowie, he wanted to defy our cultural categories and transcend them—to be something more than human.

Interestingly, that lyric comes from “I Would Die 4 U,” with its sexual-Messianic overtones. In a secularized world drained of spirituality, Prince appeared to be an outlier, a magical person, a visitor from either a past or future where spirituality remained vibrant and mystery abounds. His public persona was a curated effort at sustaining that sense of possibility. It’s no wonder his work featured sexuality so prominently: Sex is one of the few places that a secularized imagination maintains space for the possibility of transcendence.

In this, Prince was remarkably disciplined. His public life as a personality and an artist was performative through and through. Only in rare moments did a merely human Prince appear—like when Charlie Murphy told a story on Chappelle’s Show about playing basketball with Prince, which ended with Prince making pancakes for Murphy and his friends, or like Questlove’s story about Prince calling him in the middle of the night to go roller skating. (Though here, too, the magic prevails: Prince’s roller skates are apparently kept in an elaborate case, and they not only light up but emit showers of sparks as well.)

More Than a Weirdo in a Blouse

Twentieth-century philosopher Hannah Arendt once described public life in our day as performance and persona:

“Persona” . . . originally referred to the actor's mask that covered his individual “personal” face and indicated to the spectator the role and the part of the actor in the play. But in this mask, which was designed and determined by the play, there existed a broad opening at the place of the mouth through which the individual, undisguised voice of the actor could sound. It is from this sounding through that the word persona was derived: per-sonare, “to sound through,” is the verb of which persona, the mask, is the noun.

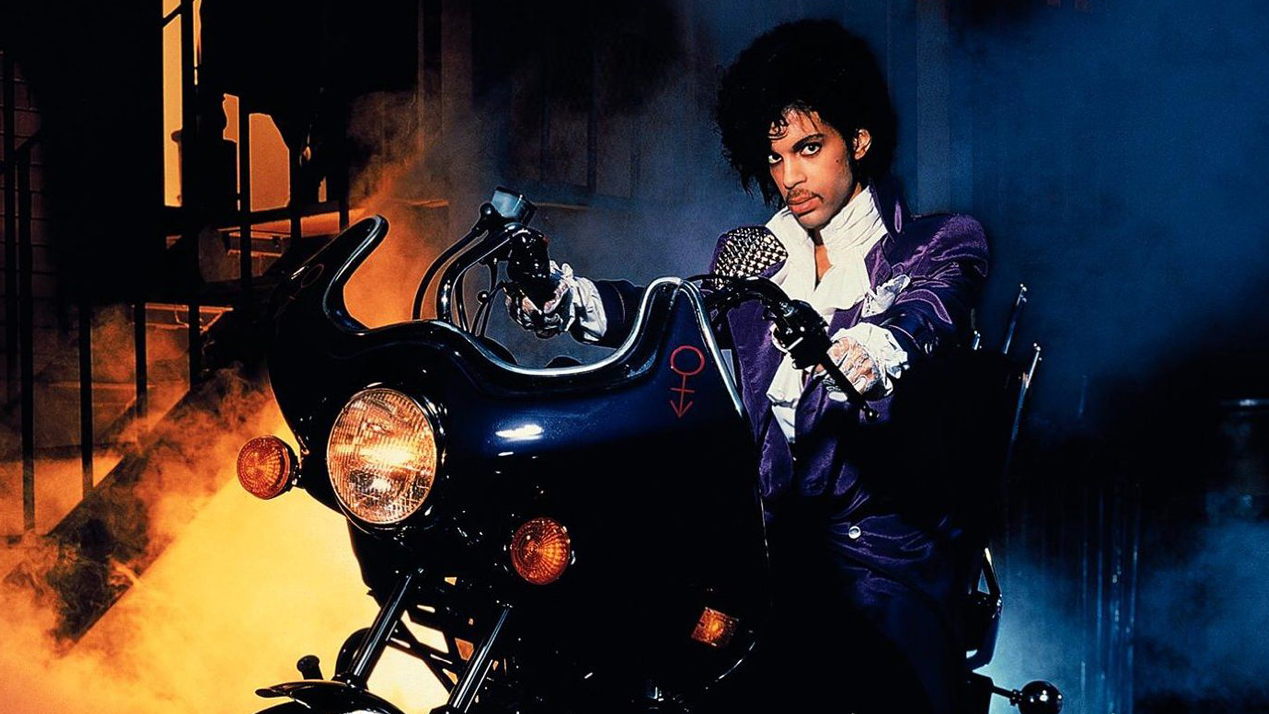

The celebrity we knew as Prince was almost certainly a Persona. What Prince Rogers Nelson was like may be known only by those closest to him, and to Nelson himself. For the rest of us, we know only the wonderfully eccentric, provocative Persona who appeared in Purple and Silk with a yellow Telecaster from time to time to “sound through” to the rest of us.

And sound through he did. It was the sounds he brought that made Prince so much more than a weirdo in a blouse. The music was a kind of guarantee on what the eccentricity promised. He looked like someone from another world or another dimension, and the intensity and clarity that came from his band—and especially from his guitar—confirmed our suspicions. Prince was the heir to Jimi Hendrix, only more potent, more furious, more clear and vigorous. He was at once graceful and violent, explosive and lyrical. His guitar moaned and howled and snarled like a rabid beast, layered in the fat germanium fuzz of his predecessor and in the shimmering delays and reverbs of his contemporaries. His tone was past and future. It was not merely the equipment; it was his hands that made the sound. It was singular. We will not hear it again.

There’s a famous clip, now being circulated, of Prince playing at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Steve Winwood, Jeff Lynne, and Tom Petty are playing “While My Guitar Gently Weeps,” along with Dhani Harrison (George’s son), when about halfway through, Prince joins the band to play the guitar solo. Prince is wearing a red top hat, and he takes over the front of the stage. Huge smiles appear as Prince plays. At one moment, he turns his back to the audience and drops backward toward the crowd. An enormous pair of hands appear, from nowhere, to catch him and prop him up as he leans his head skyward and continues to rip. Dhani smiles a big, wide, toothy grin. The solo goes on and on, with Prince finding new ways to attack it, new angles of approach, new melodic lines to unfold. When it ends, he flips the guitar off of his shoulders and throws it up to the heavens. You never see it come down. It’s as if, when Prince throws a guitar up in the air, it stays there.

I’ll also never forget his 2007 performance at the Super Bowl halftime. He took the stage in a downpour. The stage was slick, but no one slipped or stumbled. He tore through several of his hits, but he also covered Queen, Dylan, and the Foo Fighters (yes, the Foo Fighters) before ending with “Purple Rain.” The rain seemed to fall harder as he yelled out, “Can I play this guitar?” and tore into the kind of solo that for anyone else would have seemed self-indulgent. “Purple Rain” in the pouring rain. It was cinematic and perfect. One friend asked, “Do even the storms obey him?”

And yet, today, we know Prince was painfully, wonderfully, human. He canceled several recent shows due to illness. Yesterday, he was found unresponsive in an elevator at a recording studio in his hometown of Minneapolis. EMTs couldn’t revive him. He was human, and he is gone.

Prince’s life should remind us Christians of how truly wonderful it is to be human. He wasn’t actually more than human; but neither was he mere dust, or the product of a million cosmological accidents resulting temporary consciousness and animation. He was, instead, an image bearer, one who so clearly reflected the Creator’s own jaw-dropping creativity and power. The monstrous sounds Prince unleashed into the world came from hands that were fearfully and wonderfully made. He was a creature, as in a creation, and he lived a life that echoed the new-making work of God in the new-making work of his art.

Prince did not discover new notes; he made them new. He did not discover new instruments (the Telecaster is, after all, the original solid-body electric guitar); he made them new. He did not discover new sounds either—you’ll hardly hear a tone on his records that Jimi Hendrix didn’t make first—but still he made them new. Prince took the raw material of the created world around him and made it into something new, and when he sent that new thing back into the world, it made us smile, made us want to fall in love, made us want to dance. Today, especially, it makes us weep.

Mike Cosper is the founder and director of the Harbor Institute for Faith and Culture. He is the author of several books, including The Stories We Tell (Crossway) and the forthcoming The Quiet in the Chaos (InterVarsity Press).