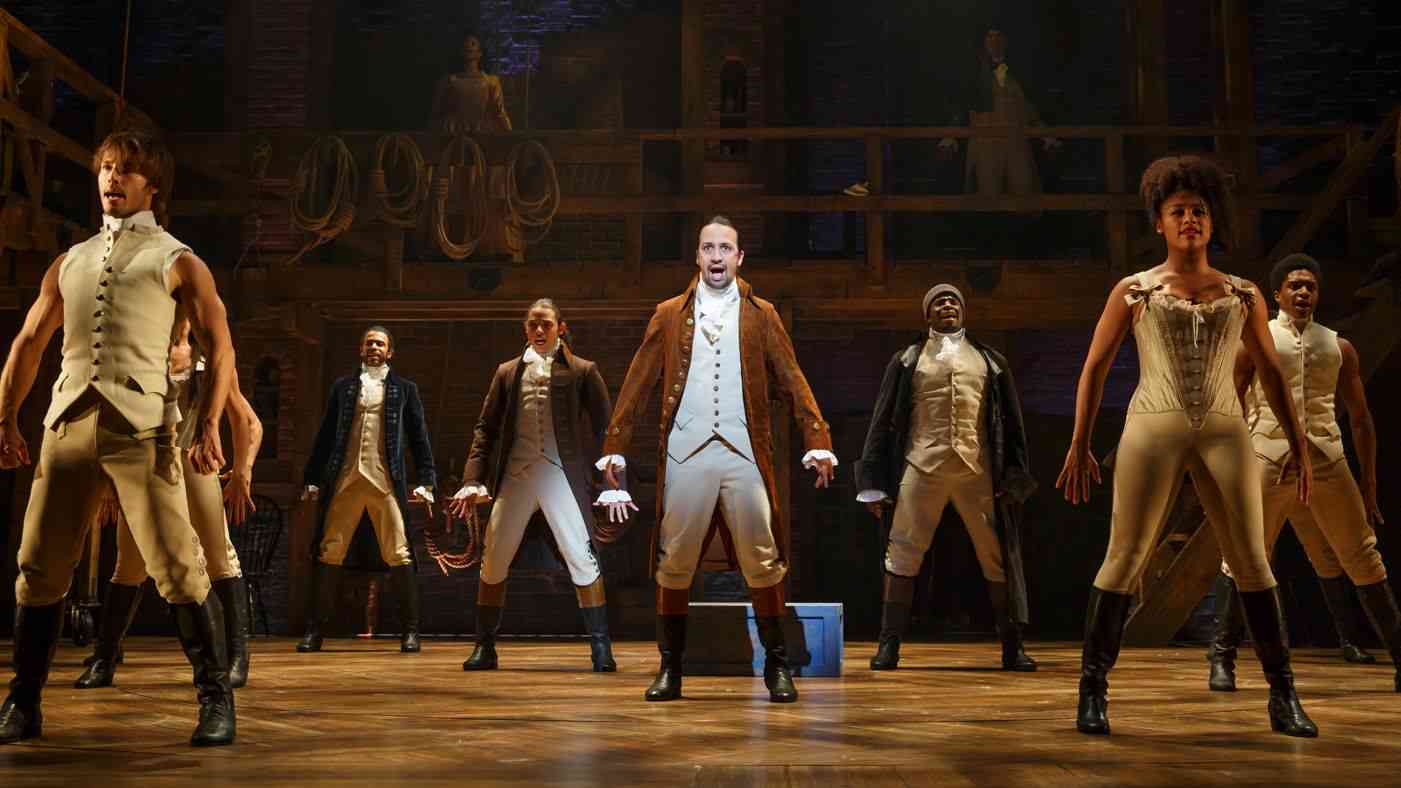

The hit Broadway musical Hamilton, written by and starring Lin-Manuel Miranda as the Founding Father whose face is on the $10 bill (for now), is rightly called the hottest ticket on Broadway and is making American history cool again. It’s a marvel of a musical, mixing genres from Broadway anthem to hip-hop, staging cabinet debates between Jefferson and Hamilton as rap battles, drawing parallels between rhetoric then and now, between contemporary political issues and those that faced the Founders.

It’s also highly literate, loaded with references to the Founding documents, the age of Enlightenment, Shakespeare, contemporary rap—and of course, the Bible.

I saw the show last month, but have been as obsessed with the Hamilton soundtrack (which you can listen to in its entirety) as anyone for a long time. (It’s a sung-through musical, in the manner of Les Miserables, which means if you’ve heard the album, you’ve basically heard the whole show, a couple of connective pieces notwithstanding.) The longer I listened, the more intentional quotations of and resonance with the Bible and a handful of Christian theological concepts I heard.

And I got interested. This display of biblical literacy is good for the show: it enriches both its sense of history—the Founders, whatever their individual beliefs, were conversant in the Bible—and in several cases builds out the story’s themes and characters in ways that make them even more complex and fascinating.

So I investigated, and here are the results: 18 times Hamilton directly references the Bible or Christian theological concepts, with short explanations, for any fan of the soundtrack or the show. I’ve ordered them by the order in which the tracks appear on the album. (And I hope I didn’t miss any.)

“Alexander Hamilton”

How does a bastard, orphan, son of a whore and a / Scotsman, dropped in the middle of a / Forgotten spot in the Caribbean by Providence / impoverished, in squalor / Grow up to be a hero and a scholar?

The show’s first track (watch the cast perform it at the White House a few weeks ago) introduces us to the characters and the early days of Hamilton’s life. These are the first five lines of the show, and they suggest, in a parlance favored at that time, that Hamilton’s place in history was fixed by “Providence”—or God. (For instance, William Bradford, the Plymouth governor who lived a century earlier, uses the term often in his writings.)

“My Shot”

Foes oppose us, we take an honest stand / We roll like Moses, claimin’ our promised land

This is an obvious reference: Moses led the Hebrews from slavery in Egypt to the land of Canaan, but they had to fight to take it. (Technically Moses never entered the Promised Land; that was left to Joshua.) The hymn “On Jordan’s Stormy Banks,” written by British Seventh Day Baptist minister Samuel Stennett, is contemporary with Hamilton’s setting—it was first published in 1787—and became popular in 19th-century America thanks to camp meetings.

But there are a lot more layers in here. The story of the Promised Land looms especially large in the imagination of both Civil War-era slaves longing for freedom and the Underground Railroad. “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” “Michael, Row the Boat Ashore,” and “Wade in the Water” are three of dozens of spirituals that use the imagery—which brilliantly managed to express a longing for freedom, call up Christian language to assuage those who would put down rebellion, and sometimes function as coded instructions for escape. The deep link to the Exodus story is also why Harriet Tubman was called “Grandma Moses.” The Civil Rights movement later drew on the same story, with Martin Luther King Jr. bringing it up repeatedly in his rhetoric; the movement revived many old spirituals as protest songs, as well as making oblique references to the Exodus in songs like “We Shall Not Be Moved” and “We Shall Overcome.”

Hamilton—which features an almost entirely non-white cast—frequently looks forward (and back, and to the present) and reminds us of those struggles, so this allusion is rich.

“A Winter’s Ball”

Watch this obnoxious, arrogant, loudmouth bother / Be seated on the right hand of the father

Aaron Burr (who acts as our de facto and annoyed narrator throughout the show) is describing Hamilton, who has just been appointed to be George Washington’s “right-hand man.” Washington is the “father of our country,” but this is a double reference: it’s the exact wording the Bible frequently uses to talk about where Jesus sits, interceding on behalf of mortals (Matthew 22:44; Acts 2:33, 7:55; Romans 8:34; Ephesians 1:20; Colossians 3:1; Hebrews 1:3, 8:1, 10:12, 12:2; 1 Peter 3:22, for starters). It’s such a frequent reference that the same phrasing appears in both the Nicene Creed and the Apostles’ Creed, which many Christian churches recite every Sunday as part of their liturgy.

“Wait for It”

My grandfather was a fire and brimstone preacher / but there are things that the homilies and hymns won’t teach ya

Love doesn’t discriminate / Between the sinners and the saints / it takes and it takes and it takes Death doesn’t discriminate / Between the sinners and the saints / it takes and it takes and it takes Life doesn’t discriminate / Between the sinners and the saints / it takes and it takes and it takes Hamilton doesn’t hesitate / He exhibits no restraint / He takes and he takes and he takes

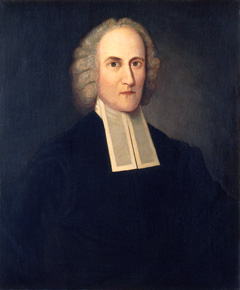

There’s a lot to unpack here. First of all, few people know (though many more know now) that Aaron Burr was the grandson of Jonathan Edwards, the “fire and brimstone preacher” who is most famous in American history for his sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” which appears in many anthologies of American literature. Edwards helped shape the First Great Awakening. Edwards's daughter Esther married Aaron Burr Sr., a founder of Princeton University. The Burr of Hamilton is their son, and a Princeton grad, too. (As Hamilton would have been if he hadn’t picked a fight with the bursar.)

This history plays a big part in the way the Burr of Hamilton speaks; a third of the show’s biblical references belong to him, because even though his parents died when he was two, their deep literacy and religious convictions towers over his memory.

So in a complicated bit of lyricism, “Wait for It” has Burr repeatedly mixing two separate references in his chorus. The “doesn’t discriminate / between the sinners and the saints” construction seems drawn, with a very high sense of irony on Miranda’s part, from Matthew 5:44-45: “But I tell you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, that you may be children of your Father in heaven. He causes his sun to rise on the evil and the good, and sends rain on the righteous and the unrighteous.”

The “takes and it takes and it takes” line plays with Job 1:21, in which the beleaguered Job says, “Naked I came from my mother’s womb, and naked I will depart. The Lord gave and the Lord has taken away.” Burr particularizes the force that takes things away from him over and over (“everyone who loves me has died,” he sings) as Death and Love and Life and, of course, Hamilton. This construction pops up again in his last big number, “The World Was Wide Enough,” when Burr tells us about his fatal duel with Hamilton, who in one sense stole his future from him even in death: “Death doesn’t discriminate / Between the sinners and the saints / it takes and it takes and it takes / History obliterates / In every picture it paints / It paints me and all my mistakes.”

(Sufjan Stevens also messed with this line in the last stanza of his song “Casimir Pulaski Day”: “All the glory when He took our place / But he took my shoulders and He shook my face / And He takes and He takes and He takes.”)

“Ten Duel Commandments”

The very title of the song needs no explanation, but there are two small lines in here that point up the generally accepted sense of an afterlife at the time: in No. 6, we’re instructed to “pray that heaven or hell lets you in,” and in No. 7, we’d better “confess your sins.”

“You’ll Be Back,” “What Comes Next,” “I Know Him”

Oceans rise, empires fall

King George has three scene-stealers in Hamilton, all of which paint him (in bouncy, ironic fashion) as a creepy controlling boyfriend who’s going to stalk you if you try to leave him. For a long time, I couldn’t figure out why I kept expecting him to sing “oceans rise, mountains fall” in the recurring chorus in each of his three numbers. Turns out this tiny little line echoes of Psalm 46:1-3: “God is our refuge and strength, an ever-present help in trouble. Therefore we will not fear, though the earth give way and the mountains fall into the heart of the sea, though its waters roar and foam and the mountains quake with their surging.” Appropriately enough, since he’s talking about turbulence and the staying power (he hopes) of his own empire. And for what it’s worth, a nearly-identical idea pops up in many modern songs sung in churches around the globe, including at least two by Hillsong: “Take Heart” and “Oceans (Where Feet May Fall).” The song “Shout to the Lord,” a ubiquitous presence in evangelical worship services when I was a teenager, phrases it as “mountains bow down and the seas will roar / at the sound of your name.” Same difference.

“Dear Theodosia”

You outshine the [morning] sun, my son

Hamilton was a religious man as well, and he read everything, including the Bible. Here he’s singing of his newborn son Philip, and borrowing from biblical suggestions that the glory of the Lord is brighter than the sun (Isaiah 60:9, for instance). Then there’s also the old gospel song that many kids learn in Sunday School, “Do Lord,” which contains the line “I’ve got a home in glory land that outshines the sun.” The song goes on to plead with the Lord to remember the singer “way beyond the blue,” a theme it shares with Hamilton’s interest in legacies, history, mortality, and memory. It was famously covered by Johnny Cash.

“What’d I Miss”

France is following us to revolution / There is no more status quo / But the sun comes up / And the world still spins

In another reference to the natural world, Thomas Jefferson arrives home with news of France’s impending revolution and invokes Ecclesiastes, in a likely effort to suggest that this isn’t apocalypse, it’s progress. This is a nutshell cipher for the whole show, which in part suggests that there is nothing new under the sun, and that every generation needs its own leaders, that young people learn the same lessons over and over again. The book of Ecclesiastes starts off with this proclamation and very similar language to the show: “Generations come and generations go, but the earth remains forever. The sun rises and the sun sets, and hurries back to where it rises. The wind blows to the south and turns to the north; round and round it goes, ever returning on its course . . . What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun . . . No one remembers the former generations, and even those yet to come will not be remembered by those who follow them” (1:4-6, 9, 11). As noted in “Alexander Hamilton,” for a long time America forgot Hamilton, too.

“Say No to This”

Lord, show me how to say no to this / I don’t know how to say no to this / Cuz the situation’s helpless / And her body’s screaming, “Hell, yes”

There aren’t any direct biblical references in this song, in which Hamilton succumbs to temptation in the form of Maria Reynolds (and pays dearly for it later)—then again, there are quite a few echoes of the stories of “folly” in Proverbs 9, which Hamilton would have done well to heed. But it’s worth noting that it’s actually a prayer for deliverance from temptation, no matter how delicious.

“The Room Where It Happens”

Burr: Now, Madison and Jefferson are merciless Hamilton: Well, hate the sin, love the sinner.

What Hamilton says here is so often repeated by well-meaning Christians that you might be tempted to think it’s from the Bible—but guess what! It’s not. (Though of course the spirit of it is all over the Bible, including the accounts in the gospels in which Jesus hung out with those whom polite society deemed unfit.) In the same song, Burr and the company also sing “In God We Trust,” which is on our currency but isn’t in the Bible either.

“Schuyler Defeated”

Your pride will be the death of us all. / Beware, it goeth before a fall.

This is Burr’s parting shot to Hamilton after the latter protests Burr’s unprincipled party-switching power-grab, and it’s a clever revision of Proverbs 16:18: “Pride goes before destruction, a haughty spirit before a fall.”

“One Last Time”

Like the scripture says: / “Everyone shall sit under their own vine and fig tree / And no one shall make them afraid.”/ They’ll be safe in the nation we’ve made / I want to sit under my own vine and fig tree / A moment alone in the shade / At home in this nation we’ve made / One last time.

George Washington was a deeply religious man, and after Hamilton protests at his plans to leave office, Washington relies on Micah 4:2-5—a passage about peace between nations—to explain his reasoning:

Many nations will come and say, 'Come, let us go up to the mountain of the Lord, to the temple of the God of Jacob. He will teach us his ways, so that we may walk in his paths.’ The law will go out from Zion, the word of the Lord from Jerusalem. He will judge between many peoples and will settle disputes for strong nations far and wide. They will beat their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning hooks. Nation will not take up sword against nation, nor will they train for war anymore. Everyone will sit under their own vine and under their own fig tree, and no one will make them afraid, for the Lord Almighty has spoken. All the nations may walk in the name of their gods, but we will walk in the name of the Lord our God for ever and ever.

“It’s Quiet Uptown”

I take the children to church on Sunday / A sign of the cross at the door / and I pray / that never used to happen before

As we noted here in CT last month, Hamilton was religious as a young man, less so for a long while, but then returned to his faith after the tragic death of his son Philip. The “sign of the cross” he refers to is employed by some Christian denominations, in which the forehead, chest, and shoulders are touched, often accompanied by the statement “In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost.” It serves as a reminder of the Trinity that isn’t just mental but also physical, inscribing the reminder onto our person again and again.

“Your Obedient Servant”

I am slow to anger / But I toe the line / As I reckon with the effects / Of your life on mine

Aaron Burr, again, calls in the Bible when his purposes aren’t altogether holy. God is called “slow to anger” a lot—see Psalm 103:8, for instance. And you can see the point, given that people are frequently awful, but the world is still spinning. Aaron Burr, less so.

“The World Was Wide Enough”

I catch a glimpse of the other side / Laurens leads a soldiers’ chorus on the other side / My son is on the other side / He’s with my mother on the other side / Washington is watching from the other side / . . . Eliza / My love, take your time / I’ll see you on the other side

The phrase “the other side” recurs throughout the show: Hamilton tells Burr in “The Story of Tonight” reprise that he’ll see him “on the other side of the war,” and tells Lafayette in “Yorktown” that he’ll “see you on the other side.” But he invokes the term most obviously, and with different implications, in the moments after he’s been shot and the world slows to bullet speed while his life flashes before his eyes. In this moment, he starts to see those who have passed away already—his friend John Laurens, his mother, his son Philip, George Washington. They’re on “the other side,” which is to say in heaven, and that’s where he’s headed, too, to finally take a break and wait for Eliza.

This wraps back to the “Promised Land” imagery in “My Shot,” the narrative of freedom taking on yet another layer in its resonance as both history and metaphor. The imagery in hymns like “On Jordan’s Stormy Banks” (“On Jordan’s stormy banks I stand and cast a wishful eye / on Canaan’s fair and happy land where my possessions lie / I am bound for the Promised Land”) are about a lot of things, including both freedom from slavery and oppression and freedom from the cares of life in this world altogether.

“Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Tells Your Story”

The Lord, in his kindness / He gives me what you always wanted / He gives me more time

In the final song, Eliza takes over from Burr as narrator, having inserted herself back into the narrative, and tells the audience of the 50 years that the Lord gave her to try and fulfill Hamilton’s life and her own. Equivalents of the “Lord in his kindness” phrasing are common in the Bible, with some translations using it exactly, and many writers and preachers in the English language since at least the 19th century have used it repeatedly. Eliza sees her half-century after Hamilton’s death as a kind gift from Providence with which to do good.

And here’s what you don’t get in the cast recording, the very last moment of the show: Eliza finishes singing, and then she looks up—and she gasps as she crosses to the other side.

Alissa Wilkinson is Christianity Today’s critic at large and an assistant professor of English and humanities at The King’s College in New York City. She is co-author, with Robert Joustra, of How to Survive the Apocalypse: Zombies, Cylons, Faith, and Politics at the End of the World (Eerdmans, May 2016). She tweets @alissamarie.