After Super Tuesday, many media reported that evangelicals came out strongly in support of Republican frontrunner Donald Trump. Indeed, those who self-identify as evangelical made up either a majority or plurality of the Republican-leaning electorate in every Super Tuesday state except Massachusetts. So it’s striking that, just as Trump has seemingly secured support from evangelicals, many evangelicals leaders are criticizing him and even vowing to abandon the “e word.”

This election year gives CT readers another chance to ask: What exactly is an evangelical? Is it about beliefs, or church attendance, or political leanings, or something else entirely? In the following essay, which appears in our April print issue, National Association of Evangelicals president Leith Anderson and LifeWay Research executive director Ed Stetzer have devised a timely way to answer these questions. —Katelyn Beaty, print managing editor

These days, everyone wants to know what evangelicals believe—especially about political issues.

Researchers have asked evangelicals what they think about same-sex marriage, science, the death penalty, immigration, and, especially, whom they plan to vote for in the upcoming election.

That’s understandable. Americans who identify as white evangelicals remain a powerful voting bloc in the United States—representing 1 out of every 5 voters in recent presidential elections, according to The Pew Research Center. And most—about 8 in 10—have voted Republican in at least one election. So it’s no surprise that Donald Trump recently proclaimed, “I am an evangelical.”

But who is an evangelical? Many pollsters and journalists assume that evangelicals are white, suburban, American, Southern, and Republican, when millions of self-identifying evangelicals fit none of these descriptions.

Many assume that evangelicals are white, suburban, American, Southern, and Republican, when millions fit none of these descriptions.

One of us (Leith) has led the National Association of Evangelicals (NAE) for a decade. The other (Ed) leads LifeWay Research, one of the largest Christian research groups in the world. We think there is a more coherent and consistent way to understand who evangelicals are—one based on what evangelicals believe.

Why It Matters

The desire to survey white evangelicals to determine their political interests inadvertently ends up conveying two ideas that are not true: that “evangelical” means “white” and that evangelicals are primarily defined by their politics.

But voting isn’t the only thing—or the main thing—that most evangelicals do. Politics are important, but politics aren’t our defining characteristic, nor should they be.

And clearly not all evangelicals fit the white evangelical category. Our country has become more diverse over the past half-century, and so have evangelical churches. To equate “evangelical” with “white evangelical” leaves out many people with evangelical beliefs.

“You never hear about black evangelicals,” Anthea Butler, associate professor of religion at the University of Pennsylvania, said last year. “Watch the 2016 election. When they talk about evangelicals again, they won’t go to Bible-believing black evangelicals. They’re going to talk to white people.”

Surveys that focus on white evangelicals shape the way our non-evangelical neighbors see evangelical believers. So they often perceive us primarily as political adversaries or allies, rather than people primarily motivated by beliefs.

As one unsympathetic political activist put it recently to Leith (without knowing he was president of the NAE), “All those evangelicals really scare me.”

But our new definition shows that when we examine them by what they actually believe, American evangelicals are quite diverse.

Researchers look at three factors when studying religious groups. Known as the three Bs, they are belief, behavior, and belonging. In order to understand any religious group, you have to consider all three.

Yet most public polling on evangelicals has focused only on belonging, asking people to identify with a specific faith tradition. In some cases, people are asked to identify themselves in basic categories like Catholic, Protestant, Jew, Muslim, and so on. Other polls ask people to use labels like “evangelical,” “born again,” or “fundamentalist.” (Pew, for example, combines “evangelical” and “born again.”)

More in-depth studies ask respondents the name of their denomination. Researchers then place those responses in a category using a standard set of historical traditions known as RELTRAD (short for religious traditions). For example, if you pick Episcopalian, you are mainline Protestant; if you pick Assemblies of God, you are evangelical.

Those traditions reflect most of the largest faith groups in the United States: evangelicals, mainline Protestants, black Protestants, Jews, and increasingly, Nones—those who claim no religious identity.

Denominational ties don’t always predict what someone actually believes.

Yet asking for religious self-identification isn’t enough. For example, many Christians hold evangelical beliefs but don’t call themselves evangelical; many Christians call themselves evangelical yet don’t hold evangelical beliefs. And denominational ties don’t always predict what someone actually believes. There are evangelical Episcopalians, for example, and Pentecostals who are more mainline in their theology.

Race and history are also important factors. A recent LifeWay study of evangelical beliefs found that only 1 in 4 African Americans who have evangelical beliefs self-identify as evangelical. That number jumps to about 6 in 10 for whites who hold evangelical beliefs and about 8 in 10 for Hispanic Americans who hold evangelical beliefs.

This study reveals a gap between belief and belonging. As a result, when pollsters refer to “evangelicals,” it usually represents a smaller, self-identified subset based on criteria that fail to take into account evangelical beliefs.

But if many individuals don’t use the label “evangelical” to describe themselves, is it fair to label them as such if their beliefs correspond with others who do use the evangelical label? Yes, for research purposes—to understand a group of Americans who hold something in common. For example, researchers typically do not rely on people to label themselves as young adults or older adults. The reason is that each respondent will have a different definition in mind. So researchers ask people their age and place them in a category.

Beyond Bebbington

Over the past few years, a group of evangelical leaders and researchers have worked on addressing the gap between belief and belonging. To do so, we developed a new research-driven definition of evangelical. The refined definition focuses on belief—rather than self-identification or belonging—and should help researchers understand evangelicals better.

Let’s start with some basics.

The refined definition focuses on belief—rather than self-identification or belonging.

The word evangelical comes from the Greek New Testament word euangelion; eu means “good” and angelion means “message.” Since evangelical means “people of good news,” all Christians are in some sense evangelical. But the term was eventually used to refer to Protestants in Europe and, later, a subgroup of Protestants in America.

Still, the Western religious movement that has become known as evangelical did not have a founding document or a single recognized founder. Instead, the movement has morphed over time, alongside several concurrent trends.

Evangelicalism is by nature a diverse movement. Though we affirm the historic creeds, there is no evangelical creed. We don’t all read the same books or sing the same songs. Neither do evangelicals agree on how to practice our faith; we disagree over who can preach, how to practice baptism and Communion, or whether we should drink alcohol.

Still, despite all the variety, our research suggests a common set of core beliefs. With early assistance from Ron Sellers, the mind behind Grey Matter Research, we began a two-year process of defining those beliefs through conference calls, meetings, and email exchanges.

At first the broad range of options started looking more like a sermon series than an elevator speech, a book rather than a business card. So we crafted a research definition rather than a theological creed, list of behaviors, or probe of church membership.

This new definition was influenced by the famed Bebbington Quadrilateral, developed by David Bebbington of the University of Stirling in Scotland. Bebbington argued that evangelicals in 18th- to early 20th-century England had four defining characteristics: biblicism, a love of God’s Word; crucicentrism, a focus on Christ’s atoning work on the cross; conversionism, the need for new life in Christ; and activism, the need to live out faith in action.

This has become a standard way to understand classic evangelical theological commitments in England and the United States.

These four characteristics were not meant to tell evangelicals what they ought to believe and how they should act. Instead, as Bebbington pointed out in a 2003 interview, they describe what evangelicals have believed and how they have acted.

“I’m a mere historian,” Bebbington said. “I simply look at evidence, conceptualize it, and write it up.”

Of course, some who identify as evangelical want to broaden, change, or repudiate one or more of these commitments—they want to change the understanding of what an evangelical is. But the changes being offered have yet to win a large consensus. Until they do, we thought it best to stick with a classic set of beliefs that have represented evangelicals for some time.

A group of leaders that included Richard Mouw of Fuller Theological Seminary, Paul Nyquist of Moody Bible Institute, and Mark Noll of the University of Notre Dame helped us turn those four characteristics into a list of 17 questions.

To ensure the questions asked would be helpful to future researchers, we field tested the questions, with the help of LifeWay and with input on the process from sociologists Rodney Stark at Baylor University, Christian Smith at the University of Notre Dame, Penny Marler of Samford University, Nancy Ammerman at Boston University, Mark Chaves at Duke University, Scott Thumma at the Hartford Institute for Religion Research, and Warren Bird of Leadership Network.

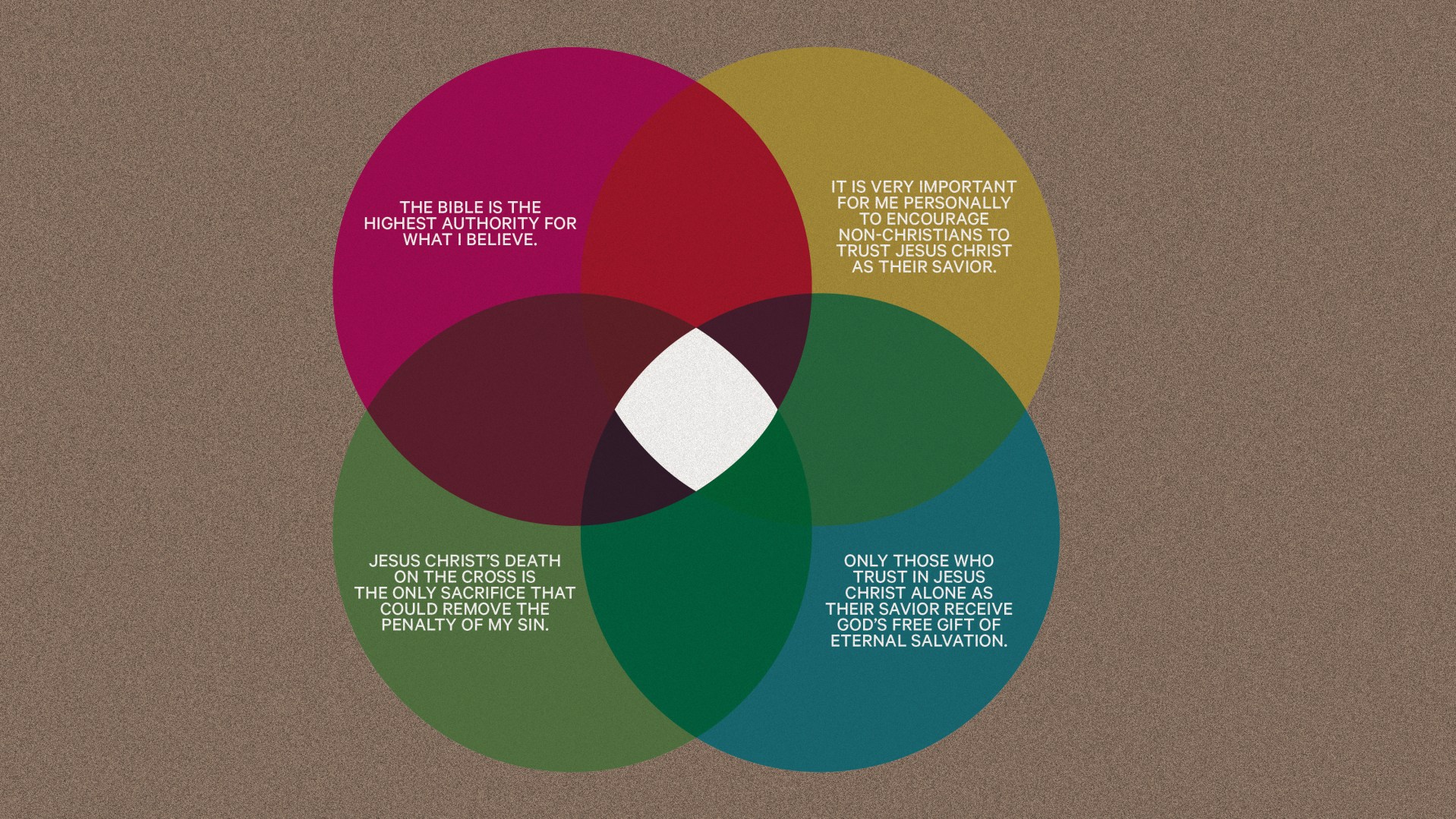

Our research suggests that, when it comes to statistical prediction, four belief statements in particular proved extremely helpful. We asked a representative sample of Americans whether they agree or disagree with the following statements:

The Bible is the highest authority for what I believe.

It is very important for me personally to encourage non-Christians to trust Jesus Christ as their Savior.

Jesus Christ’s death on the cross is the only sacrifice that could remove the penalty of my sin.

Only those who trust in Jesus Christ alone as their Savior receive God’s free gift of eternal salvation.

Those who agreed with all four statements were also likely to self-identify as evangelicals, thus bridging the gap between belief and belonging. They also attend church on a regular basis—meaning these four questions about belief also correlate with behavior (church attendance).

Though there are many other factors or belief statements many evangelicals would include here, these four, taken together, create a tool that predicts all the other things evangelicals could include.

Do these four questions bring some Christians into evangelicalism who might never call themselves evangelicals? Conversely, are there self-described evangelicals who will be excluded because they don’t strongly agree with every one? Yes and yes. That’s the case with every research tool.

Even so, the questions help us reliably identify which Americans hold classic evangelical beliefs.

Some evangelicals equate evangelical with “real Christian” or “orthodox Christian.” The tool does not determine the depth or sincerity of faith—only God can do that. It helps only to clarify which Americans hold these classic evangelical theological commitments.

When all is said and done, about 30 percent of all Americans have evangelical beliefs as described by the four questions. Broken out by ethnicity, 29 percent of whites, 44 percent of African Americans, 30 percent of Hispanics, and 17 percent of people from other ethnicities have evangelical beliefs.

But won’t adding one more definition only add to the confusion about the e word?

Not as long as we contextualize our definition. We can’t say, without qualification, that someone is an evangelical. We need to distinguish between a self-identified evangelical, a person affiliating with an evangelical denomination, or someone with classic evangelical beliefs. These describe evangelicals in different ways, and for the purpose of analysis, they create different subgroups of people.

But we trust that our definition will become a useful tool for researchers to more fully understand who evangelicals are. More important, we hope that as this tool is used, more Americans will see through the unfortunate cultural and political stereotypes and recognize evangelicals as a diverse people of faith who have given their lives to Jesus Christ as their Savior.

Leith Anderson is president of the National Association of Evangelicals in Washington, D.C.

Ed Stetzer is executive director of LifeWay Research in Nashville, Tennessee.