Four years ago, my 32-year-old daughter, Christy, was found dead in her apartment, felled by a pulmonary embolism. She was with me a few days earlier, at my 60th birthday celebration, and no one could have imagined her impending death.

I have heard it said that after a crisis, you see the world differently. That is certainly true for my wife and me. Life is drastically altered when you go through every parent’s nightmare. Yet Christy’s death has also caused us to see the Word differently.

Sometime after her death, I read the Sermon on the Mount and was taken aback by these verses:

Which of you, if your son asks for bread, will give him a stone? Or if he asks for a fish, will give him a snake? If you, then, though you are evil, know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more will your Father in heaven give good gifts to those who ask him! (Matt. 7:9–11)

Previously, I had seen this text as a promise that God would give us good gifts if we simply ask in the manner that Jesus taught. But when Christy passed away, I suddenly saw another side of this truth: if a human parent would not give his child something dangerous, but only something good, how much more God the Father?

That may seem obvious to some, but I was reassured in a new way that God didn’t give my daughter a pulmonary embolism. He is not some selfish deity that “needed another angel in heaven,” as one person told me at the visitation before Christy’s funeral. God is working all things for the good of those who love him. But he is not the author of disease, decay, death, suffering, sin, and sorrow. He is love and the author of life—life abundant—and he even promises everlasting life. His plans for us are for good and not for harm, Scripture teaches.

This new way of thinking led me to re-evaluate other passages. One that resonated with me was Mark 5:21–43, where Jesus is revealed as a mighty miracle worker, one who overcomes the harmful effects of the Fall. The passage reveals far more than we’ve been taught to believe.

Moved by Compassion

The Gospel of Mark includes all sorts of miracle stories: exorcisms, the feeding of the 5,000, various healings, and, of course, a resurrection. In Mark 5:21–43, we encounter Jesus as both the healer and the raiser of the dead. Jesus did not perform these miracles to prove his divine identity, as some think, but rather to help others return to a normal way of life.

In this passage, Mark uses the “sandwich” technique: he begins one story (about Jairus and his dying daughter), then inserts a second (about a woman afflicted with a long-term ailment) before finishing the first. One reason for doing this is to provoke the reader to consider the relationship between the two stories, including their similarities and differences. In this segment, both stories are about women in distress. One is an older woman who has had an issue of blood for 12 years, and the other is a girl who had lived only as long as the woman had been bleeding.

Here, ritual uncleanness is a latent, but nonetheless striking, theme. Since women were considered unclean during their menstrual period, the older woman was presumably seen as continually unclean by those who knew about her problem. The girl dies during the course of this narrative, and her corpse would have been considered impure. In either case, Jesus is not concerned about contamination. His healing power not only negates, but also overcomes, both ritual impurity and the very causes of impurity. Not even death can stop him.

One intriguing feature in Mark is that Jesus’ miracles are always performed as intermittent acts of compassion. Jesus doesn’t put those mighty acts on his daily to-do list. He simply responds to the needs he encounters as he does what is integral to his mission: teaching and preaching (1:38). This is why he went from place to place, sharing the Good News. But when Jesus was confronted with a physical need, he stopped to heal.

What makes the story so intriguing is that Jesus, on the way to heal one woman, is delayed when he is confronted with the need of another. Apparently neither was part of his original plan for the day. And the first miracle, which causes the delay, makes the second one appear to arrive too late.

The emotion behind both stories is desperation—desperation in an age when medicine was a primitive art and often ineffective. People died of issues we in the 21st century could address with a trip to the drug store. But transcending the fear and peril and desperation is another key theme: faith.

The relationship between faith and healing is complex in the Gospels. Sometimes Jesus heals in response to the faith of a needy person. Sometimes he heals before they have faith. Sometimes he responds to the faith of people who bring an ill or injured person to him. Other times he heals even though faith is not mentioned. So while faith is not required for healing, there is a positive correlation between faith and healing. Faith seems to make a person more receptive to being healed. The opposite is seen in Mark 6:5–6, where the lack of faith—or, more accurately, willful disbelief—obstructs Jesus from healing in his hometown.

Notice that Jesus is not satisfied with just any kind of faith. Mark suggests that the woman thinks she can be healed by simply touching Jesus’ garment. But Jesus tells her that it was her faith in his ability to heal, not touching his robe, that rescued her. Her faith was elevated to a personal level.

Still, verse 30 presents one of the most intriguing details in all four Gospels. It suggests Jesus is a repository of healing power, which virtually oozes out of him toward those who turn to him with only a modicum of faith. While many in the crowd brushed up against Jesus, only one reached out to him in faith. But her faith was not the “name it and claim it” type. Some Christians today believe that if you simply believe sincerely or powerfully enough, you can ask anything of God, who is then obliged to dispense it. Such a view is false. If we ask for God to give us something that contradicts his will for our lives—or worse, his warnings about greed—we cannot make God an offer he can’t refuse. God is not a cosmic genie. But when it accords with his will, he does respond to faith.

Returning to Normal

But what of Jairus’s daughter, whom Jesus had originally set out to help? Tragically, she died while Jesus was delayed by the woman. I can only imagine how despondent Jairus and his wife must have become. A remedy for their daughter was close, but it seemed to have arrived minutes or hours too late. Yet when the tragic news comes to Jairus telling him not to bother Jesus any more since the girl has died, Jesus comforts and challenges him: “Don’t be afraid; just believe” (v. 36).

When Jesus arrives at the scene, he refers to the state of the girl as “asleep” (v. 39). Early Jews who believed in resurrection used “sleep” as a euphemism for death. To them, death was something you came back from refreshed and renewed. Further, when Jesus says she is not dead but asleep, some people laughed. This was probably the reaction not of cynical family members, but of hired mourners. It was common in Jesus’ day for families to pay others to mourn their dead and play sad music.

Notice that Jesus does not allow anyone into the room where the girl lies dead, except Peter, James, John, and the girl’s parents. What Jesus is about to do, he decides to do with only a select few present. He is not interested in wowing people into God’s kingdom. In fact, none of us can impress people unto salvation. Amazement is not the same as faith. And the Gospels frequently tell us that crowds were amazed at Jesus’ miracles, but that not all had faith in him. Believing leads to seeing, but seeing doesn’t always lead to believing.

We might think that texts like Mark 2:10–11 suggest miracles prove who Jesus is. There Jesus essentially says, “In order that you might believe the Son of Man has the power to forgive sins, I will help this man regain the ability to walk.” But the miracle is subsumed under a more important matter: believing that Jesus can forgive sins. It is not the physical miracle that proves who Jesus is. After all, Old Testament prophets like Elijah as well as the disciples performed miracles. In no way did their works suggest they were the Messiah. No, the focus of Jesus’ mission is announcing the good news about repentance, forgiveness, and everlasting life. Yet his miracles testify to his message.

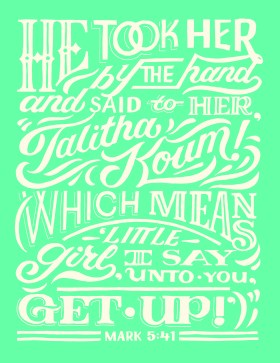

Once he went to the child, Jesus said, “Talitha koum!” (which means “Little girl, I say to you, get up!”)” Immediately, or as the King James Version says, “straightway,” she stood up and began to walk around, and Jesus instructed those present to give her some food. But he also gave them strict orders to tell no one what had happened (v. 43). Jesus was not concerned about acquiring a reputation. He simply wanted the little girl to get well and, as much as possible, return to normal life without becoming an object of gossip and gawking.

This highlights the theme of “messianic secrecy” that is so prevalent in Mark’s gospel. Jesus silences demons and humans, even the disciples, when they speak publicly about his identity. In some cases, Jesus does this so that he can define himself on his own terms, as the terms other people use are often inadequate. Sometimes Jesus doesn’t want recognition from a demon! Sometimes it is simply a matter of timing: Jesus has yet to disclose his identity in his own time and way. That’s why, I suspect, Jesus identified as the “Son of Man.” It didn’t fit the common language used in messianic speculations of that era. Jesus decidedly did not try to fit into people’s preconceived notions about who or what the Messiah should be. How often do we expect him to fit our expectations?

Waiting for the Resurrection

When I got the call that Christy had gone to be with the Lord, I had that sinking feeling you experience only when a loved one dies, the kind I imagine Jairus and his wife had when they learned of their daughter’s death. But it wasn’t just that I could now identify with Jairus. Jesus’ words to the little girl suddenly galvanized me. When people ask if I look forward to being in heaven with Christy when I die, I tell them that would be great and may very well happen, though we should remember that the Bible never promises family reunions in heaven. What I’m more excited about is the promise that Jesus will return to earth and raise the dead. The story of Jairus’s daughter points to something that we who have faith will someday experience.

On that day, I hope I hear Jesus say “Talitha koum!” to my Christy, so I can once again embrace and kiss her, showing her my love in a direct and tactile way. Most of the discussion about the afterlife in the New Testament is not about life in heaven; it’s about resurrection. It’s our destination, and it’s the final proof that, as Dylan Thomas once said, “Death shall have no dominion.”

Until that day, we live by faith, knowing that Christ is renewing all things, preparing us to return to the life that God originally intended for us.

Ben Witherington III is Amos Professor of New Testament for Doctoral Studies at Asbury Theological Seminary and author of Invitation to the New Testament: First Things (Oxford University Press).