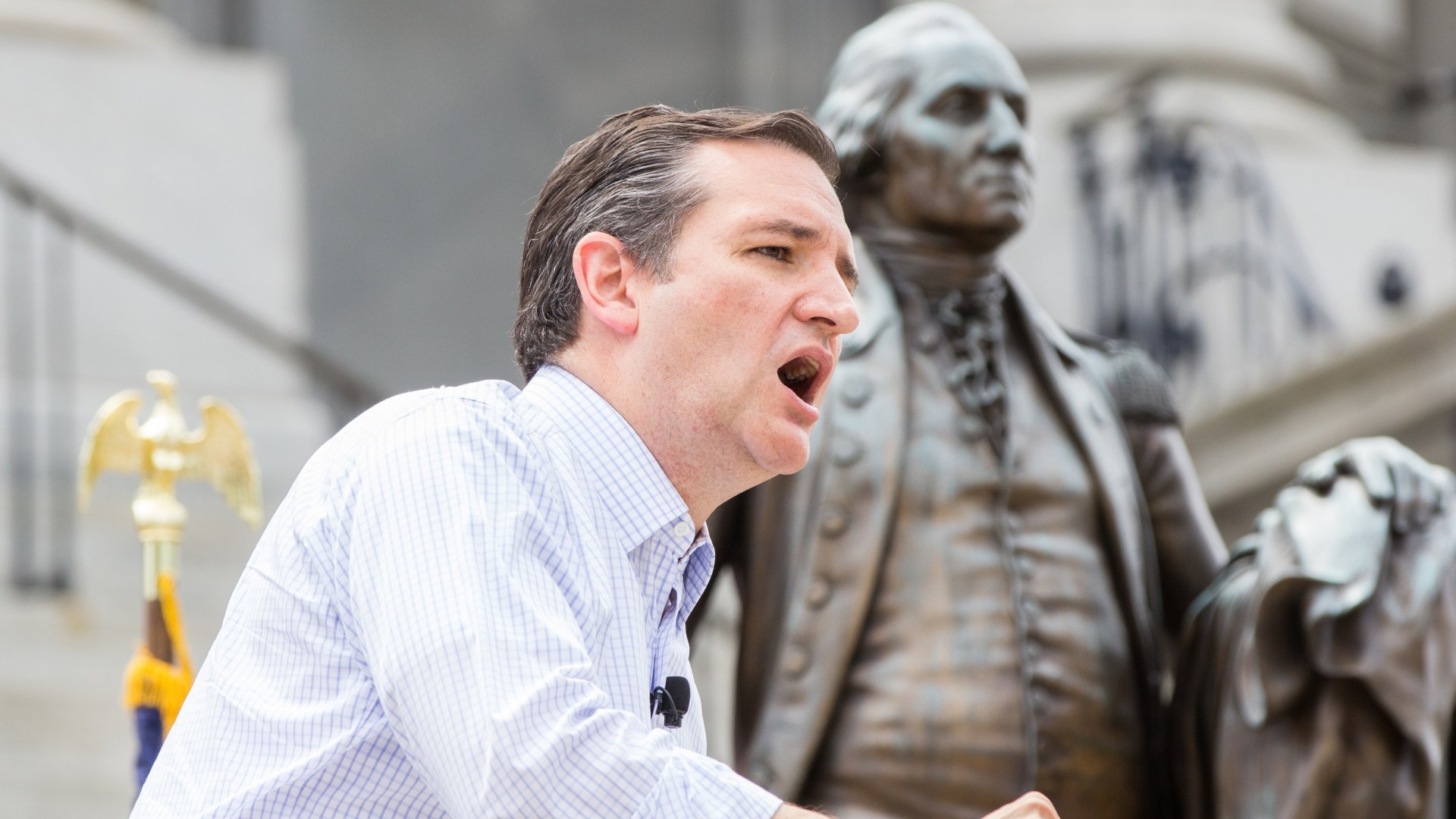

On the Sunday morning before this year’s South Carolina primary, Dr. Carl Broggi, the pastor of Community Bible Church in Beaufort, turned over his pulpit—emblazoned with the Protestant watchword “sola scriptura,” to GOP presidential candidate Ted Cruz. I am not sure if it is fair to call Cruz’s speech that morning a “sermon.” The candidate did not open up a biblical text and carefully explain its meaning in the way that I am sure Dr. Broggi had been trained to do at Dallas Theological Seminary and Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary.

Cruz did mention a few verses from the Bible during his message, but they were applied less to the spiritual lives of the souls in attendance that morning and more to the character of the United States of America as Cruz understands it. Let’s face it—this was a stump speech.

The Texas senator’s message was lifted from an old playbook. For nearly 400 years Americans have been conflating the message of the Bible with the fate of the country. Ever since the Puritan John Winthrop said that the Massachusetts Bay Colony was a “city on a hill” Americans have seen themselves as God’s chosen people—a new Israel with a special destiny.

Ted Cruz was raised in an evangelical subculture. He grew up studying the Bible and was taught to integrate faith and learning at Second Baptist School in Houston.

Cruz’s message on this Sunday morning was a product of the God-and-country narrative that took America by storm in the 1980s. This was an era when American evangelicals hitched their wagon to the Republican Party and set out to wage a culture war for the soul of America. Unlike any other candidate in the 2016 presidential race, Cruz has mastered the rhetoric first introduced by Jerry Falwell, Pat Robertson, and others on the Religious Right.

Cruz came of age—as a Christian and an American– during the height of the Religious Right’s power. During his sermon at Community Bible Church, he told an inspiring story of God’s work in his family. The personal testimony of Cruz’s father, Rafael, who is now an itinerant preacher and spiritual adviser to his son’s presidential campaign, demonstrates the power of the gospel to change the trajectory of a human life and reunite a family broken by alcohol abuse. Because God saved Rafael Cruz, Ted Cruz was raised in an evangelical subculture. He grew up studying the Bible and was taught to integrate faith and learning at Second Baptist School in Houston.

As the Cruz family assimilated to American evangelicalism, Rafael, a Cuban immigrant, also wanted to make sure that they assimilated the ideas and values he believed defined the United States. The precocious Ted went above and beyond the call of duty on this front. As a teenager, he memorized the United States Constitution and traveled around Texas reciting it at civic clubs and other patriotic gatherings as part of a group of like-minded kids known as the “Constitutional Corroborators.” His involvement with this group no doubt went a long way toward landing him a spot in the class of 1992 at Princeton University.

In short, there have been few presidential candidates in United States history with such bona fide God-and-country credentials.

Cruz’s Christian worldview is on display in virtually every speech he delivers. His campaign is perhaps best described as a reclamation project. He wants to “restore,” “return to,” or “reclaim” the “Judeo-Christian values” that he believes are “the foundation of this nation.”

This appeal to the past has multiple layers. First, Cruz believes that the United States was founded as a Christian nation. Though this belief has been contested by several historians—including many self-identified evangelical historians such as Mark Noll, George Marsden, Thomas Kidd, and myself—he continues to promote the idea, with the help of his super-PAC director and GOP activist David Barton, that the 18th-century founders created a nation that privileged Christianity. In some ways, Cruz’s entire campaign rests on this argument. If America was not founded as a Christian nation, the question is: What is there to restore, reclaim, or return to?

Cruz also wants to return to a time when Judeo-Christian values were more prevalent in American culture. Perhaps he has Dwight Eisenhower’s 1950s in mind—an era when there was prayer and Bible reading in schools and white middle-class Christian family values were the order of the day. Like his father Rafael, and like many culture warriors of the Religious Right, Cruz believes that Christians need to reclaim the various aspects of culture—the media, the entertainment industry, education, government—and take dominion over them. America was founded as a Christian nation, but over the years it has lost its way and needs to be restored. Such Christian restorationism, as historians such as Barry Hankins, Neil J. Young, and Daniel K. Williams have shown, was a vital part of the ideology that powered the birth of the Christian Right and continues to animate it today.

But when Cruz talks about restoring America, and encourages GOP voters to “remember who they are” as Americans, he is also referring to more recent history. During his speech in Beaufort, Cruz mentioned Winthrop’s idea of America as a “shining city on a hill.” For many evangelicals of a certain age, America as a “city on a hill” brings back memories of Ronald Reagan, the American president who energized the Religious Right. Reagan often used this phrase to describe the special destiny of the United States. It should not surprise us that he is a political hero to Cruz and many other evangelicals who look back nostalgically on the Reagan Revolution.

What are we to make of Cruz’s reclamation project? On one level, Christians, as citizens, should be concerned about the direction the country has taken. American culture—particularly in the entertainment industry—has become more coarse. Evangelicals concerned about the unborn or the Christian definition of marriage are being told that they are on the wrong side of history. Christian thinking is no longer acceptable as it once was in the academy.

Cruz is a master at fusing evangelical Christianity and presidential politics.

But many ask: Do we really want to go back? For example, one can probably make a better historical argument that the United States was built on the backs of slaves than on Judeo-Christian principles—a point that was not lost on a group of evangelical African American pastors from Cincinnati who met at Wheaton College in October 2013 to denounce the “let’s return America to its Christian roots” rhetoric that now pours forth from the Cruz campaign.

Cruz is a master at fusing evangelical Christianity and presidential politics. When he tells the men and women at Community Bible Church that “weeping may endure for a night, but joy comes in the morning” (Psalm 30:5), and promises them that “morning is coming,” it is unclear whether he is talking about God’s comfort in times of trial (as the psalmist intended) or Ronald Reagan’s famous “morning in America” campaign slogan. When he refers to the “great spiritual awakening” that he sees pervading the country, is this a revival meant to save souls or save America as a nation? Or is there even a difference to Cruz?

The Christian nationalism that defines the Cruz campaign is seen no clearer than in his defense of religious liberty. Evangelicals should cheer that someone like Cruz is responding strongly to legitimate threats to the free exercise clause of the First Amendment, especially as it applies to liberty of conscience in matters of contraception and same-sex marriage. These are serious issues. But Cruz understands the so-called “First Freedom” in a very limited way. When he talks about religious liberty, he refers almost entirely to the issues that conservative Christians face.

Cruz’s recently established “Religious Liberty Advisory Council” is made up entirely of conservative Christians who have a track record of caring very little about religious liberty as the American founding fathers defined it. For example, one of the most pressing religious liberty issues today is the right of Muslims to practice their faith without interference from the government. Even the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (Mormons) have defended Muslims after Donald Trump’s controversial remarks. So why does this committee say nothing about the religious liberty of Muslims?

Of course, if the United States is a Christian nation, and not a nation defined by religious liberty or what Marsden and others have described as “principled pluralism,” then Cruz’s approach makes perfect sense. Others would argue, of course, when one group’s religious liberty is in jeopardy, then everyone’s religious liberty is in jeopardy.

Finally, many evangelicals support Cruz based on his record of defending life. As he said at Community Bible Church: “Life is foundational. Every life, I believe, is a precious gift from God, and I look forward to the day when every life is protected from the moment of conception until natural death.” Amen.

Yet Cruz’s defense of life is hard to reconcile with his calls to carpet-bomb and “annihilate” ISIS. Carpet-bombing is usually associated with indiscriminate bombing that does not protect non-combatants or civilians. How does one reconcile the defense of human dignity, including the human dignity of our enemies, with these policy proposals?

There are no easy answers to this question or to many of the questions that the Cruz campaign raises. But they are questions that Christians concerned about bringing faith to bear on public policy need to be asking especially during this election season.

John Fea teaches American history at Messiah College in Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania. He is the author, most recently, of The Bible Cause: A History of the American Bible Society. He blogs daily at www.thewayofimprovement.com and can be found on Twitter @johnfea1.